Same job, different health outcomes

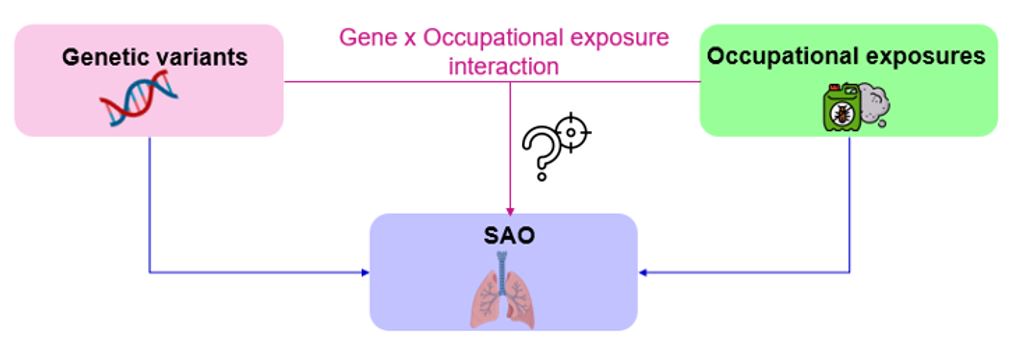

Why do some people develop lung problems after years of workplace exposure while others do not? Two workers might share the same job, be exposed to the same harmful substances, yet only one goes on to develop lasting lung damage.

Exploring the early stages of lung disease

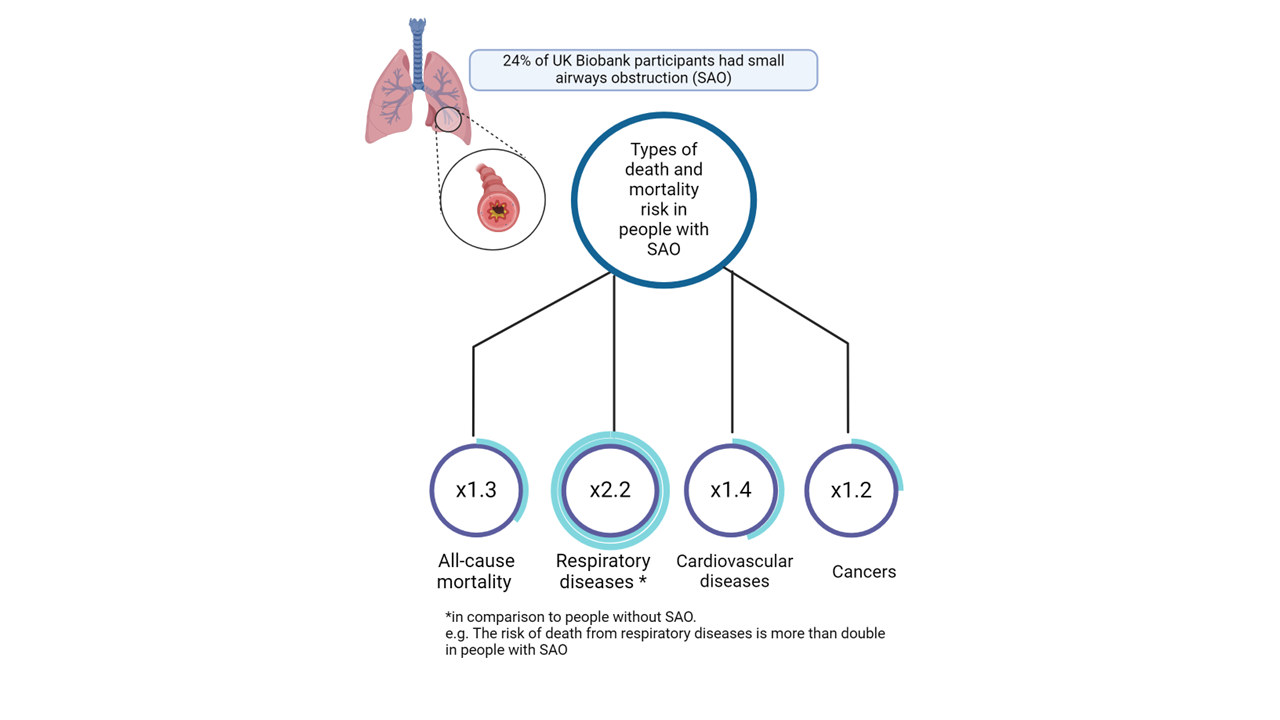

Small airways obstruction (SAO) is an early and often silent sign of chronic obstructive respiratory disease (COPD). SAO reflects the narrowing of the small airways of the lungs and can appear many years before it progresses to the large airways or presents with respiratory symptoms. Understanding these early signs of disease is important in preventing chronic lung disease later in life.

Combining genetics and workplace exposures

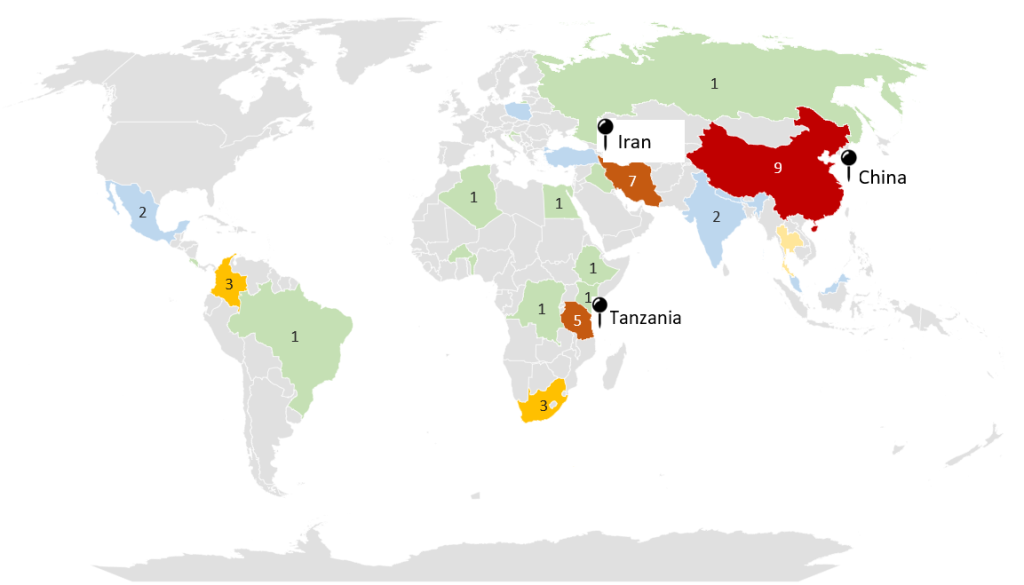

Using data from more than 147,000 UK Biobank participants, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify genetic variants associated with SAO. We then investigated whether these variants interact with occupational exposures to modify the risk of SAO.

What are the key messages?

- We identified 36 genetic variants associated with SAO.

- Eight variants significantly interacted with occupational exposures.

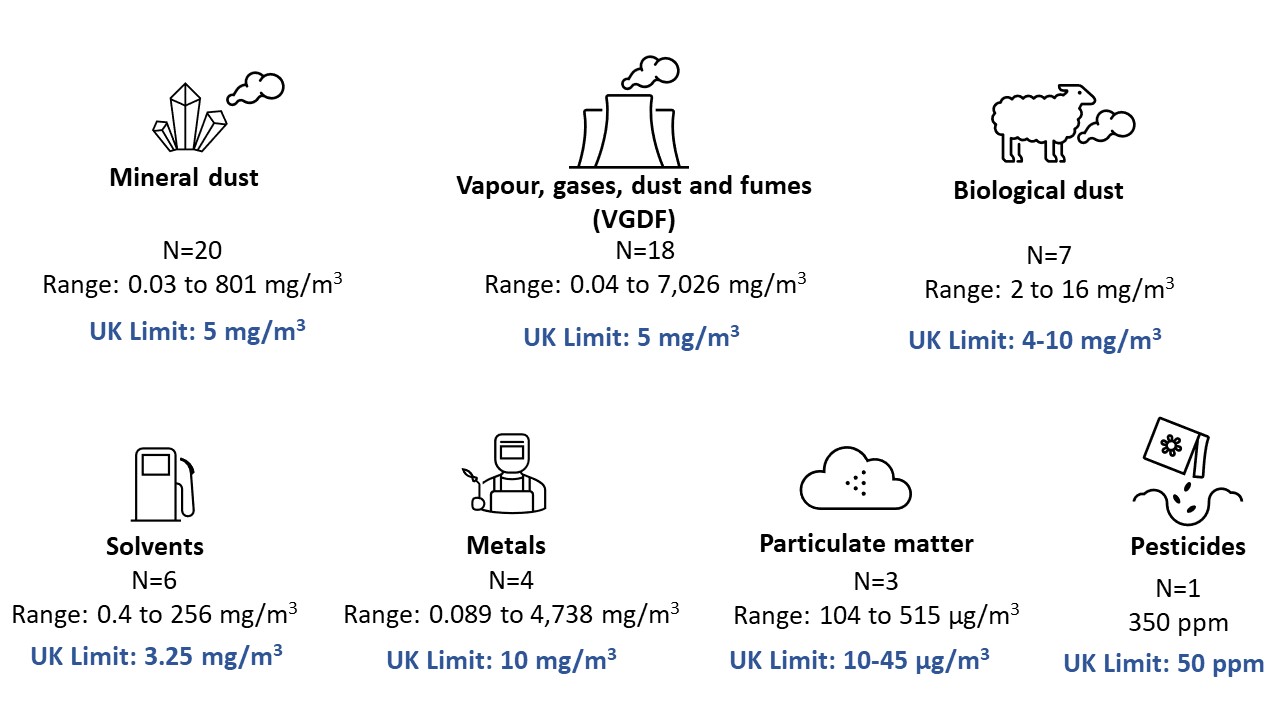

- Workers carrying two copies of the most common allele were more likely to develop SAO when exposed to pesticides, vapours, gases, dusts and fumes (VGDF), or metals, as compared to those with no copy of the common allele and not subjected to these occupational exposures.

In other words, some genes appear to amplify the harmful effects of occupational exposures.

Clues from lung tissue

Two genetic variants (rs9273529 and rs644045) were also moderately linked to gene expression in lung tissue, hinting at potential biological mechanisms. These may help explain how occupational and environmental agents trigger inflammation and damage in the lungs in some individuals but not all. However, future research is needed to confirm this.

Why is this study important?

Our findings highlight the complex interplay between genes and environment in determining who develops SAO. Recognising these interactions could help identify workers who are more vulnerable to certain exposures and guide targeted prevention or monitoring strategies. However, this must be used ethically and responsibly. The path to better lung health lies not only in reducing harmful exposures but also in understanding how genes affect lung health.

Read Genes, Jobs, and Lungs: The Hidden Interplay Behind Respiratory Health in full