By Agnes Szwarczynska, PhD Researcher at Schroeder Lab at Silwood Park

Recently, I came across a Nature article titled “Reproducibility trial: 246 biologists get different results from the same data sets.” It got me thinking — what if Imperial students, with expertise spanning from animal communication to microbial science, took on the same challenge? That’s how The Living Planet Data Challenge was born — an exciting three-day event that, for the first time, brought together master’s and PhD students at Silwood Park to tackle a real-world data problem.

In the first week of February, participants applied their skills in data analysis, coding, and research to address a question at the intersection of ecology, evolution and environmental conservation. The primary aim of the challenge was to foster problem-solving skills in a fun and inclusive environment — free from the pressure of grades. But despite its playful nature, it turned into something students could proudly add to their CVs. It also provided a chance to practice presenting methodologies and refine communication skills ahead of thesis vivas. For me, it was a big lesson in leading an event and everything that comes with it — securing funding, managing logistics and fostering engagement.

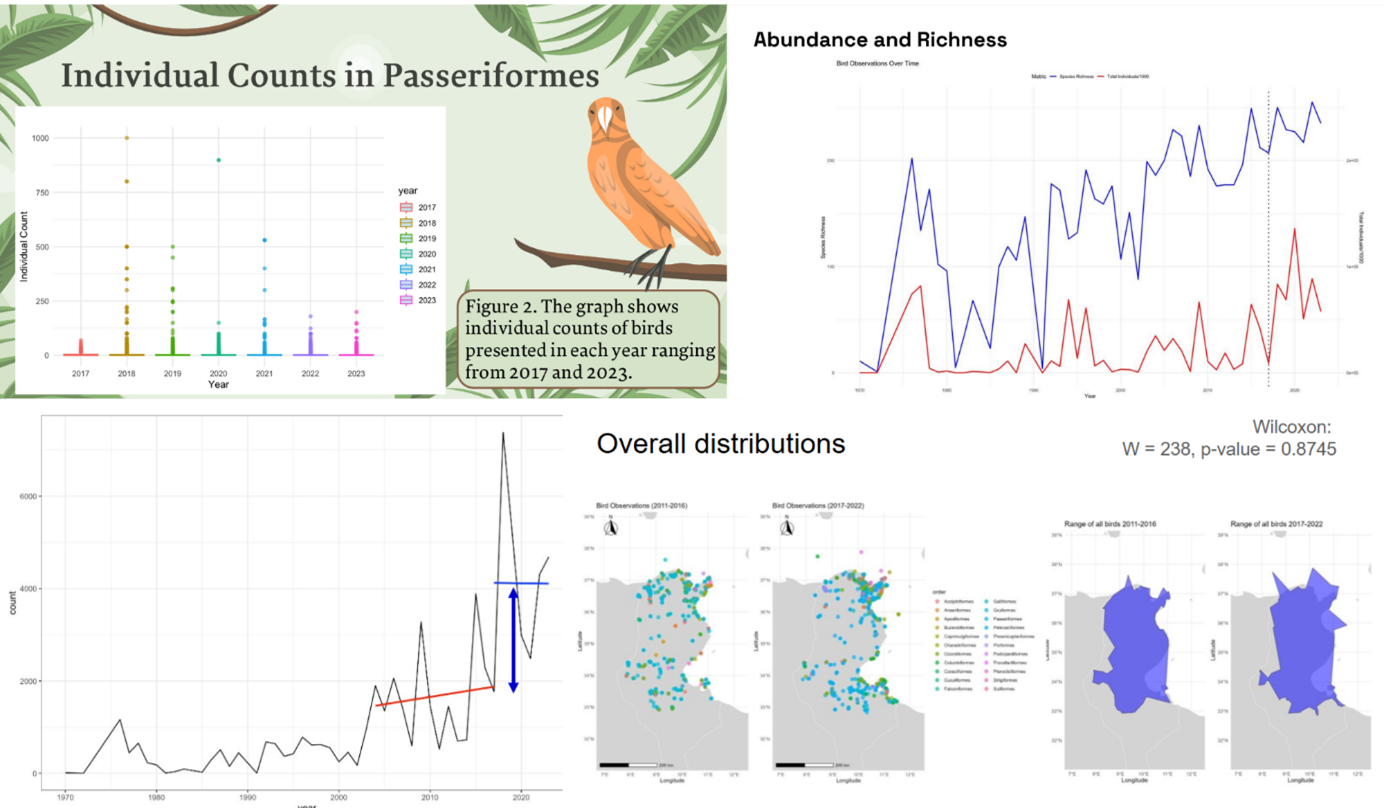

The event kicked off on Tuesday, February 4th, with participants tackling a problem using a publicly available dataset from eBird, a citizen science database with avian occurrence data. The challenge was set within a hypothetical scenario: as Tunisia’s newly appointed Environmental Officers, students had to assess whether the avian conservation program launched in 2017 had achieved its goals. AI tools were permitted, but participants had to justify their usage, adding an extra layer of challenge that required teams to critically evaluate their methodological choices.

[slides from the presentations of a) Jinxuan Cui, Xinting Cheng, Vicky Lin b) Yolanda Qian, Kotaro Kuroda, Rahim Dina c) Nathan Clark, Scott Tytheridge d) Saskia Pearce, Nia Potapova, Georgina Chow]

Using the eBird dataset, teams defined “success” in different ways — some focused on species diversity trends, while others analysed geographic distribution and changes in range sizes or simulated population numbers under various scenarios. From the organiser’s perspective, it was fascinating to see how different teams set out to solve the same problem by adopting very different strategies.

Over the next three days, five teams brainstormed ideas, analysed data and prepared their final presentations. Each day, they were provided with vegan and vegetarian snacks to fuel their creativity. More than just an academic exercise, the challenge served as a platform to refine scientific communication, encourage collaboration and knowledge exchange. With the two £150 prizes in vouchers for sustainable shops, teams were motivated to demonstrate that their approach was the most scientifically robust.

On the final day, teams presented their findings in 10-minute presentations, followed by a Q&A session with a panel of postdoctoral researchers. The prize in the master’s students category was awarded to Saskia Pearce, Nia Potapova and Georgina Chow for their ability to create a well-structured, compelling story and its critical interpretation. In the PhD category, the prize went to Nathan Clark and Scott Tytheridge for accounting for data collection biases and conducting a robust analysis that considered both the short- and long-term effects of the intervention.

Here, I want to thank all the teams for their hard work and determination! Special thanks to Dr. Ambre Salis, Dr. Vivienne Comyn-Platt and Dr. Balig Panossian for assessing the presentations and providing detailed feedback and to Stanislav Modrak for help with the event organisation. Lastly, this event would not have been possible without the funding provided by Imperial’s Early Career Researcher Institute, whose support brought the Living Planet Data Challenge to life.