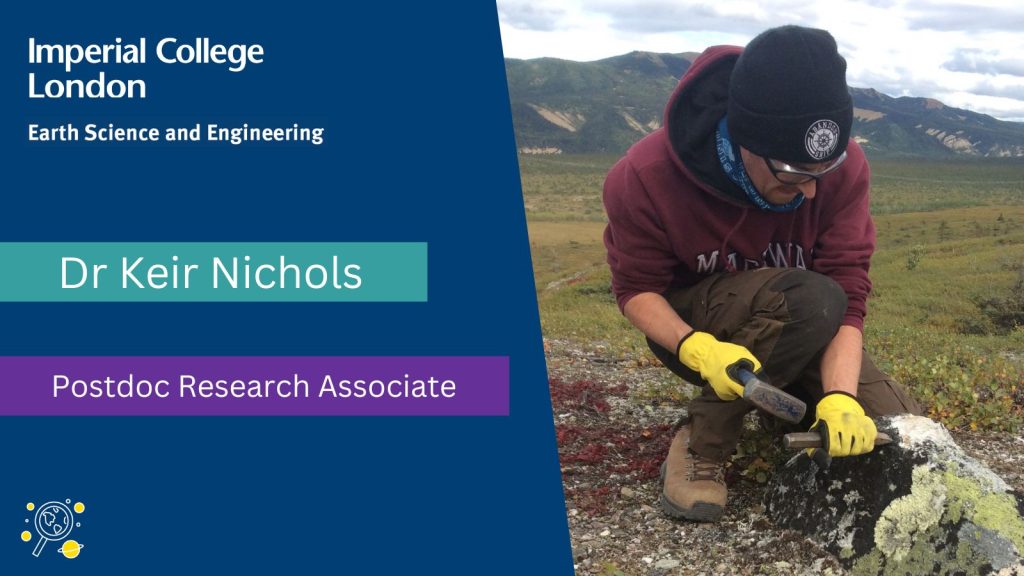

Dr Keir Nichols is a Postdoc Research Associate in the Department of Earth Science and Engineering (ESE) at Imperial. As a glacial geologist, he is interested in understanding how glaciers, particularly the Antarctic ice sheets, have changed over the last ~20,000 years.

By reconstructing the past, Keir is working to help reduce uncertainties in future sea level rise projections. In this blog post, Keir explains more about his motivations and what he is hoping to achieve with his research.

Describe your work in a tweet:

I measure isotopes in rocks to study the past of the Antarctic ice sheets.

Can you tell us more about your research area?

My research area is known as “glacial geology” and combines fields like palaeoclimate, geochemistry, and geochronology. It involves fieldwork in often quite remote places to collect samples from mountains next to glaciers and potentially hundreds of hours of lab work to measure the isotopes we are interested in. We measure isotopes that are only made in rocks when they are sitting at the surface of the Earth. In other words, the isotopes are not made when samples are covered by a glacier. This means that the amount of an isotope we measure in a rock tells us when a glacier thinned and uncovered that rock in the past. We can do this with multiple samples at multiple study sites to give us an idea of how the Antarctic ice sheets have changed in the past.

What research group are you part of?

I work within the CosmIC Lab group at Imperial, where we measure isotopes known as ‘cosmogenic nuclides’, which is where the lab gets the name from. As well as studying glaciers in different parts of the world (including Antarctica, Canada, and the US), during my time here students have also studied coastal cliff erosion rates and seismic hazards!

How do you see your research making an impact within and beyond academia?

This sort of research eventually feeds into things like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which ultimately helps governments prepare for the impacts of future changes in climate. The information on the past of ice sheets generated by our research is used to validate numerical ice sheet models that simulate the past of ice sheets before simulating their future (most importantly, how quickly they will melt and contribute to sea level rise). These studies projecting the future of the Antarctic ice sheets are then synthesised in IPCC reports, which means that this kind of research contributes, though indirectly, to this effort.

What drove you to your current area of research? Why excites you about it and why do you think it’s important?

Whenever I’m asked this question, I usually think back to one specific time whilst I was studying for my undergraduate degree, when I was very fortunate to spend a semester at the University Centre in Svalbard, Norway. After living in the Arctic for five months and learning about its likely bleak future in the face of a warming climate, I was left wanting to pursue a career that could contribute to better understanding how the fragile polar regions will change in the future. I’d also say my parents making sure I watched plenty of David Attenborough documentaries and taking me on childhood family holidays to beautiful, glaciated and formerly glaciated places like North Wales and the Alps helped!

Getting to plan and do fieldwork in very remote places that few people get the chance to visit is always exciting and something I feel very lucky to be able to do. I like to think that the way this research feeds into things like IPCC reports makes it important.

What has been your greatest academic achievement or career highlight so far?

This might sound cheesy, but I was very proud when an ESE MSci student I trained in the CosmIC lab for their MSci research was accepted to do a PhD at UCL! A less cheesy answer is probably when I found that a paper my PhD work contributed toward was cited in the latest IPCC report. Our research is a few degrees of separation from sea level rise projections, so it was a nice surprise to be cited in these reports that I’d studied since I was an undergrad.

What’s your favourite part of your job?

I absolutely love teaching students in the lab, it has been by far the most rewarding part of my job, both now and during my PhD. Saying that, I do value my time listening to music and working in the lab alone, too, so it’s a win-win. Spotify just told me in my Wrapped that I’m in the top 0.5 % of listeners worldwide. I’m not sure if that’s something to be proud of, but all of the lab work definitely contributes to that!

Who do you collaborate with at ESE, Imperial and elsewhere?

I’ve been lucky to contribute toward the research of an ESE MAGIC PhD student, look out for the paper coming out soon! The project my research is a small part of is a large collaboration with institutions that are mostly in the UK and USA, including the British Antarctic Survey, Colorado School of Mines, Berkeley Geochronology, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Northumbria University, and the University of Maine.

What makes you want to work at ESE and Imperial more generally?

The CosmIC Lab is one of the few labs in the UK that measure the isotopes that we use to study glaciers and ice sheets in this way. The reputation (and location) of the university and department means many earth scientists would think about working here!

What do you do to wind down?

On as many weekends as possible I like to go hiking, though I wish I lived closer to mountains! I also like to go to gigs as much as I can, which is one of my favourite things about living in London.

What are colleagues least likely to know about you?

It’s been a while since I’ve had to think of a cool fact about myself to give as an ice breaker, but I think having my appendix removed in the world’s northernmost hospital is pretty cool! They are also unlikely to know just how high Lana Del Rey was in my Spotify Wrapped.