- Reflections

- Public involvement

- Involving children

- Child health

- Involving schools

- Teachers

- Research participation

- Research with children

Supporting schools to participate in research on children’s physical activity and wellbeing

In conversation with: Dr Bina Ram, Postdoctoral Research Associate working within the Child Health Unit, Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London

What did you do?

I am leading the iMprOVE study which is examining physical activity of Year 1 children (aged 5-6 years) in Greater London primary schools. The main aim of the study is to compare differences in children’s physical activity across schools that do and do not implement a school based active mile intervention called (which involves children running or jogging for 15 minutes at least three times a week during the school day), whilst also examining its effect on children’s mental health and educational performance. The Daily Mile is said to make children ‘healthier, happier, and concentrate better in class’. School-based physical activity interventions are not compulsory for schools, but UK government policy recommend this as an easy and accessible way to help children reach recommended guidelines of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per day.

To identify children to involve for this study, we approached and invited schools across London to participate. Over the duration of a year (from 2021), we successfully recruited 41 schools and through them we invited 2,458 children (and their parent/guardian) to take part in the study.

Given the challenges of recruiting schools into research studies, we decided to find out teacher’s views on reasons for participating in our study, and the facilitators and barriers for schools to get involved in child public health research. We also wanted to find out how they viewed the benefits of being involved in research.

What were you trying to achieve?

Through this work we wanted to identify:

-

- how research could be useful for schools (to be able to help us understand how to better engage with schools around research participation),

- the best way to feedback research findings to schools, and

- the facilitators/barriers of being involved in research for teachers and schools.

These insights are valuable to help us to understand how to better engage with schools around research participation and in particular how to translate research findings back to the schools. Additionally, identifying facilitators and barriers of why schools may engage in research will help inform school recruitment in future studies.

Who did you involve and how did you find the appropriate people?

We invited 31 teachers (participants) from schools across London who are participating in the iMprOVE study.

A total of 11 participants (x4 Physical Education (PE) Leads, x2 class teachers, x1 head teacher, x1 deputy head, x1 PE teacher, x1 pastoral and wellbeing lead, and x1 special needs inclusion leader); participants represented 10 schools from 8 London boroughs. The workshops were carried out online via Zoom.

Were the people you involved given any training?

No formal training was required. The workshop facilitators, myself and Esta Orchard who is an expert in public involvement in research, designed and planned the 1-hour workshop which included whole group discussions and two polls for votes outlined below.

Did you achieve what you set out to do?

The discussions provided us with important insight into:

-

- The type of information that would be most useful to teachers participating in the iMprOVE study

- Schools’ preferred method of receiving feedback

- What the schools would like from a research partnership

- What researchers can do to help engage schools with their research

Discussion themes and the outcomes are summarised below:

1. What information would be useful to teachers/schools from participating in the iMprOVE study?

Generally, the teachers were interested in the physical activity levels of the children at their school which we were measuring using robust methodology (i.e., through validated accelerometers). This information would help teachers make decisions on whether there is a need to increase physical activity either through active mile interventions or to extend / offer more PE lessons. (It is important to note that we had approached schools to participate in the iMprOVE study when they had just re-opened during the pandemic in 2021. Teachers expressed a negative impact of the pandemic on children’s physical and mental health; thus our research was timely and welcomed by the teachers to examine the physical and mental health status of the children at their school).

“…especially when we come to trying to target our least active population…up to this point I’ve only ever just sent out questionnaires and like especially younger children, never know if they’re filled out honestly or if they’ve misunderstood.”

There was much discussion around teachers wanting to know how active children are outside of school to be able to engage them in more physical activity inside of school if needed:

“Knowing the difference between active hours [time spent in physical activity] in school and out of school.”

“So it would be useful to have any data that we can give to parents as well, not just to, you know, to use within school, but actually to encourage parents to do more if they can outside of school.”

To increase the activity of children, some teachers expressed that the data would help support them to increase time spent in physical activity at school:

“I think at my school it’d be it would be useful [to have this data] to kind of fight my corner a little bit…some staff are struggling to fit in two hours of PE a week…it’ll be quite useful to kind of go to [back to] my staff and say, look, this is how active our children are… I think it’ll be useful to kind of back me up a little bit whether the data is really positive or whether it shows what we need to improve on that.”

“It would be targeting pupils and saying, well, OK, they these children, boys or girls might need an additional club during the day for them to get their fitness up.”

In addition, teachers said that it would be very useful to have data on the difference of physical activity between girls and boys, and by ethnic group.

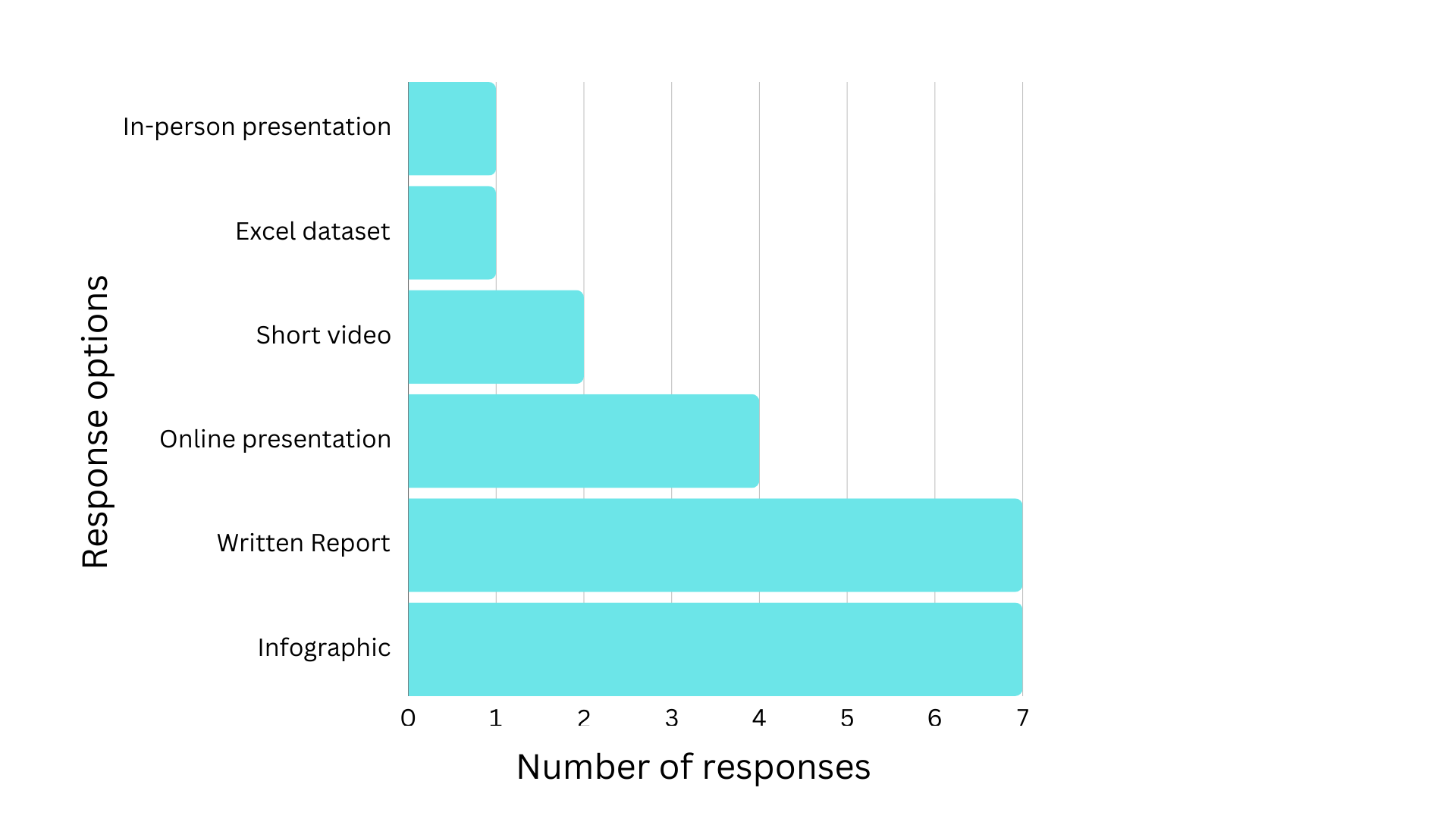

2. What would be the best format to feed this information back?

Collected via online poll (response options provided; participants could select more than one option)

The two most popular ways to feedback the research to schools was by a written report and infographic. They preferred an infographic as a better way of presenting findings to parents with language barriers. The teachers also liked the idea of a simplified online presentation that could be presented to the children and parents who participated in the research.

“So it might be that we have it in two formats…one that we can use as a school and we’ve got quite a large number of ALS [additional learning support] families who would struggle… may be different to what you present or what you provide us with to support parents…”

3. What else would schools like from a partnership programme of research like this?

Teachers said that they can see the value and importance of this research and want to help improve the physical activity of the children at their school, especially as they don’t always have the capacity themselves to examine the health of the children in detail and were therefore particularly keen to get involved. Receiving feedback on the physical activity of the children during the school day was the main motivating factor for their involvement.

“We don’t really get to measure in this way and obviously going forward it would be helpful [to know]”.

“…a useful thing if once we’ve got our data and we know what our data is telling us, we can then brainstorm ideas of like, well, this is what my data tells me.”

We wanted to identify the school’s perspective of what researchers could do to encourage school engagement in research through our second poll.

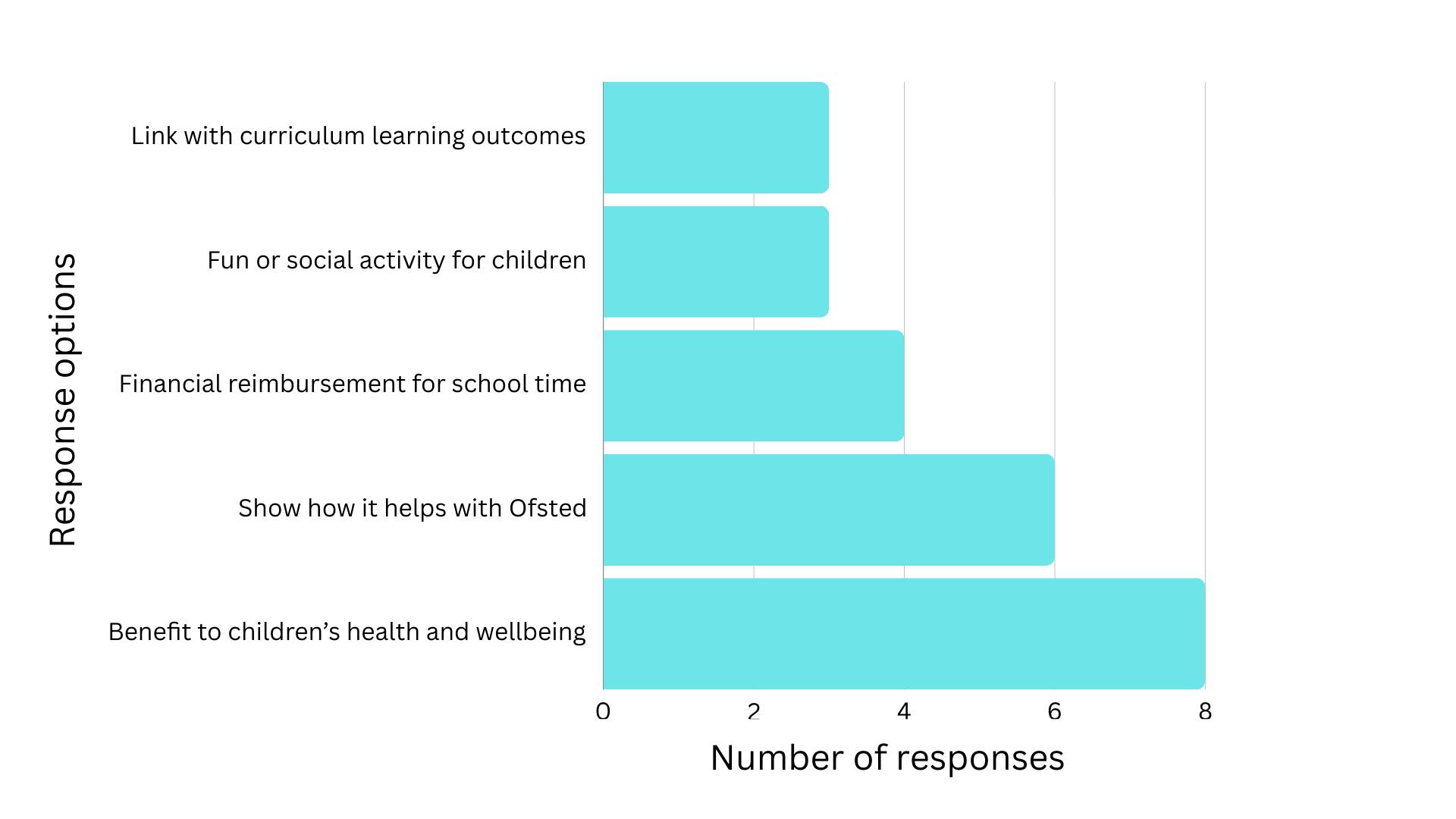

4. What would be the best way to overcome some of the barriers to engaging schools?

Collected via online poll (response options provided; participants could select more than one option)

The two most popular responses were that researchers should demonstrate how their research will benefit children’s health and wellbeing, and how being involved in the research may potentially help with Ofsted expectations (i.e., making it beneficial for the school).

A main barrier of getting involved in research was:

“There’s quite a lot of studies that go on…schools do get bombarded with quite a lot of requests…”

We asked how we could overcome this. Responses included that researchers need to contact the teacher for whom the research is likely to be the most relevant as emails/letters don’t always get passed on. A good way to do this would be for researchers to reach out to the public health teams at the local authorities/councils. They would have the relevant contacts and can also include the study in their newsletters to schools.

We also asked the teachers why they agreed to participate in the iMprOVE study. Most agreed that they wanted to know the health of the children at their school particularly due to pandemic impact. However, they also emphasised our approach – that we took on all the responsibility without adding to teacher workload, and that we were persistent!

“I was so impressed with the fact that you did do all the admin…”

“I think that was the winning thing, that nobody [at the school] had to do anything…and also [liaising] with the parents as well, you did all of that…”

“You were persistent and in the end I thought, well, yes, I’ll do it”.

What impact did the public involvement and/or engagement have on the people?

The teachers who participated in the workshops expressed the importance of our research and how much the children at their schools enjoyed taking part. However, they also expressed that past experiences of being involved in research resulted in not being informed of the findings, and feeling “forgotten” after researchers have collected data from them. They said that using lay language to feedback the results (without the scientific jargon!) is crucial for them to understand the health of the children in their schools, and provides them with an opportunity to review their practices if needed.

What was the most challenging part of doing public involvement and/or engagement and how did you overcome it?

Finding a suitable time for teachers to participate in these workshops was the most challenging. We had initially planned for an in-person workshop, but as the schools were across London, we were mindful of travel times, costs, etc. We therefore opted for an online workshop at a start time of 4pm on a weekday, for an hour, which the teachers agreed worked well. They were also pleased that more than one date was offered to help them fit the workshop around their schedules.

What advice would you give other researchers interested in doing something like this?

Involving schools in research can be very challenging. Targeting the relevant person at the school, providing information about the research in a simplified format, and explaining how it will benefit them are key. Always work around the convenience of the schools and teachers – they will appreciate this! Importantly, school involvement in research does not stop when the data has been collected – schools want to know how their contribution has informed your research and how they can learn from the findings. This will help improve rapport with schools and encourage them to be open to being involved in future research.

So, what’s next?

This workshop is part of the iMprOVE study research. We are analysing the data and aim to provide the participating schools with results from our study, adapting language for schools, children, and parents.