Lung function predicts cardiometabolic diseases

We wanted to see if how well we breathe is connected to serious illnesses like diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. To figure this out, we studied almost 6,000 people from 15 countries over 10 years. These people were participants in the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study. We focused on something called “lung function,” which is a measure of how much air we can breathe in and out.

We found that people who could breathe out more air were less likely to get diabetes, heart disease and stroke later in life. On the other hand, people with smaller lungs or lower lung function had a higher chance of getting these conditions. This means lung health is super important, not only for breathing but also for staying healthy in other ways.

This finding may one day help doctors predict who might be at risk for serious cardiovascular and metabolic health problems in the future. It would be great if lung function tests could be added to regular health check-ups to catch problems early.

In short, taking care of our lungs might help us avoid not just breathing problems but other illnesses too! So it’s yet another reason to stay active, avoid smoking, and breathe in that fresh air when you can.

Check out the manuscript that has been published in BMJ Open Respiratory Research and is available in open access here: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2024-002442.

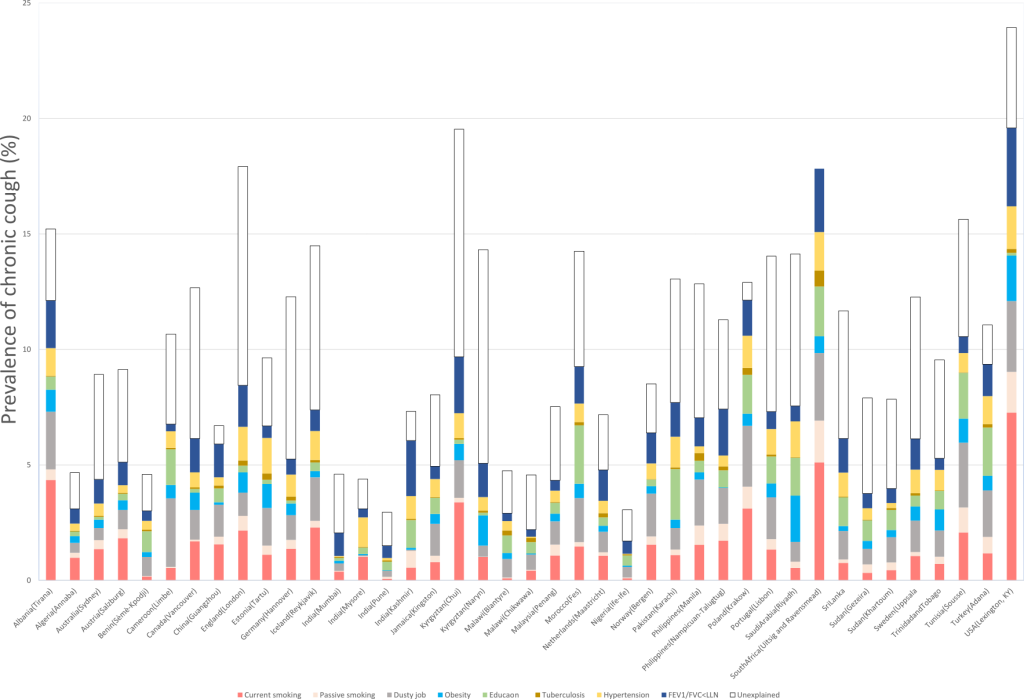

tory disease. It started with the intention to measure the prevalence, risk factors, and impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in different populations around the world. COPD is a common and serious lung condition that causes breathing difficulties, coughing, wheezing, and reduced quality of life. It is estimated that COPD affects around 300 million people worldwide and is a leading cause of death globally.

tory disease. It started with the intention to measure the prevalence, risk factors, and impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in different populations around the world. COPD is a common and serious lung condition that causes breathing difficulties, coughing, wheezing, and reduced quality of life. It is estimated that COPD affects around 300 million people worldwide and is a leading cause of death globally.