Black History Month allows everyone to share, celebrate, and understand the impact of black heritage and culture. People from African and Caribbean backgrounds have been a fundamental part of British history for centuries. Although it was launched in America in 1926 by Carter G Woodson, the first Black History Month in the UK took place in 1987, the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean. It was arranged by Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, who came to the UK from Ghana as a refugee. Like Woodson before him, he wanted to challenge racism and celebrate the history of black people.

To mark Black History Month, the Institute of Infection looked back to some of the most influential Black scientists throughout history and collaborated with current Imperial researchers to celebrate their accomplishments and visions for the future.

A look back at history

Mary Seacole (1805-1881): Carer of victims of cholera and yellow fever epidemics; heroine of the Crimean War

Mary was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1805. Her mother was black, and her father was a white army officer. From the age of 12, she helped her mother run a boarding house where they treated sick or injured soldiers, and, at 15, she travelled to England and learned about European medicine. Between 1850 and 1851, Mary nursed victims of cholera epidemics in Kingston and Cruces, Panama, using mustard emetics to make the patient vomit, warm clothes to combat chills, mustard plasters on the stomach and back and calomel in varying doses.

Mary was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1805. Her mother was black, and her father was a white army officer. From the age of 12, she helped her mother run a boarding house where they treated sick or injured soldiers, and, at 15, she travelled to England and learned about European medicine. Between 1850 and 1851, Mary nursed victims of cholera epidemics in Kingston and Cruces, Panama, using mustard emetics to make the patient vomit, warm clothes to combat chills, mustard plasters on the stomach and back and calomel in varying doses.

In 1853, Mary returned to Kingston for the yellow fever epidemic and supervised nursing services at the British Army’s headquarters before transforming her mother’s old lodging house into a hospital. In 1853, after being denied permission by the British War Office in England to serve as a nurse in the Crimean War, she funded her own trip there and set up a hotel to treat soldiers and tend to those on the front lines.

On her return to London, she continued fundraising efforts, including the Seacole Fund Grand Military Festival, which drew in thousands of attendees. She also published her bestseller book.

Mary was lost to history for 100 years, but in 2004, she was voted the Greatest Black Briton, and in 2016, her statue was unveiled in the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital, London.

Dr George Rice (1848-1935): Assistant to Sir Joseph Lister and Chief Vaccinator

Dr George Rice was born in New York, USA in 1848. After graduating from Dartmouth and training as a surgeon in Edinburgh, he served as a house surgeon at the Royal Edinburgh Infirmary, where he assisted Sir Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic treatment. Dr Rice then moved to Manchester, worked in the Royal Infirmary as a house physician, and held resident appointments at the Chorlton Union Hospital and Woolwich and Plumstead Infirmary. He also held office under the Metropolitan Asylums Board at the Downs Ringworm Hospital, and was a resident medical officer at the Fulham Workhouse.

Dr George Rice was born in New York, USA in 1848. After graduating from Dartmouth and training as a surgeon in Edinburgh, he served as a house surgeon at the Royal Edinburgh Infirmary, where he assisted Sir Joseph Lister, the pioneer of antiseptic treatment. Dr Rice then moved to Manchester, worked in the Royal Infirmary as a house physician, and held resident appointments at the Chorlton Union Hospital and Woolwich and Plumstead Infirmary. He also held office under the Metropolitan Asylums Board at the Downs Ringworm Hospital, and was a resident medical officer at the Fulham Workhouse.

In later years, he worked at local schools for poor and orphaned children, specialised in treating patients with epilepsy, and became District Medical Officer and Chief Vaccinator for Sutton and Cheam areas which now contains a community garden dedicated to him.

Read more about Dr George Rice

Dr Harold Moody (1882-1947): Doctor and ambassador for Britain’s Black Community

Dr Harold Moody was born in 1882 in Jamaica, then moved to London in 1904 to study medicine at King’s College. After qualifying as a doctor in 1910, he applied for a job at the hospital but was denied due to racial discrimination. He would not allow racism to hold him back and, instead, started his own surgery in Peckham in 1913. Dr Moody treated the children of poor families for free, and people would come from near and far to see him. Dr Moody also became an influential community leader and an ambassador for Britain’s Black community. In 1999, Consort Park in Peckham was renamed Dr Harold Moody Park, in 2007, a bronze portrait of him was put on display in Peckham Library, and in 2020, Dr Moody was included in Patrick Vernon and Angelina Osborne’s book “100 Great Black Britons”.

Read more about Dr Harold Moody

Alice Ball (1892-1916) Inventor of the “Ball Method” treatment for leprosy

Alice Ball became the first African American and woman to graduate with an MSc in Chemistry in 1915 from the University of Hawaii. At 23, she became the University’s first female chemistry instructor. At the time, the only treatment for leprosy was chaulmoogra oil; however, it was almost impossible to use effectively. Ball found a way to create a water-soluble solution of the oil’s active compounds that could be injected safely with minimal side effects. It was called the “Ball Method” and became the first successful treatment.

Alice Ball became the first African American and woman to graduate with an MSc in Chemistry in 1915 from the University of Hawaii. At 23, she became the University’s first female chemistry instructor. At the time, the only treatment for leprosy was chaulmoogra oil; however, it was almost impossible to use effectively. Ball found a way to create a water-soluble solution of the oil’s active compounds that could be injected safely with minimal side effects. It was called the “Ball Method” and became the first successful treatment.

For over 30 years, her discovery made a huge impact on thousands of infected individuals until sulfone drugs were introduced. Alice died at the age of 24, and the president of the University of Hawaii continued her research without giving her any credit for the discovery; she remained largely forgotten from scientific history until recently. February 29 is now known as “Alice Ball Day” in Hawaii, and the Alice Augusta Ball scholarship has been established to support students pursuing a degree in chemistry, biology, or microbiology at its University.

Professor Augustus (1883 – 1959) and Dr Jane Hinton (1919 –2003): Prominent bacteriologist and co-inventor of the Mueller-Hinton agar

Dr Jane Hinton was born in May 1919 in Canton, Massachusetts. Her mother was a teacher, and her father, Professor William Augustus Hinton, was a bacteriologist and one of his era’s most prominent African-American medical researchers. In the 1920s, Augustus developed a test for syphilis that was widely used until newer methods were developed after World War II. Augustus was the first African-American professor at Harvard Medical School and the first African-American to write a medical textbook. His daughter, Jane, joined his lab after graduating in 1939 and became an assistant to John Howard Mueller in Harvard’s Department of Bacteriology and Immunology. She also helped develop the Mueller-Hinton agar, which has become one of the standard methods used to test bacterial resistance to antibiotics. After gaining her doctorate in Veterinary Medicine, she joined the Department of Agriculture as a federal government inspector in Framingham, Massachusetts, and was involved in research and response to outbreaks of disease in livestock.

Dr Jane Hinton was born in May 1919 in Canton, Massachusetts. Her mother was a teacher, and her father, Professor William Augustus Hinton, was a bacteriologist and one of his era’s most prominent African-American medical researchers. In the 1920s, Augustus developed a test for syphilis that was widely used until newer methods were developed after World War II. Augustus was the first African-American professor at Harvard Medical School and the first African-American to write a medical textbook. His daughter, Jane, joined his lab after graduating in 1939 and became an assistant to John Howard Mueller in Harvard’s Department of Bacteriology and Immunology. She also helped develop the Mueller-Hinton agar, which has become one of the standard methods used to test bacterial resistance to antibiotics. After gaining her doctorate in Veterinary Medicine, she joined the Department of Agriculture as a federal government inspector in Framingham, Massachusetts, and was involved in research and response to outbreaks of disease in livestock.

Read more about Dr Jane Hinton

Read more about Professor Augusts Hinton

Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu (1947-): UK’s first sickle cell and thalassemia nurse specialist who fought to make the NHS fairer

Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu was born in Birmingham in 1947 and identifies as Irish/Nigerian heritage. She started working for the NHS as a school nurse assistant in Wolverhampton at 16 and was also a health visitor and tutor for the black community in London. In 1979, she helped to establish the first nurse-led UK Sickle & Thalassaemia Screening and Counselling Centre, and from 1990-1997, she worked at the Institute of Child Health, UCL as a Lecturer then Senior Lecturer in Community Genetic Counselling. She later became a Professor and Dean of the nursing school at the University of West London.

Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu was born in Birmingham in 1947 and identifies as Irish/Nigerian heritage. She started working for the NHS as a school nurse assistant in Wolverhampton at 16 and was also a health visitor and tutor for the black community in London. In 1979, she helped to establish the first nurse-led UK Sickle & Thalassaemia Screening and Counselling Centre, and from 1990-1997, she worked at the Institute of Child Health, UCL as a Lecturer then Senior Lecturer in Community Genetic Counselling. She later became a Professor and Dean of the nursing school at the University of West London.

In 1998, she established the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice, which she led until her retirement in 2007. The Centre, which was set up to address racial inequalities in the nursing profession, offered a framework for student nurses to learn about infections and ran campaigns to increase the number of nurses from minority ethnic backgrounds. Dame Anionwu improved awareness of sickle cell disease within the NHS for forty years. She was granted Damehood (DBE) in 2017 in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List for her services to nursing, received the Pride of Britain Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019, and was honoured with the Order of Merit in 2022.

Read more about Professor Dame Elizabeth Nneka Anionwu

Visions of the future: Meet some of the Black researchers at Imperial working to improve infection

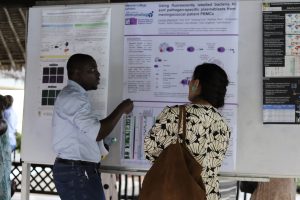

Professor Faith Osier: working to ‘Make Malaria History’

Professor Faith Osier studied medicine in Nairobi, Kenya, and while working as a Junior Doctor (1998-2001) in a rural hospital in Kilifi, she would admit up to five children with malaria to the high-dependency unit. Many didn’t survive. This inspired her to think about prevention and how she could stop children from getting malaria in the first place to ‘Make Malaria History’.

Professor Faith Osier studied medicine in Nairobi, Kenya, and while working as a Junior Doctor (1998-2001) in a rural hospital in Kilifi, she would admit up to five children with malaria to the high-dependency unit. Many didn’t survive. This inspired her to think about prevention and how she could stop children from getting malaria in the first place to ‘Make Malaria History’.

Professor Osier won an African Research Leader Award, funded by the UK MRC and the former UK Department for International Development, which kickstarted multicentre research studies that evolved into the SMART South–South Malaria Antigen Research Partnership with Ghana, Senegal, Mali, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burkina Faso. Her work focusses on mechanistic studies to help answer why the burden is disproportionately high in infants and young children and why this vulnerable group becomes increasingly resistant with age. This insight will be critical for developing malaria vaccines.

Professor Osier is currently Chair of Immunology and Vaccinology in the Department of Life Sciences and the Co-Director of Imperial’s Institute of Infection. In 2019, she became the first African (and only the second woman) to become President of the International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS). Professor Osier is passionate about leadership issues of equity and diversity, particularly elevating the role of women. She is a role model, motivator, and passionate supporter of scientists from low and middle-income countries.

Professor Faith Osier: “Celebrating the achievements of black scientists is vital for changing mindsets about who we are and what we bring to the table – a great step forward towards inclusivity”.

Read more about Professor Faith Osier

Dr Calvin Tiengwe: Sir Henry Dale Fellow contributing to the understanding of African sleeping sickness

Dr Calvin Tiengwe is a Sir Henry Dale Fellow at the Department of Life Sciences. Originally from Cameroon, he has lived in the UK and USA for 20 years, researching various aspects of trypanosome molecular biology that make them successful pathogens of humans and animals. His fellowship, funded by the Royal Society and Wellcome Trust, allowed him to set up an independent research program at Imperial. He earned his PhD from the University of Glasgow, then undertook postdoctoral fellowships at Johns Hopkins and SUNY Buffalo, USA. More about his work can be found here.

Dr Calvin Tiengwe is a Sir Henry Dale Fellow at the Department of Life Sciences. Originally from Cameroon, he has lived in the UK and USA for 20 years, researching various aspects of trypanosome molecular biology that make them successful pathogens of humans and animals. His fellowship, funded by the Royal Society and Wellcome Trust, allowed him to set up an independent research program at Imperial. He earned his PhD from the University of Glasgow, then undertook postdoctoral fellowships at Johns Hopkins and SUNY Buffalo, USA. More about his work can be found here.

“Black History Month shines a light on underrepresented minorities within our communities. It promotes an inclusive culture today and inspires the next generation to be equal contributors in a world where equity and inclusivity are inherent. My hope is that, in my career and beyond, we move towards a future where every day reflects the rich diversity of our humanity.” – Dr Calvin Tiengwe

Read more about Dr Calvin Tiengwe

Dr Julia Makinde: Developing vaccines and strengthening of research capacity

Dr Julia Makinde was born in Delta State, Nigeria, where she obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Zoology from the University of Ibadan. The foundations of her career were established at the University College London and Cardiff University Wales, where she obtained a Master’s degree in Molecular Medicine and PhD in Medicine/Immunology, respectively.

Dr Julia Makinde was born in Delta State, Nigeria, where she obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Zoology from the University of Ibadan. The foundations of her career were established at the University College London and Cardiff University Wales, where she obtained a Master’s degree in Molecular Medicine and PhD in Medicine/Immunology, respectively.

Her interest in translational science fuelled her contributions to our understanding of the fundamental rules that govern immune cell interaction with antigens derived from self, vaccines, and infectious pathogens. Further work in global health research has focused on the development of novel vaccine candidates against infectious pathogens like HIV and the strengthening of research capacity.

Dr Makinde is a Senior Manager of Clinical Immunology and Honorary Lecturer based at the IAVI Human Immunology Laboratory. She currently works on the ADVANCE programme, funded by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, a five-year cooperative agreement to further the progress of HIV research, working with a network of researchers from around the world.

“Black History Month is a reminder of our collective history and a universal call for an inclusive and equitable society. Through my career, I hope to be the positive change that I yearn for.” Dr Julia Makinde

Read more about Dr Julia Makinde

Dr Wayne Mitchell: Championing and leading equality, diversity and inclusion at Imperial

Dr Wayne Mitchell is the joint Associate Provost for Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion, Senior Teaching Fellow, and Senior Tutor in the Department of Immunity and Inflammation.

Having graduated from the University of Birmingham with a degree in Biomedical Science, he completed a PhD at University College London in Molecular Genetics before undertaking postdoctoral positions in Cancer Biology and Immunology. He has always been interested in understanding what makes students learn and has taught at all levels of the British Education system. He completed a Master’s in Education at Imperial College, focusing on the experiences of Black British students at elite universities and how their ‘minority status’ impacts on their sense of belonging and identity.

Dr Mitchell’s passion and flexible working approach has had a positive impact on many students’ academic and personal experience, as well as other staff. In 2018, he was the recipient of the President’s Medal for Excellence in Supporting the Student Experience. He joined Imperial College’s Race Equality Charter-Self Assessment Team in 2019 to help understand the impact that being a member of a minoritized groups at Imperial College has on their sense of belonging and identity as a BME students. He is Co-Chair of Imperial College Race Equity Staff Network -Imperial As One, which promotes greater understanding and inclusivity for the diverse College community. One of his roles includes hosting Imperial As One’s weekly interview series, Belonging, which explores the lived experience of individuals from minoritized groups. In 2021, along with the Co-chairs of Imperial As One, he received the President’s Medal for Excellence for Community and Culture. He was recently appointed joint Associate for Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion at Imperial along with Professor Lesley Cohen.

“This year we’ve celebrated 75 years of the arrival of British citizens on the Empire Windrush and the birth of the NHS, two momentous events, so it’s important that we take the time to educate and celebrate the contributions that the African Diaspora has made to the everyday life of Britain and across the globe. To quote the late Stuart Hall, ‘We are here because you were there’ meaning that all our histories are connected and we need to recognise and acknowledge that fact. BHM shines a spotlight on the many great achievements and connections and encourages everyone to embrace all aspects of our identities as Black British People who Belong. My hope is that BHM will one day be viewed as British History Months and not be limited to October but celebrated 24/7/365 because Black history is British History recognised for it’s uniqueness and included in the everyday narrative of Britain.” Dr Wayne Mitchell

Read more about Dr Wayne Mitchell

Dr Dauda Ibrahim: Transforming RNA vaccine manufacturing

Dr Dauda Ibrahim is a postdoctoral research associate in the Clean Energy Process (CEP) Laboratory, Department of Chemical Engineering. He received both his MSc and PhD degrees in Chemical Engineering from the School of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Science, University of Manchester. Dr Ibrahim’s research focuses on the development of systematic frameworks for computer-aided working fluid design and optimisation of organic Rankine cycle systems. Dr Ibrahim also worked on pandemic-response adenoviral vector and RNA vaccine manufacturing. This model-based assessment provides key insights to policymakers and vaccine manufacturers for risk analysis, asset utilisation, directions for future technology improvements, and future epidemic/pandemic preparedness, given the disease-agnostic nature of these vaccine production platforms. He was also first author on ‘Model-Based Planning and Delivery of Mass Vaccination Campaigns against Infectious Disease: Application to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK’ paper which showed by integrating demand stratification, administration and the supply chain, the synergy amongst these activities can be exploited to allow planning and cost-effective delivery of a vaccination campaign against COVID-19 and demonstrates how to sustain high rates of vaccination in a resource-efficient fashion.

Dr Dauda Ibrahim is a postdoctoral research associate in the Clean Energy Process (CEP) Laboratory, Department of Chemical Engineering. He received both his MSc and PhD degrees in Chemical Engineering from the School of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Science, University of Manchester. Dr Ibrahim’s research focuses on the development of systematic frameworks for computer-aided working fluid design and optimisation of organic Rankine cycle systems. Dr Ibrahim also worked on pandemic-response adenoviral vector and RNA vaccine manufacturing. This model-based assessment provides key insights to policymakers and vaccine manufacturers for risk analysis, asset utilisation, directions for future technology improvements, and future epidemic/pandemic preparedness, given the disease-agnostic nature of these vaccine production platforms. He was also first author on ‘Model-Based Planning and Delivery of Mass Vaccination Campaigns against Infectious Disease: Application to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK’ paper which showed by integrating demand stratification, administration and the supply chain, the synergy amongst these activities can be exploited to allow planning and cost-effective delivery of a vaccination campaign against COVID-19 and demonstrates how to sustain high rates of vaccination in a resource-efficient fashion.

“The importance of Black History Month is to create awareness, honour, celebrate, and promote the contributions and achievements of black people within the UK and across the globe, thus inspiring the young generation” – Dr Dauda Ibrahim

Read more about Dr Dauda Ibrahim

Dr Fadil Bidmos: Tackling bacterial meningitis, a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in children

Dr Fadil Bidmos, an Advanced Research Fellow in the Department of Infectious Disease, focuses on developing novel and cheap-to-produce vaccines that will target the two leading causes of bacterial meningitis, meningococcus and pneumococcus. He uses advanced tools to develop this vaccine in a “next generation” format.

“Black History Month is essential because it is a time during which the struggles, triumphs, and traditions of the Black community are brought to the forefront of public consciousness. Activities during the month help to break harmful biases and misconceptions, challenge prejudices, inspire future generations, and foster cultural appreciation. The lived experiences of black individuals, past and present, are also on full display during this month; this knowledge is essential in the creation of a more inclusive and equitable society, one in which the invisibility, disregard and undervaluation of blacks is non-existent. By continuing to educate ourselves about black history and acknowledging the systemic barriers that (unfortunately) still exist, we can work towards a future where everyone is treated with the dignity and respect they deserve.” Dr Bidmos

Read more about Dr Fadil Bidmos

To be introduced first is

To be introduced first is  What opportunities would you like ECR to have to help with your careers?

What opportunities would you like ECR to have to help with your careers?