This World Health Day, Jane Bruton reflects on her time as an HIV nurse during the early years of the HIV pandemic, and shares observations relevant to the COVID-19 outbreak today. #SupportNursesAndMidwives

2020 is the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife and this year’s World Health Day (7 April 2020) celebrates the role that these professions play in keeping the world healthy. Both nurses and midwives are at the forefront of the COVID-19 response. And every day, as I read the experiences of nurses on the front line, it takes me back to my time on the ward.

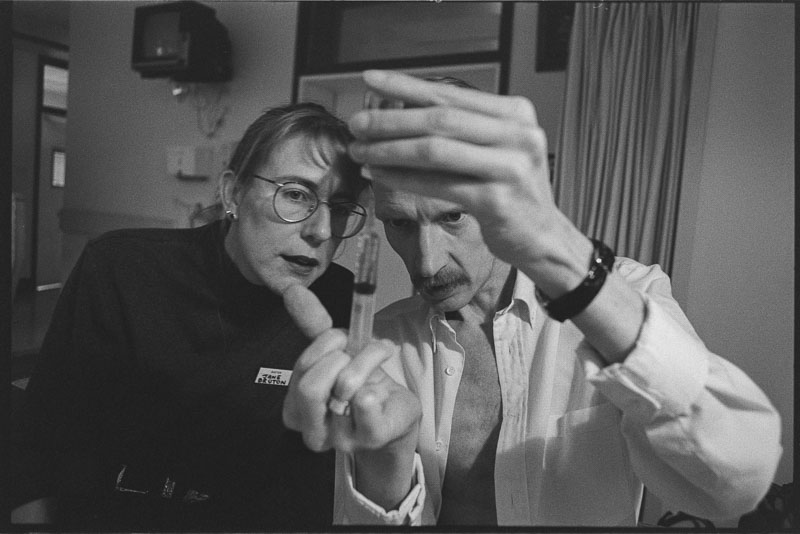

In 1981, thirty-nine years ago, I qualified as a registered nurse in the UK. That same year, the world saw the first reported cases of what became known as AIDS, caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Five years later, I was a ward sister on an infectious diseases ward caring for people living with HIV, and I continued to work in HIV care until 2013.

1981 marked the beginning of a pandemic that has seen 75 million infected and 32 million die. The COVID-19 pandemic is on a different scale and speed from HIV in the 1980s and 90s, but while there are many differences, there are similarities too and lessons from HIV that can usefully be shared.

New model of care

HIV changed the way we nursed. It changed the dynamics within the care team and the relationships with patients and their partner, family and friends. Some of our patients had been rejected by their family or friends because of their HIV. They were vilified in the media. They were all young, usually male, and terminal – albeit at different stages – and they had all lost friends and/or partners with HIV. The old paternalistic medical model was not appropriate for the care they needed, so we developed a non-hierarchical holistic model with the patient at the centre, which is now known as “patient-centred care”.

Yesterday, I read a post on a social media site from a nurse working with COVID-19 patients: she describes how the care team “had never felt so close and supportive” from the consultant to the cleaner. She describes nurses working extra hours to support each other despite their worries. Finally, she talks about how, with scared patients and no family allowed, nurses had to be “more than healthcare workers” for the patient and the family. It felt like I was reading about my ward 30 years ago.

There is, or rather should be, no going back once you have experienced a levelling of the team, valuing each and every role and person on the team, and developing those deeper relationships with patients and family. I say ‘should be’ because we lost some of those gains in the nursing model when new antiretroviral treatments privileged a more medical model approach. Despite this, nurses have continued to develop and promote patient-centred care and value team working.

Fear of contagion

One stark difference between the two pandemics is of course the mode of transmission. COVID-19 has proven to be highly contagious requiring social distancing measures to reduce the risk of infection, and strict infection control measures, including personal protective equipment (PPE), to protect the care deliverers. HIV is a blood borne virus and is not transmitted through social contact.

However, fear of contagion was palpable in the early 1980s when we didn’t know what caused AIDS but thought it was infectious. This led to patients receiving less than adequate care, left in side rooms with staff wearing ‘space suits’ for protection. The media engendered fear in the community. And despite the modes of transmission being fully understood by the mid-1980s it proved hard to break the fear of both health workers and the community. Fear of contagion around people with HIV persists even today.

Stigma

HIV became a stigmatised disease. Some nurses and medical staff volunteered to work on the new specialist HIV wards, and some of them attracted the same sort of abuse and ostracism that people working with COVID-19 are experiencing now. Nurses then and now being spat at or asked to leave their rented homes for fear of contagion. While nurses working with COVID-19 have real fears around infecting family members which is not the case for HIV, there were instances of HIV nurses not being allowed to visit family members through fear of them infecting children, and of friends not wanting to share mugs or cutlery.

Care capacity

The total numbers of HIV patients at any one time were small back then in comparison with the current pandemic, but on a micro level our wards were always full of sick and dying patients. We too had to expand capacity and learn new skills to accommodate the growth in numbers as more people got tested. And then, as now, we had no treatments targeting the virus, only managing other infections and supportive care.

Palliative care

In some senses there was a sense of fighting a losing battle, despite doing all you could; I think it must feel similar on the wards today with COVID-19 patients, even though many do recover. We developed the knowledge and skills to know when to pull back from active treatment and begin palliation, and we had the chance to involve patients in these decisions. The shift to palliative care occurs for COVID-19 too, and is very distressing for staff, patients and families, even though it is something that is regularly addressed in intensive care units, it is rarely so broadly discussed in the media.

Social Media

One interesting difference is the role of social media today through which nurses write or speak out and share their experiences on the front line. You can feel their pain, frustration and compassion, and you see the moments of joy when a patient is discharged. Without social media and with a largely hostile press, the public didn’t get to know what we did in HIV. We only shared our experience within the team.

Time for reflection

It must be hard now for nurses on the front line of COVID-19 work to reflect on what’s happening. All they can do is get through each day, working extra hours, supporting each other, getting exhausted and yet not able to sleep. My experience of HIV is that we only have processed that stuff through documentaries and oral histories in the last 3 or 4 years – three decades later!

Right now, no-one knows when the right time will be to begin reflection. But from my experience in acute HIV, the wounds being inflicted today will run deep. For us, formal reflection, through recording oral histories from nurses and other healthcare workers has been very important. In fact, COVID-19 has prompted another outpouring among many former colleagues of mine on social media, remembering the grief, the need to go that extra mile, the exhaustion, frustration and the laughs.

Some of the grief comes from dealing with multiple deaths in a day, in a week, in a month. The pain the team felt was immense when the family refused to visit or be there when their son was dying. How much more difficult it must be to comfort the family that wants to be there through video or phone link. How difficult it must be to comfort a scared patient when wearing protective clothing.

We started interviewing doctors and nurses about their experience of living through the early days of the HIV crisis in the UK for a number of reasons, not least of which was there was little documented about healthcare workers’ experience. We wanted to pass on what we learnt about how to deal with an unknown, unforeseen epidemic/pandemic. From a nursing point of view, we wanted to share how and why we developed our “patient-centred” model of care, why and how non-hierarchical team working was and is best practice. We have done this in retrospect but with the COVID-19 pandemic together with social media, we can build up and share our experiences and some of the best practices in real time and share with other nurses across the world.

Losing colleagues

One area we found particularly difficult was looking after a nursing or medical colleague who was dying, the impact of the death on the team and particularly for those staff living with HIV wondering if they will be next. There have already been at least seven recorded deaths of nursing and medical staff from COVID-19 and knowing the statistics from Italy this is likely to get worse.

Nurses, if they haven’t already, will end up nursing one or more of their colleagues. The only way we could cope with this was to share the care throughout the team, if possible, and break with our model of primary nursing (caring for the same group of patients from admission to discharge): this way we found the stress was shared. And to allow time for nurses to share their grief and to be offered expert support and help as needed. Psychological care has been built into the provisions at the Nightingale Hospital in London but we know that, in a cash-strapped service, expert support is not readily available on the wards.

Global impact

When HIV was first reported in San Francisco and New York, little attention was paid to the growing problem of AIDS in Sub Saharan Africa where it was referred to as slim disease. We know now that it devastated those countries with high infection and death rates. The burden on the health services, social, political and economic structures was immense. COVID-19 may well have a devastating impact on these countries where social distancing is almost impossible, and it will occur against a backdrop of poverty, ill-health and weak health systems.

As with HIV, nurses will share their experiences and provide support and solidarity across the world and be at the forefront of reducing suffering from this new pandemic.

Written by Jane Bruton

About the author

Jane Bruton is the Clinical Research Manager in the Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC), Imperial College London. She has worked in HIV and Sexual Health for 26 years and has a Masters in Medical Anthropology. Special expertise includes qualitative research, patient involvement in health care and nursing role development. She has conducted and been involved in a number of qualitative studies including; nurse handover, the HIV patient journey, living with and curing Hepatitis C, and parental consent in adolescent research. In Jane’s spare time, she is part of the organising team for “The AIDS era: an oral history of health care workers”, she teaches and supports HIV nurses in Eastern Europe and is a Trustee of Positively UK, a peer-led HIV Charity.