On 3 May, we hosted the first arts workshop for the Triptych of Science arts initiative, which brings together people working in scientific research culture to create art about their experiences in science at Imperial. The idea of the ‘Tryptich’, a tripartite art piece, is to explore three themes that might not be involved in the typical narratives of research culture, but that tend to surface in any conversation with people working in research: Time, Emotion and Balance.

As the curator in residence, I was tasked with thinking about building an exhibition, the “end-product” of this project. Yet I found myself observing what happens when researchers come together to make art, fascinated by watching the process unfold. If I had to choose one word to describe what this workshop was about, for me, it would be ‘forms’.

As people trickled into the room, they were greeted not by the typical set of classroom tables, but by a single large one formed of several pushed together. On this banquet table was a feast of art materials: string, paper, clay, glue, thread, ink. And of course, some plastic covers to anticipate (and encourage) mess.

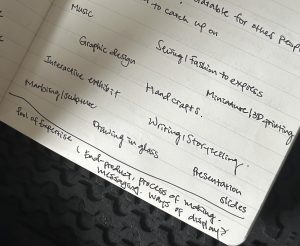

Once everyone found their seats, introductions began: we shared our occupations, research or professional focus, and perhaps most importantly, any experience with art. To my surprise, there was hardly any repetition; almost everyone mentioned a different creative form.

Some participants brought in examples of things they had made: the yellow jacket they were wearing, a cute fluffy dog, an egg of glass filled with purple swirls; paper marbling in bright cellular shapes; an exquisite miniature landscape, featuring a bloodthirsty bunny rabbit nestled among tiny rocks and flowers. We also heard about many examples of participants combining science and art, for instance, a piece of music encoded in DNA, with simulated evolution to mutate the melody over time.

Discussions of science became quite detailed, but these cheerful chats about genetics and material science seemed different around a multidisciplinary table than they might within a laboratory. The knowledge exchange was more social than goal-oriented – not done to build an argument or make conclusions, but simply to share without judgement. This became clear when someone expressed hesitancy about being entirely new to art making. The others soon reassured them that the experience they bring is just as valuable in the context of this project, as a collective initiative of learning and unlearning, art making and thinking about research culture.

A theme emerged that we should not focus simply on making the final product for the installation, but that we should also display evidence of the process. We decided to keep an archive of drafts, notes, sketches, and reflections as equally important to the final art piece.

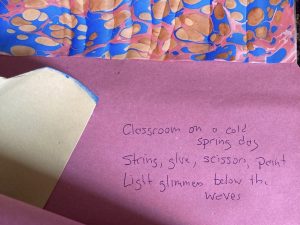

Then, our artist-in-residence, Ella Miodownik, facilitated the main activity of the day: to make ‘bad’ art. The word ‘bad’ was used to encourage a letting go of judgement and end-products; to not focus on trying to make something good, but just to play around and enjoy the making process. Each person was directed to take a piece of paper and do something to it for five minutes – to manipulate it in some way, whether cutting, folding, or ripping. Drawing or writing was implicitly discouraged due to a lack of any writing utensils on the table – but our own project leader, Stephen Webster, broke this rule, procuring a biro from his pocket and composing a short poem, hidden in a fold of his paper.

The craft session therefore began with the very important and serious process of picking out one’s favourite colours of paper and soon, everyone was immersed in making. People were sneaking peeks of what others were doing out of pure curiosity, but were mostly dedicated to their own ideas. And so began a period of comfortable silence, interrupted only by quiet requests to pass the scissors.

Somehow the five minutes I had planned for the activity turned into an hour, with all of us quietly absorbed in art-making – even Mikayla scribbling away and Madisson filming the process were totally immersed in their own quiet practice. It felt like a reversion to childhood and was supremely calming to my nervous system. Being together, and making-with… I think we might have accidentally done some kind of art therapy. (Ella)

Once again, no two forms were the same. Some chose to let their paper remain flattened and experiment with embroidery, cutting and weaving; others created shapes, structures and texture out of the paper. We even explored interactivity – one participant ripped and folded their paper into a perfect cone, before allowing the audience (which was just us, for now!) to unfold the piece in a performance artwork. Ella appealed to my curatorial perspective by hanging her piece from the ceiling, showing how the concept of ‘all forms’ is not just about the piece of work, but also about how the work is displayed. People gradually started to stand up, walk around and talk about each other’s art. Small and sweet conversations were humming in the room.

There was an interesting conversation about handcraft, where we discussed how distinctions between what is considered ‘fine art’ and ‘arts and crafts’ often correlate with hierarchies of gender and class. We resolved that this project would reject this distinction, embrace all forms of art as equal, and celebrate undervalued art forms such as textile.

This led nicely to Ella’s announcement of what our final art form would be: A multimedia quilt!

What is a quilt? In a sense, it is a constraint, but one that allows for creativity. It is made up of units, or quilt squares, but each one is different. This gives us options: We could each make our own quilt square, collaborate with someone on a square, or make a square all together. Then we can bring it all together at the end. This way, we can participate in a mix of co-creation and individual or asynchronous working. (Ella)

Participants discussed the idea of creating a collective piece where they could still have the capacity to be imaginative and create their own works. Ideas started to bloom: using materials from the lab, integrating journals and other aspects of daily scientific life, mapping and graphing out emotions or time spent doing science, and how they might want people who come to see the exhibition to engage with the quilt.

All of it will contribute to the multidimensional quilt – paper, string, marbling, clay, writing, video, data collection, narrative, performance. The focus on process, co-creation, multiple media – moving forward these ideas will be central to the project. The ideas of our Tryptich of time, emotion, and balance, will still be simmering there, directly relevant to some quilt “squares’ and more tangential to others. (Ella)

Although some people slowly began to leave and return to the hustle and bustle of their lives, conversations ranging from handcraft to chemistry lingered in the room for another hour. One of our participants brought their marbling materials to the session and gave a brilliant impromptu workshop on the technique, guiding us to create bright abstract prints while explaining the science of surface tension. More importantly, we started to see people making connections, comparing and exchanging their inspiration, and forming a sense of belonging as a group of artists in its early days.

It’s not too late to join the group of scientist-artists and contribute to our tryptich-quilt of research culture! The next session will be held on Wednesday 19th June 12-2pm. Reach out to Stephen Webster (stephen.webster@imperial.ac.uk) if you are interested.