In this blog post, Dr Kirsten Bell, Senior Research Fellow in Anthropology in the Patient Experience Research Centre, Imperial College London, shares the results of our interactive stall ‘You and Your Health Data’.

This year at the Great Exhibition Road Festival, the Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC) hosted a stall called ‘You and Your Health Data’. Moving beyond routine health data collected by the NHS, we were interested in exploring public attitudes towards sharing health data of different types: research data, data from health apps, and internet browsing data. Each of these types of data either directly or indirectly provide valuable insights into people’s health.

While research data from health studies are the most obviously valuable, health apps provide a wealth of information about things like people’s patterns of physical activity, dietary intake and weight – if you so desire, you can even track your ovulation and menstruation patterns! Likewise, online browsing data provides an intimate picture of your health practices and concerns, not just because of our growing tendency to use ‘Dr Google’ to diagnose health conditions, but because of the consumer sites we constantly browse for goods and services.

The Data Protection Act of 2018 aims to give UK citizens greater control over how their data are used and shared. Certainly, in the context of university research, there are very strict controls on data privacy. In fact, in our experience, some research participants think these controls are too strict, especially in contexts where they want research data to be shared with their healthcare team. However, when it comes to health apps, most of us don’t read the terms or conditions, and wouldn’t have a clue what third parties can access our data. Likewise, in the context of internet browsing, research suggests that opt-in policies (where people are asked to consent for different types of data usage) actually tend to give consumers less control over their data rather than more. If, for example, you just want to make a hairdressing appointment, most people don’t have the time or patience to go through the dreaded ‘Do you accept cookies from this website?’ question, which often requires you to opt in and out of potentially dozens of different options, most of which you probably don’t understand anyway (e.g., what on earth ‘legitimate interest’ means).

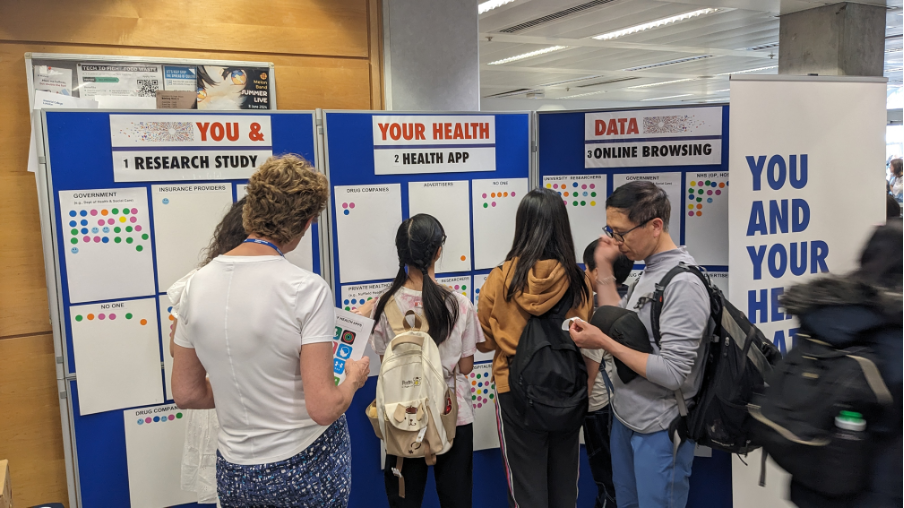

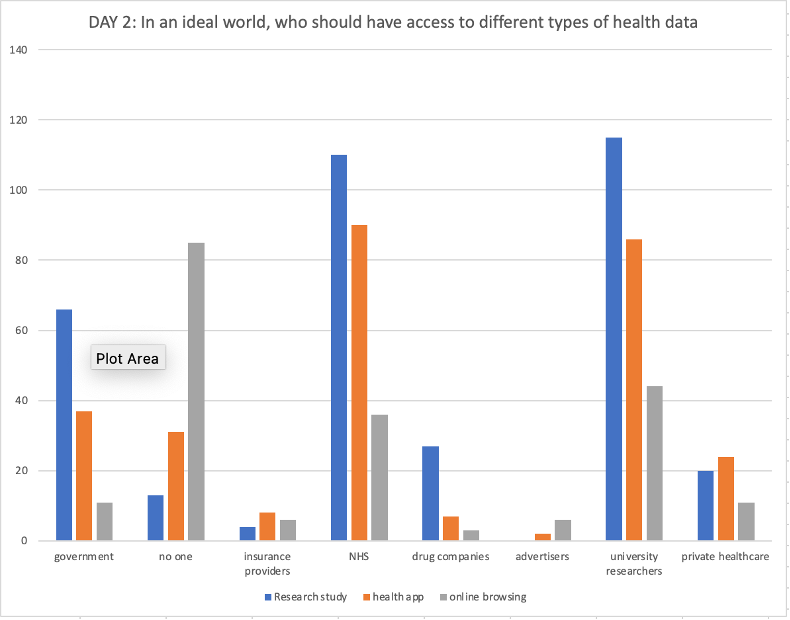

Bearing this in mind, we asked visitors to our stall to imagine who, in an ideal world, they would be interested in sharing their research data, health app data, and internet browsing data with, if they had complete control over what was shared, and with whom. To facilitate these conversations, we conducted an interactive activity where we asked people to place stickers on eight categories of organisations/people they’d be okay sharing this data with. We also asked visitors completing this exercise to fill in a postcard sharing some basic demographic information – age, gender, ethnicity, and education level.

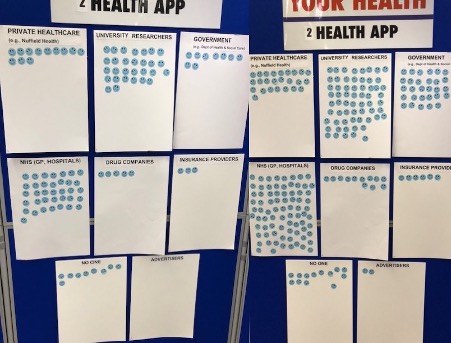

Now, the results of our opportunistic ‘snapshot’ survey are hardly reliable or representative, which is important to bear in mind as we discuss our ‘findings’ below. This activity was more of a conversation starter than a research exercise, especially because patterns in people’s responses were quickly evident to the visitors themselves – and no doubt influenced the way they chose to respond! For example, you can see how the stickers on the ‘health app’ category of data changed over the course of Day 1, from the morning to the afternoon. In the morning, it looked like people were more willing to share health app data with private healthcare providers than with the government, but that picture had changed somewhat by the afternoon.

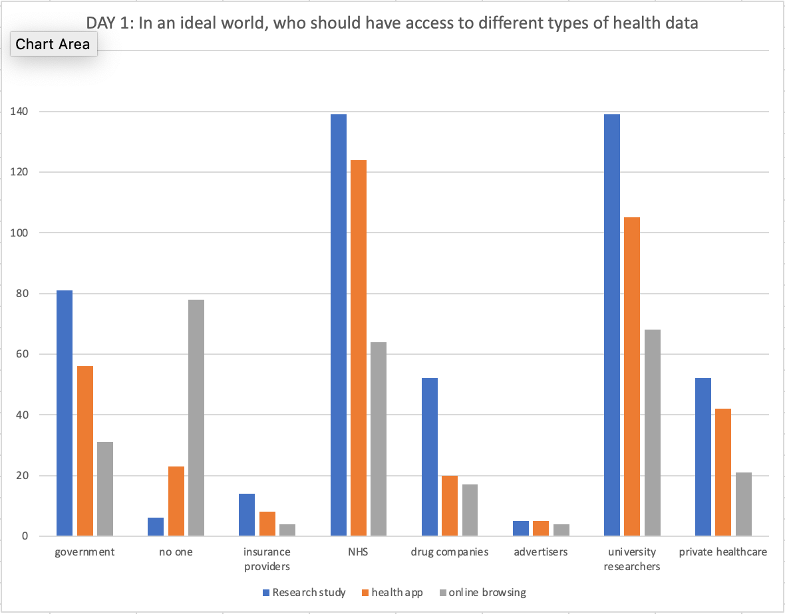

However, the patterns are interesting nonetheless, especially because there were strong general similarities over both days. As you can see below, visitors indicated that they were most willing to share their data with researchers and the NHS – especially their research data and health app data. Notably, they were less willing to share internet browsing data: online browsing data was the only category where ‘no one’ was the most popular option in terms of who visitors would be willing to share it with.

Overall, we were surprised at visitors’ relative openness to sharing health data of different types – including with for-profit organisations such as drug companies and private healthcare providers. That said, insurance providers and advertisers were the least popular options in terms of sharing all kinds of health data. The general pattern seems to be that the more people’s health data might potentially be used against them (for example, to discriminate in insurance provision), the less willing they were to share it – although one person highlighted that health insurance providers are now providing discounts for evidence from health apps regarding high levels of physical activity, which helps to explain why some respondents were willing to share such data.

Overall, our conversations made it clear how complicated this topic is and how difficult it is to consider these questions in the abstract. Numerous people highlighted how contextual their responses were. They emphasised that their willingness to share data would depend fundamentally on the nature of the data in question, whether it was individual-level data or aggregate data and what aspects of their health it related to. For instance, you probably don’t feel the same way about data from a running app than you do about an interview you did for a research study on your sexual health. In fact, one woman, following a lengthy conversation, declined to fill out the activity at all: ‘I don’t know how I feel about it’, she concluded.

People also pointed to the importance of trust and whether organisations – including the government – can be trusted to use data in the ways they say they will, with several people raising concerns about NHS England’s award of a contract to manage NHS data to the US tech company Palantir.

Indeed, one respondent scrawled across his postcard ‘Never trust the government!’ Many people we spoke with raised other examples, such as data breaches within the NHS (like this and this) and firms like 23andMe, along with high-profile cases of data misuse like the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

But it’s important to emphasise that people saw negatives as well as positives to data privacy and security, and highlighted a variety of trade-offs involved, noting that high levels of data privacy can reduce convenience and impede the flow of information where it matters most. For example, various people pointed out the lack of data sharing within the NHS and the ways this impacted care. As one visitor said, extremely high levels of data security can make the data completely unusable, and a ‘balance’ is required between security and useability.

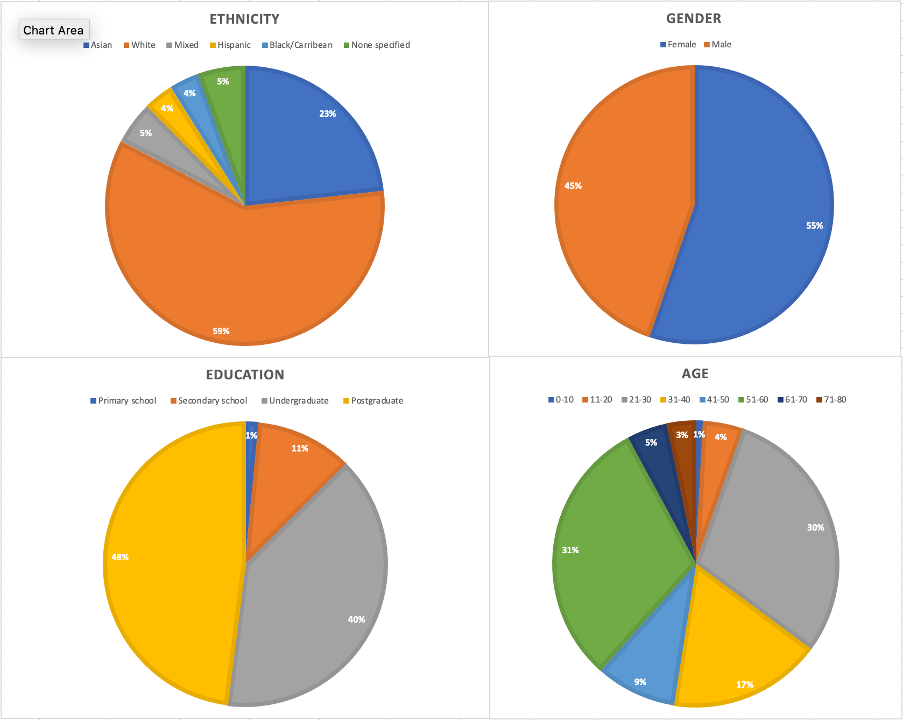

Unquestionably, responses were influenced by the demographic characteristics of the visitors who participated in our activity. Of the 212 people who provided their demographic information (which was about two thirds of the people who visited the stall over the course of the festival), you can see that they are not exactly typical of the UK population: white, highly educated women between the ages of 51-60 dominated the activity.

Probably unsurprisingly, given the characteristics of festival attendees (which included a sizeable proportion of Imperial staff and alumni), a large proportion of university researchers, along with a sizeable minority of respondents with PhDs, completed the activity. As several of the visitors to the stall noted, it therefore probably isn’t a coincidence that so many respondents were willing to share their data with university researchers! We also noticed that people working in marketing and advertising were more likely to think that data should be shared with advertisers, and people working in the pharmaceutical industry and for-profit research companies were more likely to ‘vote’ in ways that reflected their own interests. We imagine that the results would probably have looked quite different in a London neighbourhood with a different social composition!

Still, in the end, the results of our activity show that members of the public care about how their data is used and are thinking about these issues in ways that reveal an awareness of the complexity involved. It’s clear that people’s concerns aren’t just about maximising data privacy in all instances – it’s about what data is shared with whom and when, and, perhaps most importantly, their trust that organisations will do as they say.

The results of this activity are helping to inform our work in PERC in understanding more about how members of the public feel about their personal data and its uses for research and healthcare purposes and we thank all those who participated.