In conversation with: Emily Cooper, Research Associate, Adam Lound, Research Physiotherapist, Patient Experience Research Centre, Imperial College London

What is your research project about and what stage are you at?

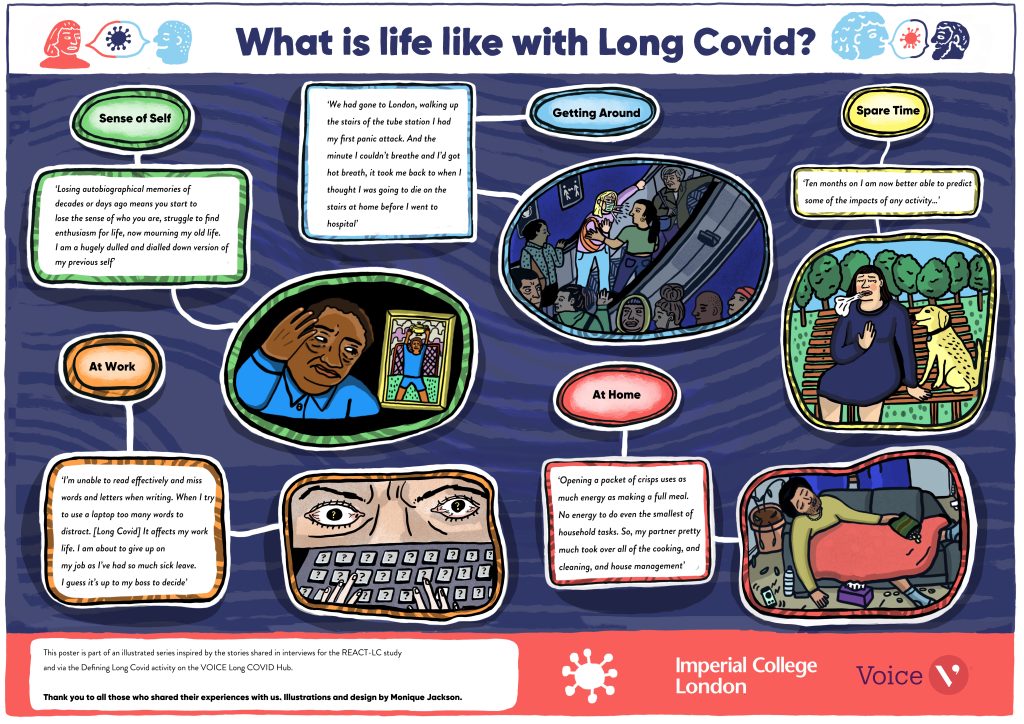

This research project is one part of the REal time Assessment of Community Transmission – Long Covid (REACT-LC) study. The project is a qualitative interview study exploring the different experiences of people with long lasting symptoms after having Covid-19. This study builds on our earlier pilot project, which showed how people experienced different symptoms and whether or not they described this as being ‘Long Covid’. The pilot study highlighted the value of recruiting participants from outside of online support groups, to help better understand the range of different people living with long lasting symptoms. Our early findings revealed big variations in symptom experience as well as differences in awareness of the term ‘Long Covid’ and whether participants felt it applied to them. These findings informed our approach to this larger study.

We are now at the stage of writing up the findings from the current study. Through the project we have explored the variety of ways people living with persistent symptoms in the community manage their illness on a day-to-day basis. We have tried to understand both what people do to manage their symptoms and what factors influence how they do this. We began with a topic guide designed with the help of the public advisors as part of the pilot study. The topic guide asked broad questions about the symptoms people experienced and how these impacted their life. This was then adapted and added to for the main study. We carried out interviews using the guide, which were audio recorded and then written up into a transcript. Once we had all transcripts from the interviews, we analysed them, which involved labelling and grouping the data, then looking for patterns within and between these labels and groups. We have recently written up our findings and shared them with the public advisors.

What did you want patients/the public to help you with?

The REACT-LC Public Advisory Group was brought together in the early stages of the REACT-LC study development. They were involved from the start of the study with the aim of consulting them on each stage of the research. They helped shape data collection and had input into the topic guide and participant information sheet. There were also multiple levels of involvement throughout the data analysis process. We presented our initial impressions from the interviews – this included some key quotes and some topic areas that were most rich in data and asked the group what we should explore in our coding.

The first intention for the analysis of the interview data was to produce a paper on experiences of recovery. This was a topic that was of interest to us (EC and AL) as researchers and one found in the literature but warranted further exploration. We approached the public advisors to discuss this idea and to develop our research question and shape the paper.

Who did you involve and how did you find them?

The REACT-LC Public Advisory Group was brought together at the start of the project in July 2020. Some were existing public partners connected to the REACT studies, others had attended our Let’s Talk About Long COVID event, and some were people with lived experience of Long Covid who were active in the Long Covid community and had already reached out to the project to discuss ways involvement could be improved in Long Covid research. We also included members whose family member or child had lived experience of Long Covid. The public advisory group was made up of six women and three men. Of this group, two had reported pre-existing conditions exacerbated by Long Covid symptoms.

What kind of activity did you undertake to gain insights about your research from public contributors?

Public involvement on this project took the form of ad hoc group discussions, quarterly online public involvement meetings, 1:1 conversations and email-based feedback. For example, we shared the topic guide with the advisory group via email and asked for their comments and feedback. The advisory group read the questions we intended to ask study participants and made suggestions about new topics and different framing of questions, which were incorporated into the final guide. The public advisors suggested including sections of the topic guide that focused on the types of self-management people tried for their symptoms, and their experiences of getting better.

How did your research change as result of the public involvement insights?

In March 2023 the research team held a quarterly meeting with the public advisory group to discuss a potential research question for the main qualitative study, the research team proposed the idea of a paper on ‘recovery’. In the meeting a discussion occurred about the appropriateness of the term ‘recovery’ in the context of persistent symptoms of Covid-19. Some of the advisors felt this was an alienating and unachievable concept for many, who were instead ‘living with’ the condition with little to no hope of getting better. For others in the group, recovery was the only acceptable outcome and ‘living with’ was an unacceptable term that suggested a permanency of their condition.

It became apparent that while the terminology used and the beliefs about the trajectory of the illness experience were different, there was also a common ground where all individuals responded to and managed their symptoms. The focus of the analysis was therefore on understanding the ways participants practically respond to and manage their symptoms, which might be described as the journey of recovery, rather than a state to be reached.

What impact did the Public Involvement have on the people involved?

Members of the public advisory group occasionally fed back the ways the involvement work was impacting them. On reviewing the early findings from the qualitative study one advisor stated:

‘I found it difficult to read and respond to all at once! Especially the fatigue section for me, that really hit hard. Hearing other people’s experiences echoing some of mine was very moving and validating too in a way I guess.’

Another fed back to us on a call that they hadn’t anticipated how emotionally triggering working on Long Covid stories would be, having had their own experience of many of the symptoms reported. We were conscious throughout our involvement activities about the impact of the work on our advisors, both physically and emotionally. We ensured group meetings were at convenient times of day, with breaks and that timelines for completing involvement activities were flexible. We also made sure the group were aware of online Long Covid support groups.

What was the most challenging part of doing Public Involvement and how did you overcome it (or not)?

Sometimes the suggestions from the public advisors were not possible within the scope of the project, for example new interests developed after the initial topic guide design phase and interviews had already taken place meaning we couldn’t collect new data on a new interest area.

During the qualitative analysis phase researchers were deep in the data and struggled to ‘come up for air’ enough to keep advisors updated. This links to another challenge; the project public involvement budget limited what activities we could do, ideally, we would have had a public advisor working with us on analysis to coproduce findings.

What advice would you give other researchers interested in doing something like this?

-

- ensure adequate budget for public involvement,

- set up quarterly advisory group meetings from the start so that updates do not have to be organised and planned during intense phases of work,

- involve public advisors in the study design as well as throughout the study delivery to keep revisiting the focus of the study.

So, what’s next?

We plan to share our findings in the next quarterly public advisory group meeting to gain feedback and input into the write up. We also plan to hold an engagement event with Long Covid clinicians and people with lived experience to discuss how the findings might influence practice.