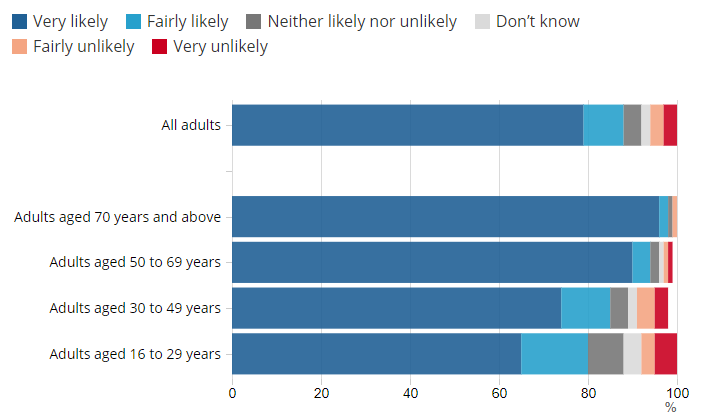

Vaccination offers the UK the best exit strategy from the covid-19 pandemic. [1] To accomplish this objective, achieving high population coverage of covid-19 vaccination is essential. However, despite the good safety and efficacy of covid-19 vaccines, public scepticism about the vaccines persists. [2] Vaccine opposition has existed for as long as vaccinations and, despite the public’s increasing scientific sophistication, has been growing across high-income countries, leading the WHO to list it in the top 10 global health threats in 2019. [3,4] In the UK, the covid-19 vaccination programme continues to gather pace, giving the UK a rare pandemic win; however, those prioritised for vaccination represent groups with low vaccine hesitancy rates. There have been many surveys assessing covid-19 vaccine hesitancy. Potentially affecting as many as one in three individuals in the UK, vaccine hesitancy is pervasive, especially amongst young adults and ethnic minorities, threatening to undermine the pandemic response. [5-7] To avoid disrupting the vaccination programme’s success, developing strategies that address vaccine scepticism is essential.

To dispel vaccine misinformation and myths, differentiating between the under-vaccinated, the anti-vaxxers, and the vaccine-hesitant is required. The vaccine-hesitant represent those who are uncertain about getting vaccinated, but remain open to it if they are convinced that vaccines are safe, effective, and necessary. In the vaccine-hesitant, it is essential to differentiate between vaccine-associated misinformation and mistrust.

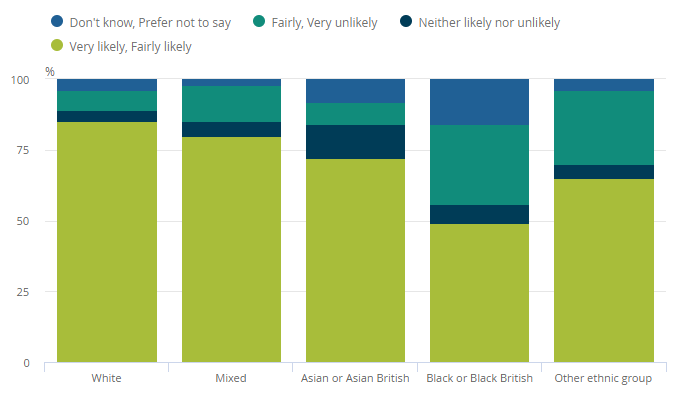

A recent survey carried out by the Royal College of General Practitioners demonstrated that people of Black, Asian and mixed ethnic backgrounds are 53%, 36% and 67% less likely to have been vaccinated when compared to their white counterparts. [8] In the US, 32% of Black adults would definitely, or probably, get vaccinated if made available at no expense, compared to 52% of White adults. [9] While these communities are not ill-informed regarding their heightened risk of severe illness and death from covid-19, hesitancy in ethnic minorities remains disproportionately high. [9] Mistrust felt by this population is not irrational and must be addressed with respect. In addition to a history of systemic racism, which affects many Black people globally, the pandemic has allowed mistrust of covid-19 vaccines to thrive; as stated by the WHO, “racist remarks”, including French doctors suggesting Africa should be a testing ground for coronavirus, are not helpful and this “colonial mentality has to stop.” [10] In the UK, 90.6% of covid-19 vaccine recipients are white. [8] To avoid increasing the health inequalities that covid-19 has harshly exposed, engaging with vaccine-hesitant subgroups is required to increase knowledge levels, reduce perceived risks, and enable informed decision-making. Enhancing vaccine access and convenience will also improve support for vaccination. [11]

As real-time evidence continues to emerge, and mass vaccination campaigns approach vaccine-hesitant groups, culturally sensitive and tailored risk communication and messaging, co-involving faith and influential community leaders, are required to continuously inform, update, and reassure the public. [12] Covid-19 vaccines are unlikely to be made mandatory. Nudging individuals, through choice-offering strategies, incentivises vaccination, and aligns intention with actions. [13] Scientists proactively listening to concerns of subgroups and sharing risks and benefits in a manner that does not impose, but persuades, will improve voluntary cooperation. [13] As there are genuine concerns regarding their record-breaking timescales, alleviating uncertainties about vaccine safety and efficacy is essential. Communicating carefully that their development has followed the same legal requirements for pharmaceutical quality, safety, and efficacy as other medicines, and circulating accurate information including how advances in Ebola, whooping cough, rabies, human papillomavirus and hepatitis A and B vaccine technologies were leveraged for covid-19 vaccine development is important. [14,15]

The availability of online anti-vaccine narratives represents the leading cause of the rise in vaccine hesitancy; accessing these platforms for five to ten minutes increases the perception of risk of vaccines and reduces the perception of risk of refusing vaccines and intention to vaccinate. [16,17] While a number of the “next generation” covid-19 vaccines are based on sequence information, as opposed to “classical” virus- or protein-based vaccines, these vaccines are built on years of developments in infrastructure, knowledge and technical capacity. [18] Removing seeds of doubt requires filling information voids through carefully-designed health surveys, observational qualitative research and social media listening that avoid information overload and the unintentional generation of misinformation through, for example, multiple-choice questions that can lead respondents to misremember false responses as correct. [19,20] Additionally, addressing science-based uncertainty and reduced confidence in public health requires clear communication about the science and building trust through community outreach, respectively. [19]

Drugs, including vaccines in vials, remain useless unless people take them. The WHO’s 10-year Blue Nile Health Project, in Sudan, demonstrated limited success of mass drug administration and confirmed that a holistic and sustainable approach, inclusive of political commitment, community engagement and socioeconomic development, are all required for disease control. [21] The 2009-2010 H1N1 pandemic also demonstrated that vaccine communication efforts were a big challenge and increasing public compliance and confidence in governments and medical facilities depend on coordinated efforts. [22-23]

Vaccines stand at the crossroad between an individual’s decision to accept an intervention and the public health benefits achieved when uptake is sufficiently high. At a time when unity is crucial, additional strategies are required to reach diverse communities, build civic awareness, develop a sense of collective purpose and, ultimately, arm the population with the information needed to defeat covid-19, the latest vaccine-preventable disease we face.

Tasnime Osama, Honorary Clinical Research Fellow, Department of Primary Care & Public Health, Imperial College London

Azeem Majeed, Professor of Primary Care & Public Health, Department of Primary Care & Public Health, Imperial College London

This article was first published by BMJ Opinion.

References

- Majeed A, Molokhia M. Vaccinating the UK against covid-19. BMJ. 2020; 371 :m4654. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4654

- Markovitz G, Russo A. Survey Shows Rising Vaccine Hesitancy Threatening COVID-19 Recovery. World Economic Forum. 2020. https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/11/survey-shows-rising-vaccine-hesitancy-threatening-covid-19-recovery/

- Wolfe RM, Sharp LK. Anti-vaccinationists past and present. BMJ. 2002;325(7361):430-432. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7361.430

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- Savage M. One in three ‘unlikely to take Covid vaccine’. The Guardian. 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/06/one-in-three-unlikely-to-take-covid-vaccine

- Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) weekly insights: latest health indicators in England, 18 December 2020. 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19weeklyinsights/latesthealthindicatorsinengland18december2020#preventative-measures-and-vaccine-attitudes

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine uptake among minority ethnic groups. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/952716/s0979-factors-influencing-vaccine-uptake-minority-ethnic-groups.pdf

- Royal College of General Practitioners. GPs call for high-profile campaign backed by faith leaders and prominent figures from BAME communities to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake. 2021. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/about-us/news/2021/february/gps-call-for-high-profile-campaign-backed-by-faith-leaders.aspx

- Tyson A, Johnson C, Funk C. U.S. Public Now Divided Over Whether To Get COVID-19 Vaccine. Pew Research Center. 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/17/u-s-public-now-divided-over-whether-to-get-covid-19-vaccine/

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 virtual press conference – 6 April, 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-06apr2020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=7753b813_2

- Thomson A, Robinson K, Vallée-Tourangeau G. The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34(8):1018–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065

- UNICEF. Partnering with Religious Communities for Children. 2012. https://sites.unicef.org/about/partnerships/files/Partnering_with_Religious_Communities_for_Children_(UNICEF).pdf

- Dubov A, Phung C. Nudges or mandates? The ethics of mandatory flu vaccination. Vol. 33, Vaccine. 2015;33(22):2530–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.048

- European Medicines Agency. COVID-19 vaccines: key facts. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/covid-19-vaccines-key-facts

- Wellcome. What different types of Covid-19 vaccine are there? 2021. https://wellcome.org/news/what-different-types-covid-19-vaccine-are-there

- Vivion M, Hennequin C, Verger P, Dubé E. Supporting informed decision-making about vaccination: an analysis of two official websites. Public Health. 2020;178:112–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.09.007

- Betsch C, Renkewitz F, Betsch T, Ulshöfer C. The influence of vaccine-critical websites on perceiving vaccination risks. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):446–55. doi: 10.1177/1359105309353647

- van Riel D, de Wit E. Next-generation vaccine platforms for COVID-19. Nat. Mater. 2020;19: 810–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-020-0746-0

- MacDonald NE, Dubé E, Greyston D D, Graham JE. Beware the public opinion survey’s contribution to misinformation and disinformation in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Canvax. 2020. https://canvax.ca/brief/beware-public-opinion-surveys-contribution-misinformation-and-disinformation-covid-19

- Roediger HL, Marsh EJ. The positive and negative consequences of multiple-choice testing [Internet]. Vol. 31, J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2005;31:1155–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.31.5.1155

- Amin M, Abubaker H. Control of schistosomiasis in the gezira irrigation scheme, Sudan. J Biosoc Sci. 2017;49(1):83–98. doi: 10.1017/S0021932016000079

- Schnirring L. H1N1 LESSONS LEARNED Vaccination campaign weathered rough road, paid dividends. Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. 2010. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2010/04/h1n1-lessons-learned-vaccination-campaign-weathered-rough-road-paid

- Mesch GS, Schwirian KP. Social and political determinants of vaccine hesitancy: Lessons learned from the H1N1 pandemic of 2009-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1161–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.031

Read How can we address Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccine acceptance? in full