by Michelle Lin, MRes Student in the Department of Life Sciences

Cryptococcosis: The Silent Killer

The young patient presented to the hospital with a fever, headache, seizures, and both eyes bulging out of their sockets. Suspecting an infection, doctors first treated the boy with a common antibiotic, Penicillin, presumably to knock out whatever bacterial agent they believed was causing his symptoms.¹

With the boy’s condition failing to improve, doctors kept the boy hospitalized as they searched for a diagnosis and administered various antibiotic and antiviral medications.

As his hospital stay dragged on, the boys condition continued to deteriorate until, after 52 days of ineffective treatments in the hospital, the boy succumbed to his illness. Post-mortem, doctors were able to confirm the boy had been suffering from cryptococcosis, an invasive fungal infection that, without proper anti-fungal treatment, is almost uniformly fatal.

He was six years old.

——————————————————————————–

A fungal infection?

Pathogenic fungi (meaning they are disease causing) are the silent killers of the emerging infectious diseases. Rarer than bacterial and viral infections, invasive fungal infections are often overlooked as a major cause of mortality, while still accounting for approximately 1 million deaths a year.²³ The fungal infection that killed the young boy described above, cryptococcosis, is one of these “silent killers.” Caused by two species of fungi commonly found in the environment, Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii, cryptococcosis is responsible for upwards of 181,000 deaths per year.⁴

How does infection occur?

Acquired through exposure in the environment, infection can occur years after the initial inhalation of airborne Cryptococcus particles. After traveling through the respiratory tract, these spores settle in the lungs and from there can infect virtually any organ in the body, with the most common targets being the brain, heart, eyes, and lungs. While cryptococcosis infections can be seen in patients with healthy immune systems, the majority of cryptococcosis cases occur in “immunocompromised” populations. ⁵

Yikes- so what is there to do?

With low- and middle-income countries disproportionately affected by cryptococcosis, disease prevention is often the most sensible public health strategy available.⁶ Knowing where Cryptococcus is in the environment gives public health officials the ability to set guidelines for where vulnerable individuals should avoid going and could even prove beneficial for patients by factoring high-risk locations into the differential diagnosis pipeline. The faster a diagnosis is reached with cryptococcosis the better, as timely delivery of anti-fungal medications can be the difference between life and death.

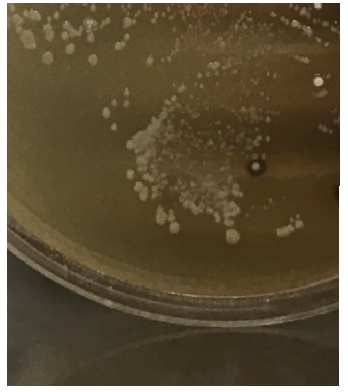

However, all of this requires knowing where C. gattii and C. neoformans are in the environment. That’s where my research comes in. Using field work, statistical modelling, and GIS, I map where in the environment Cryptococcus could be found.

By modelling known presence locations and environmental variables, we are able to uncover the environmental factors most important to each species’ geographic spread and can even create predictive maps depicting where Cryptococcus might be lurking.

By highlighting environmental reservoirs of infection, we are able to determine areas that pose a higher risk of disease transmission in the hopes of one day reducing infections and preventing premature deaths from this environmental scourge.