A post by Professor Chris Hankin, Director ISST

Increasing digitization has led to convergence between IT (Information Technology) used in offices and mobile devices, and OT (Operational Technology) that controls devices used in critical infrastructure and industrial control systems. The IoT (Internet of Things) is also rapidly growing, with around 10 billion devices today.

These trends raise concerns about the interaction between safety and security. The reality of the threat has been highlighted in national news coverage, from cyber security vulnerabilities being exploited to compromise vehicle safety, to denial of service attacks launched from consumer devices.

Discussions are sometimes hampered by the lack of clear definitions of the concepts. Safety is often understood as concerning protection against accidents, whilst security is about protecting systems against the action of malicious actors. But these two definitions miss some essential aspects of the two concepts. A slightly different view is that safety is about protecting the environment from the system and security is about protecting the system from the environment.

Another contrast between the two concepts is how we approach risk assessment. Safety often considers the risk to life and limb and measures risk using actuarial tables. Security more often measures risk through consideration of the threat to information assets – at the moment data breach may be the key concern. As cyber physical systems become more prevalent there must be a convergence between these different approaches.

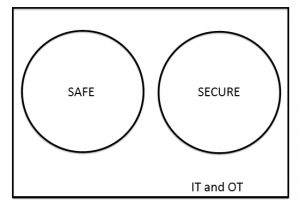

From a regulatory and standards point of view, the following Venn diagram summarises the current situation:

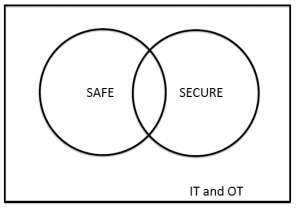

However, practitioners recognize that there is not a clear separation (indeed it would be undesireable if there was), so the following is a better diagram of the current situation:

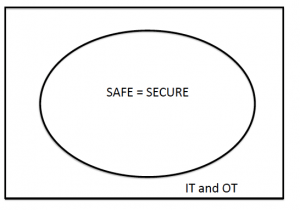

New standards are beginning to consider both safety and security. There is then a question about how large the intersection should be. There appears to be general agreement that the following diagram is wrong:

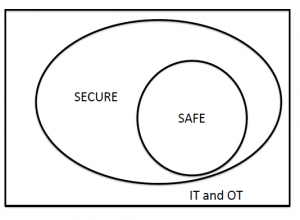

There are differences between the two concepts and we have hinted at what those might be. However, some commentators, predominantly from the security sector, have questioned whether a system can be safe if it is insecure.

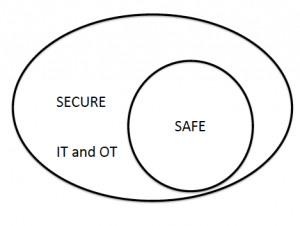

The examples of compromise to vehicle safety mentioned earlier give some weight to this view – it is clear that physical harm can result from the exploitation of cyber vulnerabilities. So maybe the following diagram is a better representation:

This is not universally accepted – some would argue that insecure components can be deployed in a system without compromising the safety because of the way in which those components are deployed and their effect is constrained.

Of course an alternative diagram would represent the secure systems as a subset of the safe ones – this could be verbalized by a slogan that a system cannot be secure if it is not safe. This is clearly wrong; safety, in the way we have viewed it here, is only really an issue for OT systems but we clearly want our IT systems to be secure.

For the future, we might want to re-think the relationship between safety and security. The UK Cyber Security Strategy 2016-2021, published on 1st November 2016, is based on three strands – Defend, Deter, and Develop – underpinned by international collaboration. The Defend strand talks a lot about “secure by default” systems and this could be an argument for breaking “out of the box”:

I am sure that this is a debate that will continue for some time.

Chris Hankin

Chris Hankin is Director of the Institute for Security Science and Technology and a Professor of Computing Science. His research is in cyber security, data analytics and semantics-based program analysis.