- My Imperial Global Development Fellows Fund Placement at Imperial

- Researchers and community members working together to shape research on respiratory infections in young children

- HOPE for Hand Osteoarthritis

- Having an Impact with Public Involvement in Paediatric Intensive Care Research

- Public engagement and involvement at the Cardiomyopathy UK conference: When researchers and the public meet

Dr Toby Athersuch, Lecturer, Phenome Centre

‘Frontiers in Cystinuria Research’ was an event held last October at Imperial College London. It involved people affected by cystinuria in discussions with expert medical professionals and academic researchers active in this area. The aim of the event was to capture some of these rich patient experiences to inform future precision medicine research, while simultaneously providing a forum for patients to share their insight. We feel that these types of event are important enablers of patient-directed research development, particularly relevant in the context of rare metabolic diseases, where patient input and advocacy is often underrepresented.

What is Cystinuria?

Cysteine is an amino acid, which is a ‘building block’ of protein in the body. People affected by cystinuria (a rare, genetic condition) have difficulties transporting cysteine into the kidney, which results in the development of kidney stones. Cystinuria involves complex disease management (both lifelong and continual lifestyle changes) which means that there are many factors that can influence a patient’s quality of life.

Tell us more about the ‘Frontiers in Cystinuria Research’ event

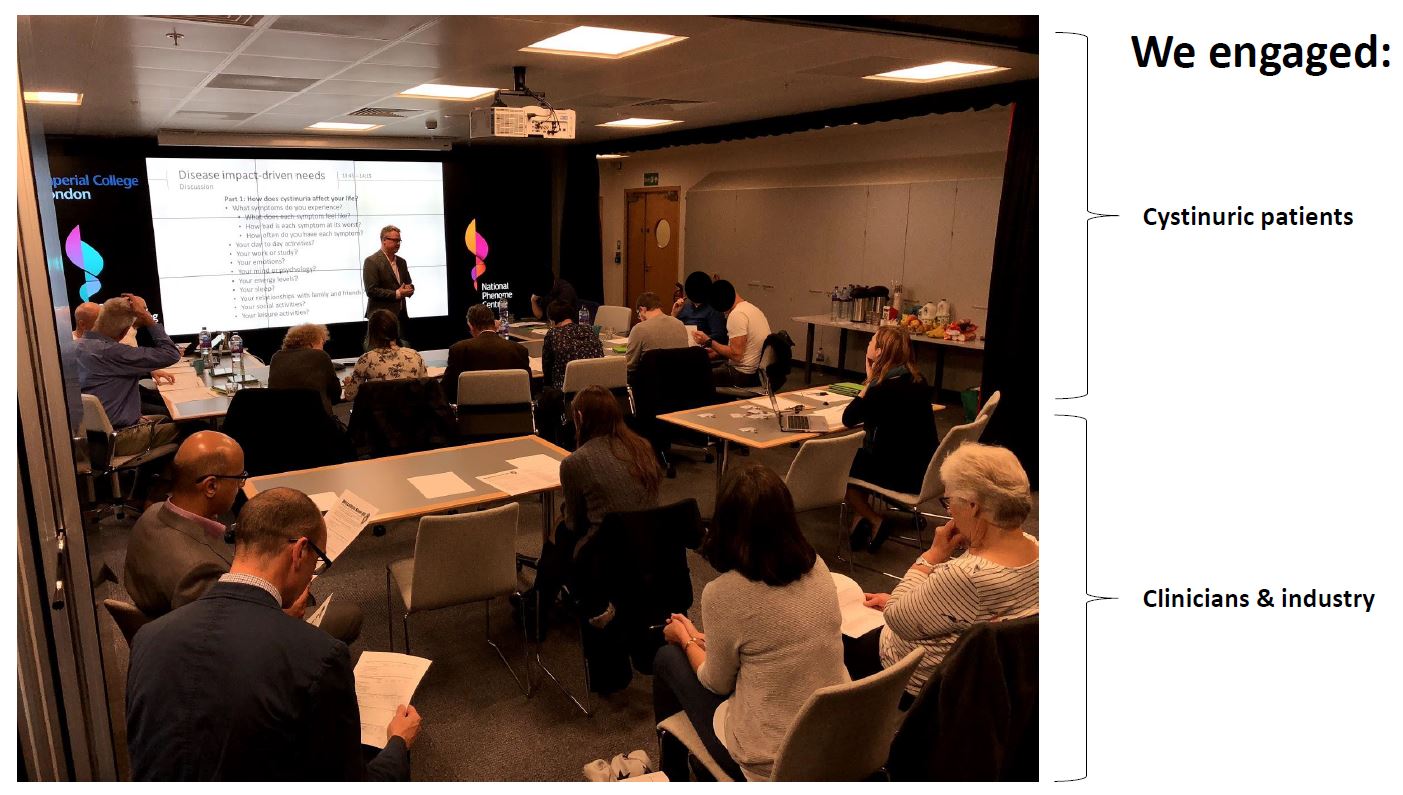

The event was delivered by Imperial researchers (Dr Matthew Lewis, Mrs Kathy Lewis, Dr Toby Athersuch) as well as primary care healthcare professionals, and research experts in pharmaceutical development for improved management of cystinuria. To start the event, we delivered an introductory information session that outlined the current status of cystinuria research and disease management. The second session was a discussion forum that explored unmet need for people living with cystinuria. This provided an opportunity for attendees to voice their own views/opinions on the suitability of research tools that currently exist (as discussed in the first session) as well as an opportunity to reflect on how individuals manage their own diet and lifestyle, which are major contributors to their disease management.

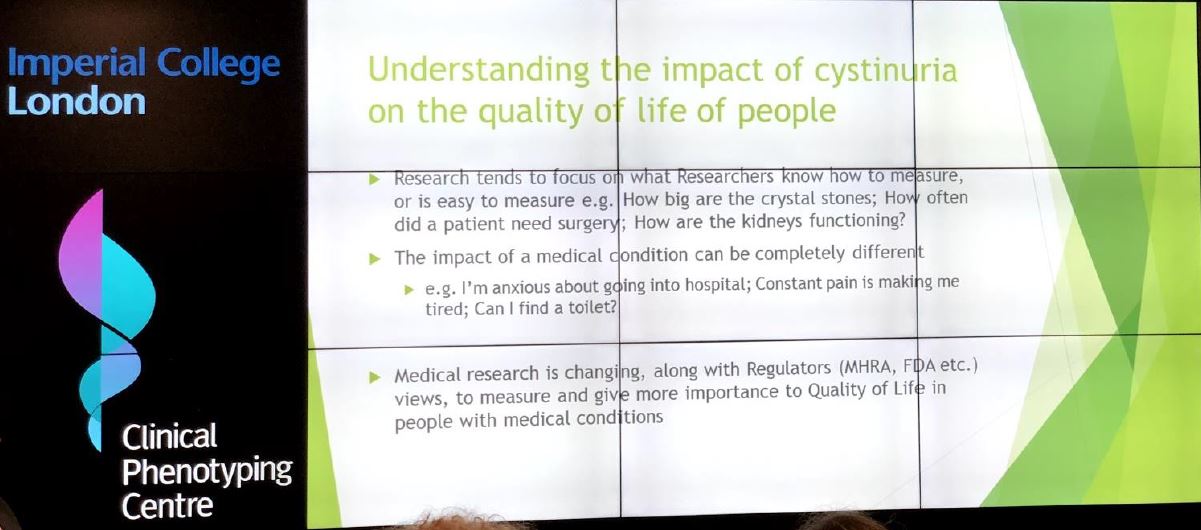

Subsequent sessions focused on establishing attendees’ views on the suitability of currently used (largely generic) Quality-of-Life (QoL) questionnaires, specifically on how well patients felt they captured important aspects of their own lives that were influenced by management of their condition. Finally, the group discussed together aspects of clinical study design for metabolic phenotyping studies (analysing biofluids such as blood and urine to build up a detailed picture about their biochemical makeup, that complements genetic information). This included a discussion on biosample collections, and which would be most or least accepted and/or feasible.

What were you trying to achieve?

Our starting point for this public involvement activity was capturing and responding to the opinions of people affected by cystinuria to provide important additional context when assessing options for future directions our own research, centred on improved patient care through precision medicine. We anticipated that the event would lead to a more complete and patient-informed perspective to guide our research. We also hoped that it would provide greater insight to potentially unknown or underexplored health outcomes which require further research (e.g. drug side effects and/or people living with more than one chronic condition), as well as feedback on the design/feasibility of biosample collection methods.

Who did you involve and how did you find the right people?

People living with cystinuria, particularly in London, have a strong interest in and are engaged with outreach and educational opportunities related to their care. Furthermore, the chronic nature of cystinuria, which is currently managed through substantial lifestyle changes, dietary restrictions, and life-long drug therapy mean that people affected by cystinuria can offer insight about aspects of their care which are most important to their quality of life.

We approached London-based medical practitioners who were experts and active in managing patients with cystinuria and invited them to attend as supporters of the event and to contribute to the discussion and/or information session. These individuals were encouraged to pass on information to their patients as part of the targeted recruitment of people living with cystinuria. We set up an online registration portal; the event was restricted to people affected by cystinuria, including carers. We also confirmed that the NIHR INVOLVE guidelines would be followed for payment of people’s time and expenses however our subsequent discussion with patients revealed that covering travel costs and time input was appreciated but not essential for their attendance.

PharmaKrysto, a pharmaceutical company, were also represented and provided a key update relating to their current therapeutic development initiatives but did not design the programme or lead the discussion. The event was funded by both PharmaKrysto and a NIHR Imperial BRC PPI Grant.

Were the people you involved given any training?

We provided a short session on the known cause of the disease, and an overview of current research efforts and developments in disease treatment and management. This included input from Imperial academics, leading medical practitioners/specialists, and clinical researchers involved in therapeutic development. No other specific training was provided before or during the event, but several attendees had participated in events involving cystinuric patients and/or related research before.

Did you achieve what you set out to do?

Overall, the main objectives of the event were achieved. In brief these were:

• Attendees to receive education related to the current state of research in their disease area

• Provide an opportunity for people affected by cystinuria to openly discuss unmet need of patients that remains unaddressed by the clinical and research communities

• To allow attendees to aid the identification and prioritisation of the direction of future research in this area, allowing for the emergence of observations made by people affected by cystinuria, as well as questions and concerns

• To discuss the design and management of patient sampling for a future clinical trial – e.g. practical considerations and likely study protocol adherence issues

What impact did the PPI have on the people involved?

The Imperial organising group were all encouraged – but not surprised – by the enthusiasm for the event among people affected by cystinuria. Several attendees travelled a long way to attend (South Coast / North England) on a day with poor weather conditions and major travel disruption. This reconfirmed, at least anecdotally, that people living with cystinuria and their carers are very keen to support efforts that can help treat/manage their condition.

The event clearly had an impact on the attendees; we received several messages of thanks and many attendees were keen to know of future public involvement or research activities in which they could participate.

One common theme from the comments on the day was that attendees were glad to have an opportunity to meet with others living with cystinuria, and have the opportunity to openly discuss their own experiences and disease management. The rarity of the disease means that few people affected by cystinuria (outside of London particularly) have any organised support group networks and medical advice is often inadequate. The event raised some key points such as:

• Awareness of key scientific/clinical aspects of the disease and participation in discussion were both high among our group of volunteers.

• Cystinuria is a specific condition with specific challenges – current generic Quality of Life questionnaires not well suited for evaluation of the rare, genetic condition. For example, people living with cystinuria need to drink considerable volumes of liquid each day, which results in frequent toilet breaks. These are aspects not well covered by the existing tools.

• People living with cystinuria want more frequent feedback about their chronic disease and knowledge of the effectiveness of their treatments (medications or lifestyle changes).

• People living with cystinuria are willing to undergo and follow complex and invasive sample collection procedures if they clearly understand why and how these samples will contribute to research.

• Following the rich conversations which took place at this event we realised the need for a follow-up questionnaire that would appropriately address and capture patient perspectives on designing new studies and an improving Quality of Life questionnaires currently used in cystinuria studies.

What was the most challenging part of doing PPI and how did you overcome it?

The overall event planning, recruitment of attendees and delivery went smoothly. However, we attempted to gather anonymous feedback, during the event by providing each attendee with an iPad to complete an online poll on the website Mentimeter. Unfortunately, while the iPads worked flawlessly, the WiFi connection/logins were a major barrier. On reflection, simply inviting attendees with smartphones to use their own devices would have been easier and less challenging, although this may have meant some attendees were unable to participate on their own smartphone device.

What advice would you give others interested in doing something like this?

One thing that we found to be essential to the success of the event was that we had a clear idea of how the day was structured (i.e. what time we would allocate to the introductory session / training compared with the time we would allocate to discussion). Some advice to others who may be running events with a similar budget would be to:

- Ensure the discussion time is adequate. We had a good balance, yet it was clear that attendees would have been happy to continue discussions for much longer than time/funds permitted.

- Ensure there is an opportunity for all attendees to contribute. There were several individuals in our group who were confident to comment (and this was very welcome), but others less so. We attempted to manage the discussion appropriately (e.g. get people to talk in groups together, foster conversations, provide an opportunity for introductions, etc.) to ensure that views from across the group were heard.

- Ensure the aim of the discussion is clear. We found that explicitly stating that the aim was to inform research helped improve engagement. We believe this is as their comments were framed alongside our efforts to improve research practice and study design / participant adherence to study protocols etc.

So, what’s next?

The group largely agreed that a survey to capture more detail on specific aspects of patient feedback would be welcome. This action will be taken up during 2019-2020 and will feed directly into plans for specific patient research activities on Quality of Life metrics. Based on this input, we will review the need to revise generic Quality of Life surveys used for people living with cystinuria. We will also consider the feasibility of a future research event to undertake a thematic analysis of patient feedback/discussion to help design improved survey instruments for people living with cystinuria.

Given the enthusiasm shown by people affected by cystinuria from far outside London, we discussed the possibility of holding additional public involvement events in other regions (potentially to coincide with other patient day events). This is in order to broaden the reach of the views captured as these will be likely to be different depending on patients’ proximity to key cystinuria-relevant resources/clinicians and to expand on the London-centric nature of our approach to date.