Pay for performance programmes are being adopted in a growing number of countries as a quality improvement tool. In 2004, the United Kingdom introduced the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) which primarily aimed to improve the management of common chronic conditions, such as diabetes and stroke, in primary care. The Department of Health in England is now considering allowing more flexibility in local pay for performance schemes, such as the introduction of higher payments for meeting tougher performance targets.

Research carried out at Imperial College London suggests that such local pay for performance schemes can improve target achievement by general practices but have no significant impact on the overall quality of clinical care. The study was funded by the NIHR and the NW London Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) and published in the journal PLoS One.

In the study, which was carried out by a team from the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at Imperial College London, the impact of a local pay for performance programme (QOF+), which rewarded financially more ambitious quality targets (‘stretch targets’) than those used nationally in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) was examined. The research team focused on targets for intermediate outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The team also analysed patient-level data on exception reporting. Exception reporting allows practitioners to exclude patients from target calculations if certain criteria are met, e.g. the patient has a terminal illness or gives informed dissent from treatment.

The team found that the local pay for performance program led to significantly higher target achievements for the management of hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes and stroke. However, the increase was driven by higher rates of exception reporting in patients. There were no statistically significant improvements in mean blood pressure, cholesterol or HbA1c levels. Thus, achievement of higher payment thresholds in the local pay for performance scheme was mainly due to increased exception reporting by practices. This may have been because the patients who were not exception-reported would not have benefited from more intensive treatment. There were no significant improvements in overall quality of clinical care once exception reporting was taken into account.

Hence, active monitoring of exception reporting should be considered when setting more ambitious quality targets for primary care teams. Some policy-makers and health service managers may consider giving practices less scope to exclude patients from pay from performance targets in an attempt to improve quality of care. Conversely, pay for performance programmes should not encourage over-treatment or inappropriate treatment; and exception reporting of suitable patients should always be allowed. Patients should also always be fully involved in decisions about their care and decide whether the incremental benefits of more intensive treatment will outweigh the potential problems (for example, from more intensive control of glucose in people with diabetes).

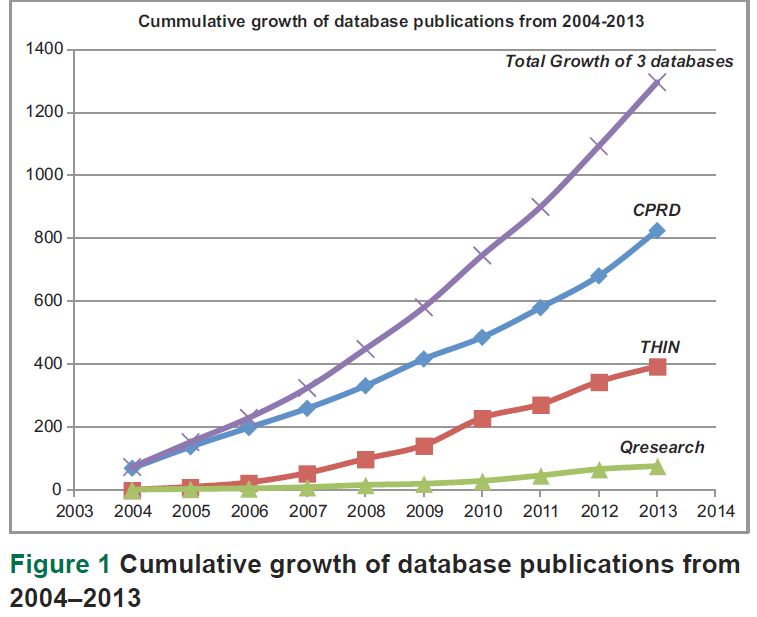

Data collected in electronic medical records for a patient in primary care can span from birth to death and can have enormous benefits in improving health care and public health, and for research. Several systems exist in the United Kingdom (UK) to facilitate the use of research data generated from consultations between primary care professionals and their patients.

Data collected in electronic medical records for a patient in primary care can span from birth to death and can have enormous benefits in improving health care and public health, and for research. Several systems exist in the United Kingdom (UK) to facilitate the use of research data generated from consultations between primary care professionals and their patients.