Editor’s Note:

As part of inclusive assessments project, we are excited to share narratives and lived experiences of neurodivergent students at Imperial. The first article in this series is penned by two 1st year students from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering (ESE).

This article highlights how designing teaching and assessment with inclusivity in mind can enhance learning experience for all students. There is emphasis on support around activities and skills development, flexibility for those who face logistical issues, and tailored support for those who need it.

The objectives of this article are:

- To raise awareness among students on what to expect in field trips

- To highlight challenges faced by neurodivergent students

- To highlight support offered by the department

- To share tips and advice to students on preparing for these field trips

Field trip Overview:

Geological fieldwork is the bedrock of geoscience education and degrees. It underpins all undergraduate courses in ESE, with students embarking on 2-5 field trips during their studies (depending on their degree stream). For 10 days, 1st year students were in Sorbas, Spain, conducting geological fieldwork.

With daily departures to the field at 0815 and a return to the field centre around 1600, students spent approximately 7 hours (maximum) in the field. A coach took the students to the field each day, followed by a walk/hike of varying difficulties from the drop-off point to the locality.

Assessment

The EART 40010 Geology in the Field module is worth 7.5 ECTS and comprises of multiple tasks, which are explained below.

Before the field trip (UK)

Students have 3 days of skills sessions before the field trip. At the end of each day an online multiple-choice quiz of roughly 10 questions was set to assess students’ understanding of field skills that they had learnt each day in skills week. This is worth 10% of the overall grade.

During the field trip (Spain)

In ESE, field notebooks are a major component of fieldwork. They carry the information of what students observed, interpreted and drew in the field. These are worth 30% of the module and the weighting of the notes increases with each day. This is due to the nature of student’s work improving as they become more experienced. Notebooks are handed in on day 9 of the field trip.

20% of the field module comes from two assignments using data from day 4 of the trip. It is assessed as a piece of coursework. Students are given two evenings to create a cross-section and a stereonet with their data, worth 10% each.

The other 40% is assessed in days 6-8 through a mapping exercise. Students construct a map showing the geological units and boundaries they have observed as well as any structural measurements, with the map 30% of the module and 10% for the cross-section. Students are also expected to extrapolate data from the map to create a cross-section of visible and hidden geology along a predetermined transect line. The high weightage reflects the improving nature of student’s work as they become more experienced. This means that weightage increases with time spent in the field.

Potential barriers for neurodivergent students during field trip

Accessibility and inclusion of neurodivergent students are a major component to consider in field trip. Given the unique nature of field trip, standard exam adjustments of “25% extra time” or rest breaks cannot be applied. Therefore, it is important that staff have the necessary tools and knowledge to listen and work with students on an individual basis to make field trip possible.

Performing under time pressure

Working in the field can often be fast paced as students move from outcrop to outcrop. This makes it less than ideal and posed many challenges for neurodivergent students. Writing field notes under these situations can particularly be difficult for students who may struggle with processing information or organising their ideas.

Overstimulation

Being in the field also means that there are infinite external factors beyond our control, one primarily being the weather conditions. Students with greater sensitivity to heat or sweat may find this particular trip challenging, as students work in the field with almost no cloud cover and ambient temperatures reaching low thirties. The aspect of being around other students all day can also be an overwhelming experience: murmuring, rustling bags and crowding together at small outcrops can all contribute to overstimulation.

Performing under uncertain conditions

The first four days consisted of visits to various localities, exposing students to metamorphic, igneous and sedimentary rocks across various settings: coastal to mountainous. They were staff-led, meaning staff and GTAs were available in proximity most of the time, informing students of the duration and the interpretation of each outcrop.

However, this was not the case for the last three days of the trip. Students were in small groups (2-4) to conduct independent mapping of an area (∼6 km²) in the Sorbas-Tabernas basin. Before working independently in the field, a quick recap of the skills required to map effectively was given. Staff accompanied larger groups of students to their first few outcrops before eventually breaking off into mapping pairs. GTAs and staff were scattered around the area after providing initial guidance to mapping, meaning that questions could only be asked when students encountered them by chance.

For neurodivergent students this could be a challenge. Independent mapping has an open-ended nature and involves minimal instructions; the lack of structure can be daunting for many.

“Having a structured plan is like a safety net for me, so I knew mapping would be a stretch out my comfort zone. Luckily, I was able to receive 1 on 1 support from staff for the majority of the first day to build up my confidence in mapping. This helped me feel confident to join a larger mapping group of 4 and work as part of a team” – Grace Wiggall, 1st year ESE student

Communication

For safety, all fieldwork is carried out in pairs or groups. This may be difficult for students of some neurotypes. Communication issues can arise as pairs must make decisions regarding how they manage their time, what outcrops they might visit and discuss interpretations of what they have observed.

“For somebody who struggles with communication and motor control, mapping was particularly difficult given the amount of land we had to cover by foot, which was aggravated by the heat. The hill slopes were covered by sharp, dry vegetation, all of those in my group including myself bled from impalement alongside injuries from falls and topples during our hike to cover the sheer vertical and horizontal distances. It was particularly challenging to keep up the hiking pace in my group, and to communicate my struggles with my group mates. However, being able to work with my peers in such a special location was very fulfilling” – Kevin Jang, 1st year ESE student

Recovery time

All these challenges consume a lot of energy to be able to navigate. Being offered time to wind down is incredibly important for students, especially for neurodivergent individuals, considering the cognitive load that field trips create.

Highlighting inclusive aspects of implementation

Several elements of the field module have been adapted to support neurodivergent individuals, but they also benefit the entire cohort.

Before the field trip

Field Guide

Students can access the electronic field guide a month in advance and are provided with a physical field guide more than a week prior to departure. This contained nearly all information on the trip to detail such as what to expect each day and the details of the assignment and geological information of all the localities.

Briefings

There are also two briefing sessions, one in November and one in March. These were to prepare students logistically and make them aware of any equipment they may need to purchase. Students are also required to undertake first aid training which takes place in the autumn term.

Skills sessions

As mentioned in the assessments section, in addition to the guide, students had skills sessions which were designed to familiarise students with technical equipment for the first time.

Practice field trip

Prior to the main trip to Spain, students also had a mini field trip to Clapham Common, an exercise with fictitious outcrops to simulate the field, where students had to produce a cross-section and a map based on the structural measurements they obtained.

Kevin found this trip to Clapham Common helpful. He was exposed to the expectations of the summative field trip beforehand. These were all tasks’ students eventually had to do in Spain independently. Without these practices, many students would have struggled to progress in their tasks, particularly neurodivergent or disabled students.

During the field trip

Staff cars

There were two staff cars available to cater for emergencies or students with any specific support needs. Cars could directly reach the locality, eliminating the need for the walk. There were numerous students who benefitted from this option, ranging from a physical condition that made walking difficult, to sensory challenges.

High staff-to-student ratio

Students were able to receive better support and benefit from the provisions due to the high staff-to-student ratio in the field. There were 5 staff and 5 GTAs for 45 students. It is rare for undergraduate students to experience such a high staff-to-student ratio during their course, with the exception of the Year 4 MSci project.

Tailored support

Being able to tailor support to individual students is something the department has been able to do well, arranging meetings and listening carefully to what students require to succeed. One such tailored support has been to offer a single room to a student due to their specific needs.

“Being able to have time to myself in the evenings helped me immensely. Fortunately, the department was able to provide me with a single room, which was vital to me being able to conserve energy and social battery throughout the whole 10 days … I am incredibly grateful that the department were able to work with me as a student to make fieldwork both accessible and enjoyable. I look forward to participating in future field trips and seeing others benefit from the adjustments available.” – Grace Wiggall, 1st year ESE student

Alternative to field trip

Written coursework

The Department of Earth Science and Engineering offers alternative formats of this 10-day module. For those who are unable to be in the field due to visa, scheduling or medical reasons, there is an option of a written desk-based coursework, where students will be asked to produce a written report outlining the geological history of the field area.

Although this may be appealing to the neurodivergent community, fieldwork remains as a core learning process for the field of geoscience. Students without the knowledge and skills of being in the field may reduce or limit their opportunities or career pathways. For example, some careers such as exploration geologist requires prior fieldwork experience. It is also important to note that there are plenty of non-field-based geoscientists who have never done fieldwork and yet lead fulfilling industry and/or academic jobs.

Fieldwork using Virtual Reality (VR)

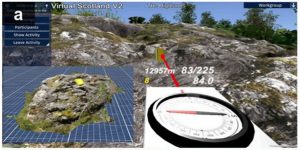

Another option is conducting fieldwork in the virtual realm, which was heavily used during the pandemic, housed in the Earth Science & Engineering Remote Classroom (ESERC) software. It provides an immersive experience of the field of geology alongside live interaction with fellow students and staff. Some important localities offer close-up views of the rock, allowing students to have similar experiences of using a hand-lens (Genge et al., 2024).

The ESERC team have made several additions to the programme to further enhance inclusivity such as:

- Glowing footprint trails

- Allowing users to emplace markers in desired locations

- Option to turn off the ambient environmental sound (this can be useful if the sound of bees, footsteps and movement of grass is overstimulating)

However, available functions may vary depending on the virtual field course due to programming. (Guillaume, Laurent & Genge, 2023).

Challenges of virtual fieldwork

Although virtual field trips may be able to remove some parts of anxiety derived from being in the field, it poses other challenges to neurodivergent students. Students with ADHD may struggle with spatial awareness and attention span (Luo et al., 2019) due to prolonged hours of looking at the screen.

Challenges with navigating in the virtual environment using a keyboard and/or a mouse may be more prominent in dyspraxic students, given the small room for physical movement and the requirement for fine motor skills. Finally, virtual fieldwork may not offer similar learning opportunities of seeing the formation with one’s eyes. Feeling the texture of rock surfaces, or taking a measurement with a compass clinometer, this simply cannot be replicated in the virtual world with existing technologies.

Advantages of virtual fieldwork

Despite these challenges, virtual fieldwork offers some advantages. For example, in the field, students are given limited time at each outcrop, where fieldwork may even cease abruptly due to extrinsic factors. Additionally, it is not possible to revisit outcrops. These challenges can be overcome by using virtual fieldwork.

Genge et al., 2024 discovered that students were still in the virtual field for socialising even after virtual reality lessons finished, suggesting high levels of student comfort and satisfaction with the environment. Virtual fieldwork was assessed in the similar manner compared to its in-person counterpart; students collected the data virtually but still produced similar quality field maps which were indistinguishable to in-person maps to an experienced marker (Genge et al., 2024).

Kevin believes that virtual fieldwork should be complementary to in-person fieldwork – neurodivergent students would greatly benefit from the option and the time to revisit the outcrop virtually and familiarise themselves with the environment and practice the skills necessary to carry out in-person fieldwork.

Tips and advice for students

Advice for neurodivergent students

- Make yourself known to your DDO and wellbeing advisor. Let them know that you feel you may need adjustments to carry out fieldwork. Grace recommends thinking of this at least 2 months before the fieldwork begins

- Ask for any resources you need in advance (e.g. a draft copy of the field guide, as it remains almost the same year to year)

- You can discuss what adjustments might work for each particular field trip with the DDO and Field trip leader.

- Meet with the field trip leader or senior tutor to discuss concerns at any point before the field trip. You can clarify details such as what to expect and what you need to prepare before the departure date and ask any questions.

- Find out who you might be in a group with and prepare yourself for the social aspect of the trip.

Skill specific tips for fieldwork (for everyone)

- Note-taking – Make sure you bring any tool that will help you with note-taking, mapping, sketching (e.g. Grace found using iPad in the evenings when completing map work to be useful)

- Time management – Set timers when working at each outcrop so you can cover enough ground in the day.

- Reading comprehension – Ask lecturers and GTA for help if something in the field guide is unclear (this is allowed, in fact, encouraged and totally okay!)

- Depth of understanding / subject knowledge – When in the field, ask GTAs questions when you can! If there is something you might find confusing, stick step-by-step instructions or important notes into the back of your notebook. Grace found using the compass difficult to remember, so wrote a step-by-step guide in the back of her notebook.

- Interpreting data/ findings –Talking out loud or in groups in the evening when interpreting results can make it much easier to process and understand.

- Teamwork– If you are comfortable, let your team know that some things might be hard for you and what you might want from them (e.g. for them to be clear when explaining things)

Advice from field trip leader

The ESE team organising field trips has been great at working with students and offering advice and discussing what can be done to improve this course.

“No field trip is static from year to year. Each year the field trip is reviewed, and changes are made to improve the experience: whether this is logistical (like the new field toilet this year), educational, or social. The staff who lead these trips want feedback on how things are going (before, during, and after) the trip is run. This feedback is then used to craft the next version of the trip. Don’t be afraid to give feedback to the staff, both what worked well and what didn’t. This can of course come via the rep, network or other channels. We really do listen!”

– Dr. Alan R.T. Spencer, Field trip Leader

Authors: Grace Wiggall and Kevin Jang

Contributor: Dr. Alan Spencer, Senior Strategic Teaching Fellow, Earth Science and Engineering

Editor: Dr. Vijesh Bhute, Senior Teaching Fellow, Chemical Engineering

Please share any feedback or comments in the comments section below this article. You can also leave your feedback anonymously by using this feedback form.

If you would like to share your own experience and raise awareness around inclusivity, please get in touch with Dr. Vijesh Bhute (v.bhute@imperial.ac.uk).