by Sarah Hayes, PhD student in the School of Public Health

How can we maintain mans’ best friendship?

Here in the UK we think of dogs as mans’ best friend. But in some regions of the world they can be our deadliest enemy.

Meet Amos (name changed to protect identity).

He’s a 5-year-old boy living in rural Tanzania.

Ten days ago, he was bitten by a rabid dog.

Anyone exposed to rabies through a bite, scratch or lick from an infected animal must receive treatment immediately. A course of 3 vaccinations (known as post-exposure prophylaxis or ‘PEP’) will effectively protect a person from this deadly virus. But they must be given as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours of the bite. Once signs of disease develop there is no effective treatment and you’re condemned to a painful, distressing death.

Amos hasn’t had these vaccinations.

Why?

Because in rural Tanzania, access to healthcare can be extremely challenging. Sometimes it’s a lack of awareness of the risks that stops people seeking treatment. At other times it’s a lack of access to healthcare. In Amos’s case the nearest hospital able to provide PEP was over 2 hours away.

Transport costs alone can be prohibitive to some families. Add on the price of treatment and you begin to understand why an estimated 59,000 people a year(1) are still dying of this preventable disease.

So, how can we protect children like Amos?

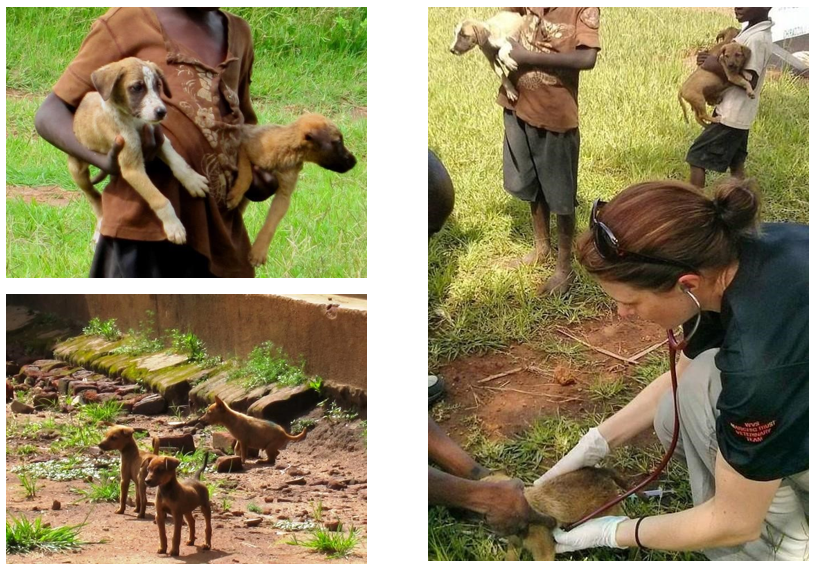

Vaccination of domestic dogs plays a key part. Whilst any mammal can be infected with rabies, domestic dogs are responsible for up to 99% of human rabies cases (2). If we reduce the level of rabies in dogs, we reduce the level in humans.

However, the benefits of dog vaccination campaigns can be compromised if rabies is circulating in other animals. Our research shows that in southern Tanzania where Amos lives, almost 50% of recently reported animal rabies cases have been in jackals. These jackals may have been infected by rabid dogs, but rabies could also be passing from jackal to jackal. Understanding the role that different species play in rabies transmission is vital in implementing effective control strategies. If rabies is being maintained in wildlife, vaccination of domestic dogs alone may not be enough.

Using a combination of ongoing surveillance, statistical analysis and mathematical modelling, my research is investigating the role of different species in rabies transmission in southern Tanzania. These techniques allow us to untangle the part each species is playing in virus transmission and to consider both the short- and long-term effectiveness of different control strategies. This is vital if we are to stamp out rabies from these communities and keep it out.

Thankfully, Amos did ultimately receive his vaccinations. But not everybody will be so lucky. Which is why it’s so important that we tackle rabies at its source and prevent people from being exposed in the first place. And if we can achieve this then who knows, maybe one day people the world over will be able to think of dogs as their best friends.

References

- Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(4).

- World Health Organization. WHO | Rabies. Who. 2017; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs099/en/