The primary purpose of general practice electronic health records (EHRs) is to help staff deliver patient care. In an article published in the British Medical Journal, Lara Shemtob, Thomas Beaney, John Norton and I discuss the need for the general practice staff entering data in electronic health records to be more connected to those using the information in areas such as healthcare planning, research and quality improvement.

Documentation facilitates continuity of care and allows symptoms to be tracked over time. Most information is entered into the electronic record as unstructured free text, particularly during time pressed consultations. Although free text provides a mostly adequate record of what has taken place in clinical encounters, it is less useful than structured data for NHS management, quality improvement, and research. Furthermore, free text cannot be used to populate problem lists, calculate risk scores, or feed into clinical management prompts in electronic records, all of which facilitate delivery of appropriate care to patients.

Creating high quality structured data that can be used for health service planning, quality improvement, or research requires clinical coding systems that are confusing to many clinicians. For example, coding can seem rigid in ascribing concrete labels to symptoms that may be evolving or of diagnostic uncertainty. It is time consuming for staff to process external inputs to the electronic record, such as letters from secondary care, and if this is done by administrators, comprehension of clinical information may be a further barrier to high quality structured data entry.

The content of digital communications such as text messages from patients to clinicians, emails, and e-consultations may also need to be converted to structured data, even if the communication exists in the electronic health record. This all represents additional work for clinicians with seemingly little direct incentive for patients. As frontline clinical staff are usually not involved in the secondary uses of data, such as health service development and planning, they may not consider the extra work a priority.

To maximise the potential of routinely collected data, we need to connect those entering the data with those using them, also incorporating patients as key beneficiaries. This requires adopting a learning health systems approach to improving health outcomes, which involves patients and clinicians working with researchers to deliver evidence based change, and making better use of existing technology to improve standardised data input while delivering care.

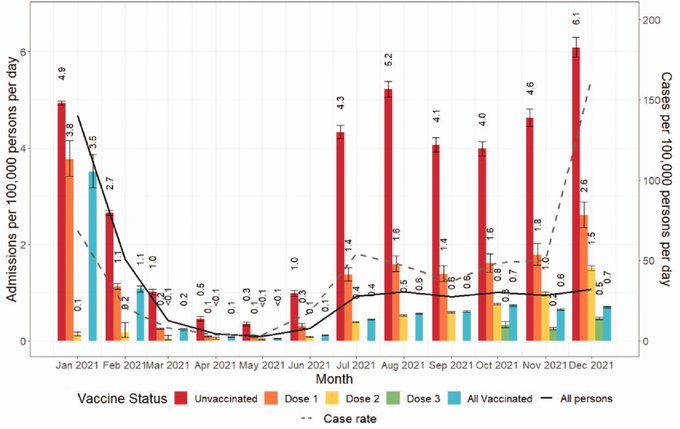

Data from primary care played a key role in the UK’s Covid-19 pandemic response as shown in this slide which uses data from a range of sources – including general practice records – to examine the impact of vaccination on hospital admissions for Covid-19 in England.