If you had access to a 3D printer, what would you print? Something fun, something useful? How about both?

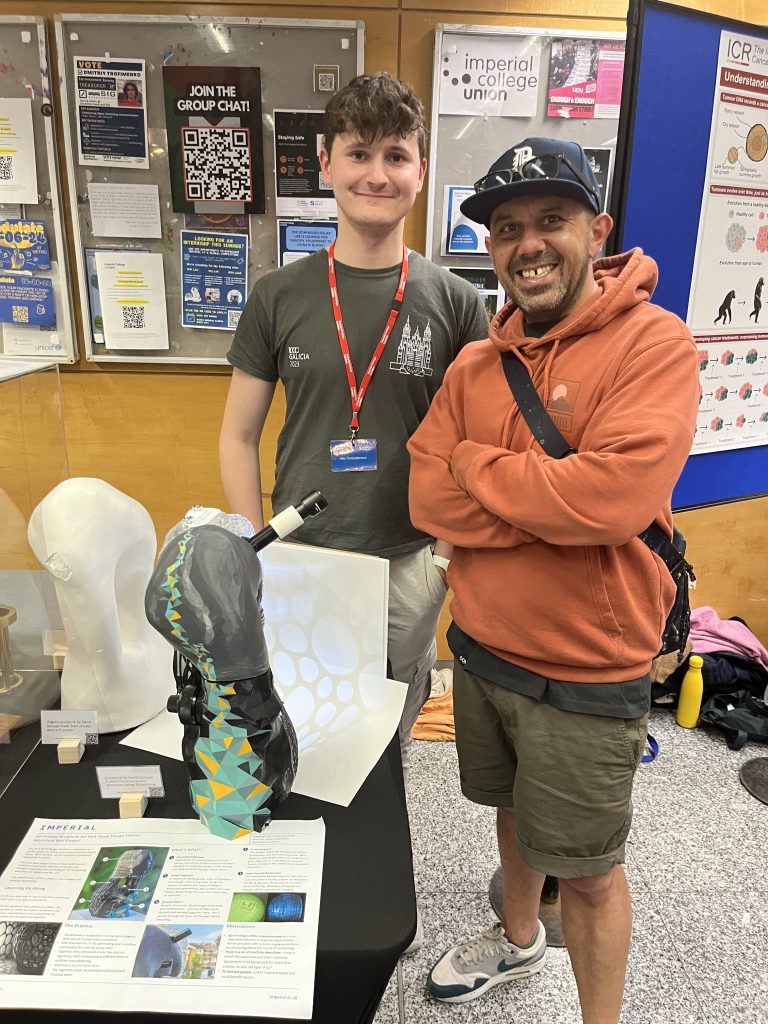

Alex Christopherson, a final year undergraduate student in Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London and David Samuel, an artist based in Park Royal Design Studios, collaborated to create a 3D printed sculpture that doubles as a microscope and allows you to see a 3D printed Queens Tower 100,000 times smaller than the real one! Engineering and art coming together to 3D print a sculpture.

We talked to both Alex and David for our IMSE podcast, ‘Never lick the spoon’ in the episode #30. They discussed the design and production of the sculpture and how an engineer and an artist communicated throughout the project.

From chicken wire and plaster to polymers and resins

The project started with David making a sculpture using chicken wire and plaster in his signature organic form. The only requisite from Alex was the size limit. The sculpture had to fit in the 3D scanner, which then produced a million coordinates just for the outer shell. Early on, Alex envisioned how the sculpture could be divided into two sides which then became five different segments, each showcasing a distinct form of additive manufacturing.

The 3D printed sculpture, segment by segment

The bottom of half #1 is the decimated segment, inspired by the internal structure of bones. Just like the human skeleton, it was designed to carry the load of the structure while minimising its own weight. Right above, the tendril segment aims to resemble roots and vines. It follows on the idea that in nature, ease of fitting leads to very relaxed geometries, unlike the usual square shapes found in manufacturing.

Alex then wanted to show how 3D printing is technically 2D. Thin layers are printed, stacked and bonded together to form a 3D structure. To show this, he laser-cut 42 layers from Perspex found in Imperial… previously used to separate people during the return to work in the Covid-19 pandemic!

These three segments completed half #1. What about the other half?

Finest resolution 3D printer in the planet

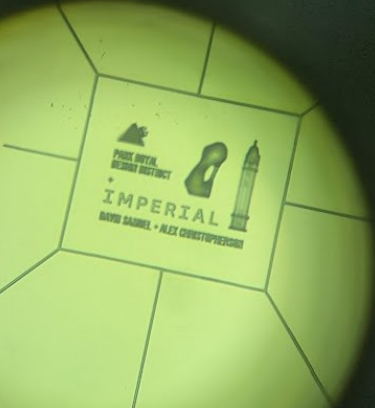

microscope. From left to right, miniature PRDD and Imperial logo, sculpture and Queens Tower. The nanoscribe 3D printer was used to print these objects onto a glass slide. Image credit: Alex Christopherson

In his quest to showcase all the 3D printing methods available at Imperial, Alex found the nanoscribe, a 3D printer with the finest resolution in the world. He used it to 3D print Queens Tower at 1:100,000 scale on a glass slide. The print is so small, it cannot be seen with the bare eye, it requires a microscope. The team found an old microscope at Imperial. They took it to the workshop, dismantled it and saved the essential pieces: objective, eye piece and focus.

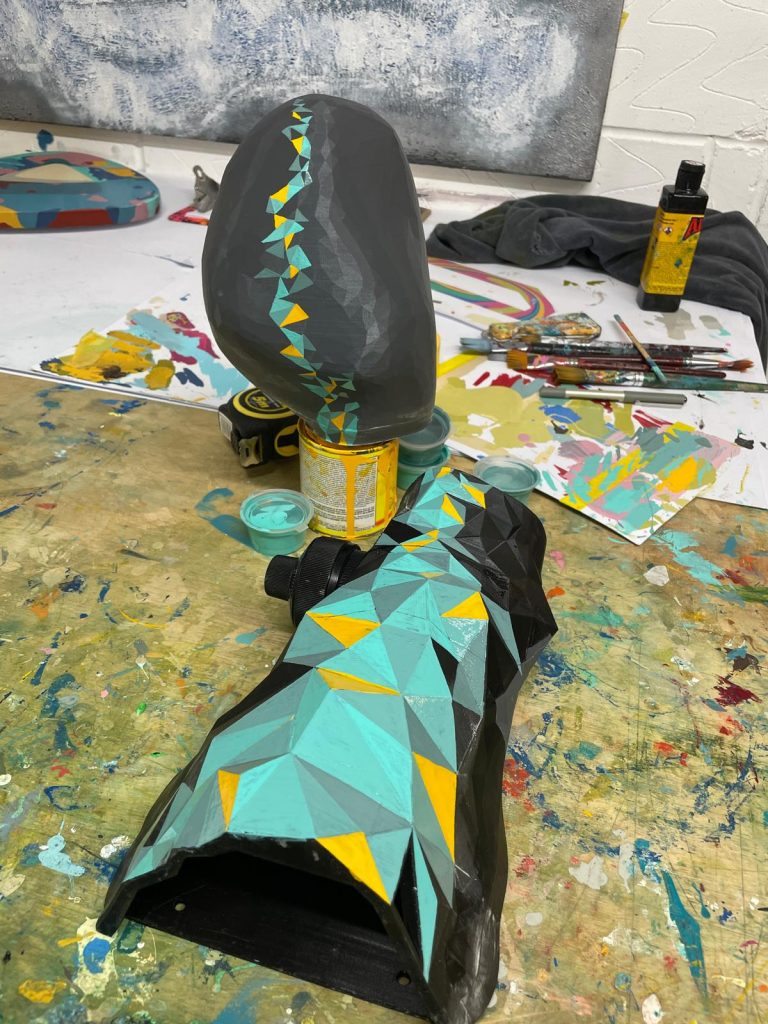

This hidden microscope guided the design and 3D print of the half #2. Alex showed David how to tessellate the surface using a computer programme and he designed a changing section as you move up in the sculpture. At the bottom, it is formed by large, clunky, angular low-resolution triangles that become smooth, almost curved, at the top.

David painted the triangles he designed for the second half of the sculpture. He used yellow to symbolize life and the humanity of the process and teal and grey which he associates with science and research.

Alex then assembled the sculpture.

Ta da!

Beyond the sculpture

Visitors to the London Craft Festival and to the Great Exhibition Road Festival were able to see the sculpture and hear from Alex and David about the story behind the project. The engaging nature of the microscope sparked curiosity and a lot of questions!

In total, including all the tests, it took 1,000 hours to print. While waiting for the printer to finish, Alex also collated a list of 3D facilities available at Imperial to expand its use beyond solving engineering problems.

A corridor between Design Studios and Imperial

But how did the collaboration start? Prof Ambrose Taylor, Alex’s tutor, and Johnny Brewin, from PRDD, had connected to bring together Imperial students based at North Acton Halls of Residence and artists based at the studios. Both places are located very close to each other but, separated by an old pathway, had not come together to collaborate.

This project learnt by doing, showing how engineering and art can connect people to push boundaries and explore new ideas. Both Imperial and PRDD hope this is only the beginning.

Bonus track

If you have listened to the podcast, you will now know that Alex did not watch the 3D printer print. However, Annemarie does look at the oven while she is baking a cake. You might be wondering if Alex went back to the workshop to print a miniature sculpture, just like Elena carries a photo of her old favourite microscope. We thought this could be the best way to introduce ourselves as the current hosts of ‘Never lick the spoon’ podcast!