By Kirsten Bell, Senior Research Fellow in Anthropology, Imperial Patient Experience Research Centre

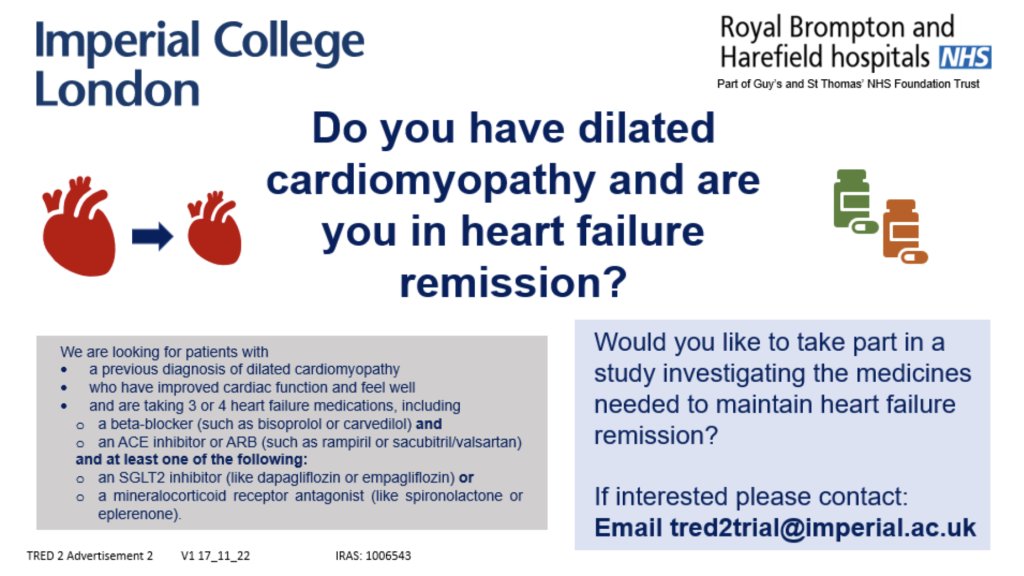

Imagine you have a heart condition—dilated cardiomyopathy (i.e., an enlarged heart)—that can be kept in remission with various medications. The only catch is that you’ll have to be on those medications for the rest of your life. Or do you? The ‘Therapy withdrawal in REcovered Dilated cardiomyopathy – Heart Failure’ (TRED-HF2) trial aims to explore whether it’s possible to reduce the number of medications patients with dilated cardiomyopathy take, while continuing to maintain remission.

A core impetus for the study, like the TRED-HF study before it, is the concerns patients often express about their medications, and the impact of their pill regimen on their quality of life. While the TRED-HF study found that heart failure remission rather than complete recovery is typical in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy who respond to therapy, and full withdrawal of medications is not advisable, the TRED-HF2 study is looking at whether medications can be fine-tuned.

Picture 1: TRED2 poster

Picture 1: TRED2 poster

Researchers in the Patient Experience Research Centre have been working with the TRED-HF team at Brompton Hospital to learn more about the experiences of patients in TRED-HF studies and how they feel about their heart medications. For participants in the TRED-HF study, we found that the volume of medications and side effects were a concern for many patients, along with apprehensions about being on medications for the rest of their life.

So far, we have found that patients in the TRED-HF2 study are more focused on the future effects of their medications than their current quality of life. However, two very different orientations are evident in their responses. For one set of patients and their families, medications act as a shield against future health consequences; for the other, they view themselves as paying a price for every pill they take.

Interested in further exploring the topic, we figured that the annual Cardiomyopathy UK conference was the ideal venue to delve into our findings and contextualise them in relation to the views of other people living with cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy UK is a national charity for people affected by cardiomyopathy, and their conference is a sell-out event. This year’s conference, held on November 16th in central London, was attended by 350 people, including patients with cardiomyopathy and their families.

Picture 2: Kirsten Bell and Kathryn Jones at the Cardiomyopathy UK conference – the activity is in the foreground

Using glass jars and tokens, we asked conference attendees to evaluate which statement best described how they feel about their heart medications: 1) ‘They shield me from future damage’ and 2) ‘You pay a price for every pill you take’. This activity led to a lot of interesting conversations. While not everyone we spoke to had dilated cardiomyopathy, they all had strong views on their medication.

Of the twenty 26 people we spoke with, they almost universally talked about how conflicted they were by the choice we presented, with virtually everyone telling us how difficult it was to choose between the two options. Still, in the end, the results were heavily weighted towards the idea that heart medications shielded patients from future damage: 18 people put a token in this jar, compared to 8 in the other.

Most people, it seemed, did feel that their heart medications shielded them from future damage—after all, this was why they had been prescribed the medication in the first

place! ‘You’re an idiot if you don’t take them’, one man bluntly told us. ‘I’d be lost without them’, said another. However, many had niggling concerns about the long-term consequences of such medications, and their potential impacts on other organs—like their kidneys.

Younger attendees, including a woman diagnosed with cardiomyopathy at 16, talked about how difficult it was to have to take pills for the rest of your life. She dropped her token into the ‘you pay a price for every pill you take’ jar while her father, who clearly thought the pills were necessary for his daughter’s health, dropped his token into the ‘they shield me from future damage’ jar.

Indeed, there may well be differences between patients and their families in terms of how they view the medication. Earlier, a woman who takes 48 pills a day said that the ‘shield’ jar was very much a carer’s perspective. She talked about the knock-on effects of medications—of having to take pills to deal with the side effects of other pills in an endless chain. For her, the choice was clear: ‘I really want to dump in 48 tokens’, she joked, as she placed her lone token into the ‘you pay a price for every pill you take’ jar.

In the end, the conversations we had with attendees at the Cardiomyopathy UK conferences have dramatically enriched our understanding of our research data and will inform our interviews for the TREDII study moving forward. Sometimes, we learned, medications really are a hard pill to swallow.

Acknowledgements: The TRED-HF2 study is being funded by Cardiomyopathy UK and the British Heart Foundation, which are also supporting our work, in addition to the Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, which funds Bell and Jones’ positions.