This blog was co-authored by Helix Centre designers Sophie Horrocks and Tori Simpson.

What if every act of care also cared for the planet?

From care pathways to medical products, healthcare can (and must) be designed to minimise waste, reduce emissions, and protect planetary health. This is not a distant vision, but an urgent necessity. As the world’s leading designers gather for the World Design Congress themed Design for Planet, here at the Helix Centre, we are exploring what it will take to make this ambition a reality, and the role human-centred design in healthcare can play in achieving it.

The connection between climate change and human health is increasingly clear. More frequent and severe heatwaves, floods, droughts, and storms directly harm health through injuries, heat stress, and other acute impacts. These events also indirectly affect communities by altering the spread of infectious diseases, driving food and water insecurity, damaging infrastructure, and deepening existing inequities. Together, they contribute to excess deaths and worsening physical and mental health outcomes (Haines et al., 2006; The Lancet, 2024).

Healthcare is also part of the problem. Globally, health systems produce around 5% of national CO₂ emissions in OECD countries (Pichler et al., 2019). In the UK, the sector accounts for 4–5% of total emissions, with the NHS in England responsible for about 40% of the public sector’s footprint (British Medical Association, 2024). At the same time, the climate crisis threatens the resilience of healthcare itself, with extreme weather disrupting services and rising health burdens straining already stretched systems.

These twin pressures highlight the urgent need for sustainable healthcare. By this, we mean the provision of health services in a way that meets the needs of today’s populations without damaging the health (or the ability to meet the healthcare needs) of people separated from us by time, geography, or socioeconomic status.

The challenge is significant, but it also highlights healthcare’s huge potential to drive change. Designing sustainable healthcare involves navigating trade-offs, such as balancing sterility requirements with reducing the footprint of medical equipment, while also seizing “win-wins” that benefit health, the environment, and even social and economic wellbeing.

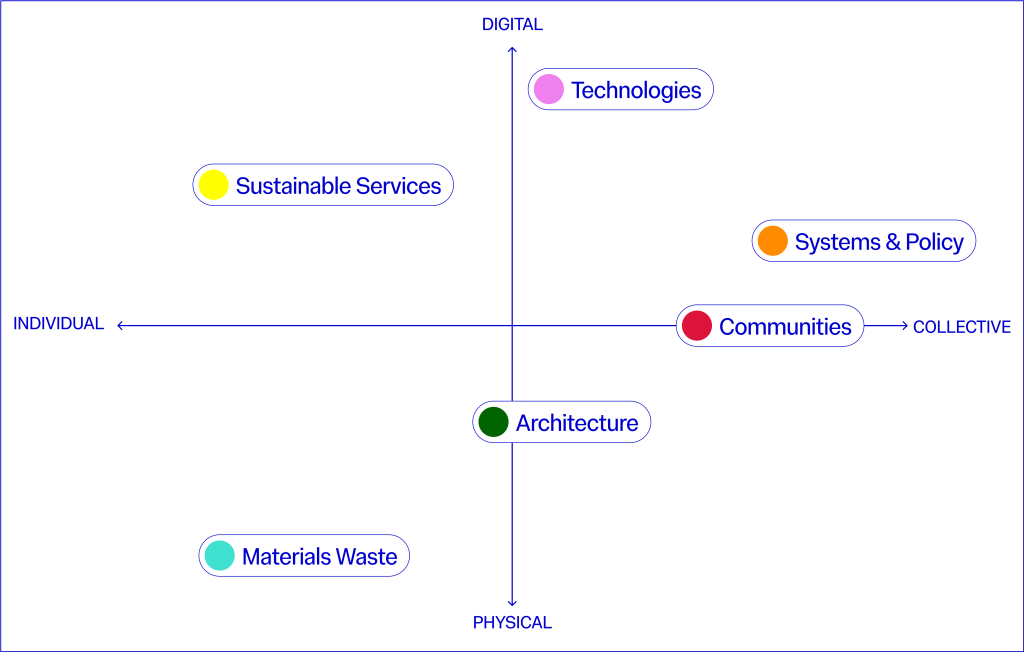

At the Helix Centre (and Imperial College London’s Institute of Global Health Innovation more broadly) we’re exploring this challenge through six “wicked problems” at the crossroads of healthcare and sustainability. We have mapped these onto a matrix with the following axes, and for each, we share how we define the issue, present a case study of inspiring work in the field, and highlight sessions we plan to attend at the World Design Congress to deepen our understanding.

Through this article, we aim to open a conversation on how designers and other practitioners working in healthcare delivery (ourselves included) can integrate sustainability challenges into the heart of their work. If these themes resonate with you, we’d love to hear your ideas and examples and explore together how we can create healthcare systems that protect both people and the planet – get in touch with us at climate@helixcentre.com.

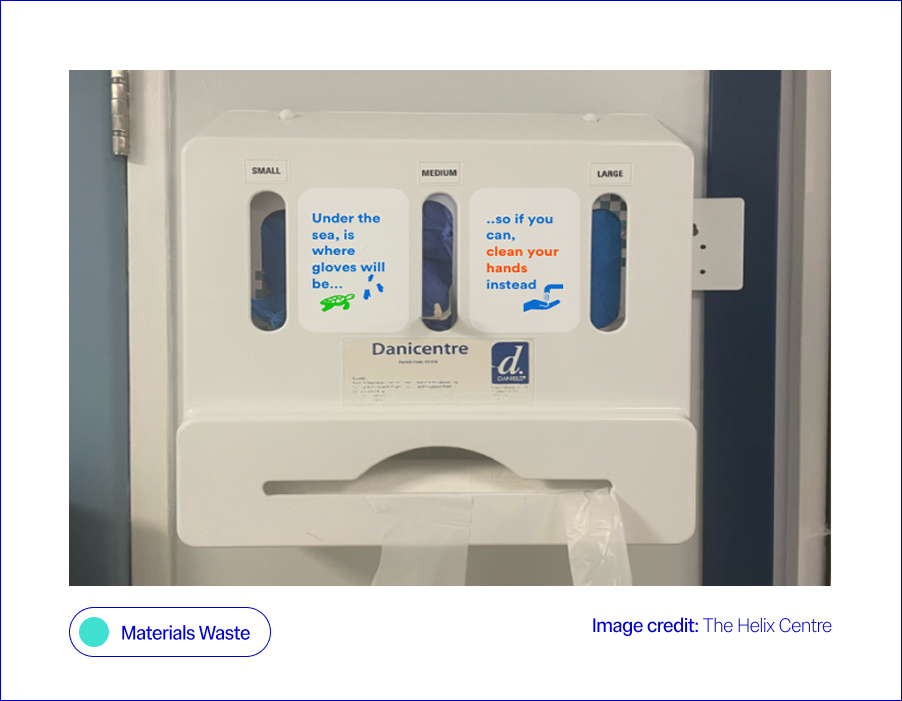

Materials Waste: Cutting the waste without cutting safety

What is the issue?

Every year, NHS England providers produce 156,000 tonnes of clinical waste. Tackling this could unlock major wins for both the environment and patient care. However, the answer isn’t simply reusing equipment. In healthcare, there is a complex trade-off between maintaining sterility requirements and limiting the environmental impact of medical equipment, particularly given that many essential items such as syringes and personal protective equipment (PPE) are single-use (Nicolet et al., 2022). Sterilising these single-use items for reuse can often be as carbon-intensive as replacing them after each use.

What is being done?

At Helix, we worked with a large NHS provider to test a behavioural “nudge” (a small design change that makes the sustainable choice easier without restricting options), aimed at improving hand hygiene practices and reducing the over-reliance on gloves. On hospital wards, glove use had become the default during the pandemic, often replacing standard hand hygiene practices like washing hands or using alcohol gel. To help staff return to safer, less wasteful habits, we co-designed a sticker for glove dispenser boxes, reminding staff when gloves were really needed. This small prompt (our “green nudge”) led to an 11% increase in hand hygiene compliance, meaning staff cleaned their hands more often at the right times, usually by washing with soap and water or using alcohol gel, in line with official guidelines (Blair et al., 2024). Outside of Imperial, the DesignHOPES team has worked with NHS staff to co-design a reusable theatre cap, designed to replace the current single-use ones. This intervention not only reduces waste but has also allowed for the personalisation of clinicians’ theatre caps, creating further wins for patient safety and staff identification. The Design for Life programme outlines an agenda and six fundamental challenges for our healthcare system in developing and embedding a circular system for medtech products.

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

Waste not, want not: from waste to wonder – a conversation between Sophie Thomas, Paula Chin, Adam Fairweather, Jo Barnard and Yaseed Chaumoo

Sustainable Services: Designing care pathways that care for people and the planet

What is the issue?

Care pathways are major contributors to the healthcare system’s carbon footprint. Fewer hospital visits, simpler procedures, and reduced prescribing could deliver large savings (NHS England, 2021). In summary, implementing quality improvement across care pathways with sustainability in mind can be a win-win in terms of environmental impact and patient outcomes (Health Foundation, 2025). Many trusts within the NHS are already assessing services against the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare’s all-encompassing definition of sustainability, which considers environmental, social and financial impacts as the foundational pillars in achieving sustainable services (NHS England, 2025). Alongside care pathways, food and transport services are listed as focus areas for the NHS’s green transition, cited as services that, if delivered more sustainably, could have a high impact on the NHS’s carbon footprint, with the two mentioned services comprising 20% of the health service’s total emissions (World Health Organisation, 2025).

What is being done?

Within Imperial, Matthew Harris explores opportunities for bidirectional learning between the NHS and low-income countries, including the implementation of various “frugal innovations” that use fewer resources to deliver healthcare, without compromising patient safety or clinical outcomes (Brown et al., 2023). Further afield, the GIRFT programme at Exeter University is developing a toolkit to map current carbon emissions and predict their impact on sustainability, financial aspects or care, patient outcomes, and equity of access. Within the NHS, the world’s first zero-emissions ambulance is being trialled in the West Midlands, setting an example for how other trusts can roll out more sustainable transport fleets, with the potential for dramatic carbon savings, given the NHS fleet is the second largest in the country (NHS England, 2023).

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

From Lab to Launch: How design accelerates Global Impact – an unconference with Paul Rodgers, Pete Broadbent, Suraj Vadgama, and Edward Hobson

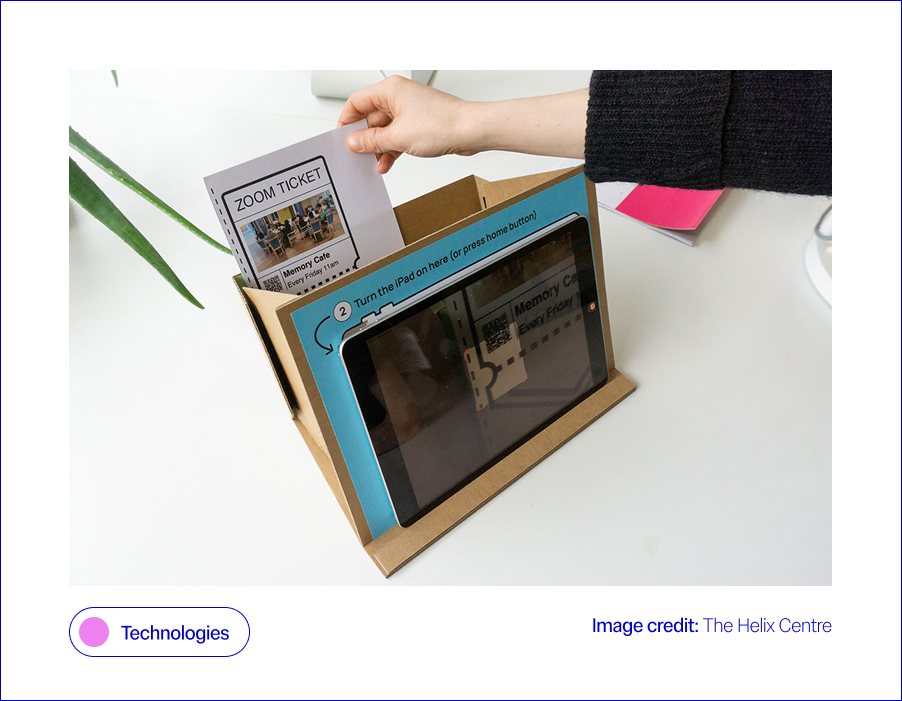

Technologies: Can digital health go green?

What is the issue?

Technology, such as digital tools and remote monitoring to support care, is central to the NHS’s plan to cut emissions. Reduced transport costs, greater efficiency, and a focus on digital preventative care are all given as examples of how better use of technology could fast-track the NHS’s green transition (HSJ Information Ltd., 2025). However, with the intention to use AI systems to support many of these technologies discussed in the NHS’s recently released 10-year plan, it is important to consider the environmental impact of these technologies when implementing them (NHS England, 2025). It is estimated that globally, the data centres that power the technologies in question accounted for around 1.5% of global electricity consumption in 2024, with this consumption projected to grow by 15% per year (International Energy Agency, 2024). Similarly, a single data centre on average uses 300,000 gallons of water a day for cooling, enough electricity to power 100,000 homes (Ziegler, 2024). Finally, the move towards a more technologically enabled NHS also comes with a risk of digital exclusion for vulnerable parts of the population, which must be carefully considered within the transition (Health Innovation Network, 2023).

What is being done?

Previously, Helix collaborated with the London Office of Technology and Innovation (LOTI) to create a prototype system to support people with little experience of technology to participate in online meetings, mitigating the risk of digital exclusion as the healthcare system transitioned more to online engagement, following COVID-19, a decision that had a knock-on positive effect on carbon emissions (Rothwell et al., 2023). Within IGHI, Aws Almukhtar, supervised by Gaby Judah and Daniel Leff, is embarking on a project that will demonstrate surgical simulation as a novel research tool for testing and refining behavioural interventions designed to decrease carbon emissions from operating theatres. By testing interventions in simulated operating theatres, researchers can identify and refine the most impactful new approaches that improve sustainability and cut waste while maintaining quality before they ever reach a patient. Importantly, surgical simulation makes it possible to explore interventions, such as eco-labelling surgical instruments, that could not be tested feasibly in live operating theatres without prior supporting data.

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

Communities, AI, and Collective Impact – a panel discussion between Sevra Davis, Michael Bennett, Suma Balaram Schippers, Anne Asensio, Bharat Kapoor, Dr Ramit Debnath, Michele Morris, Jayden Ali, Mattie Yeta, and Dr Geke van Dijk

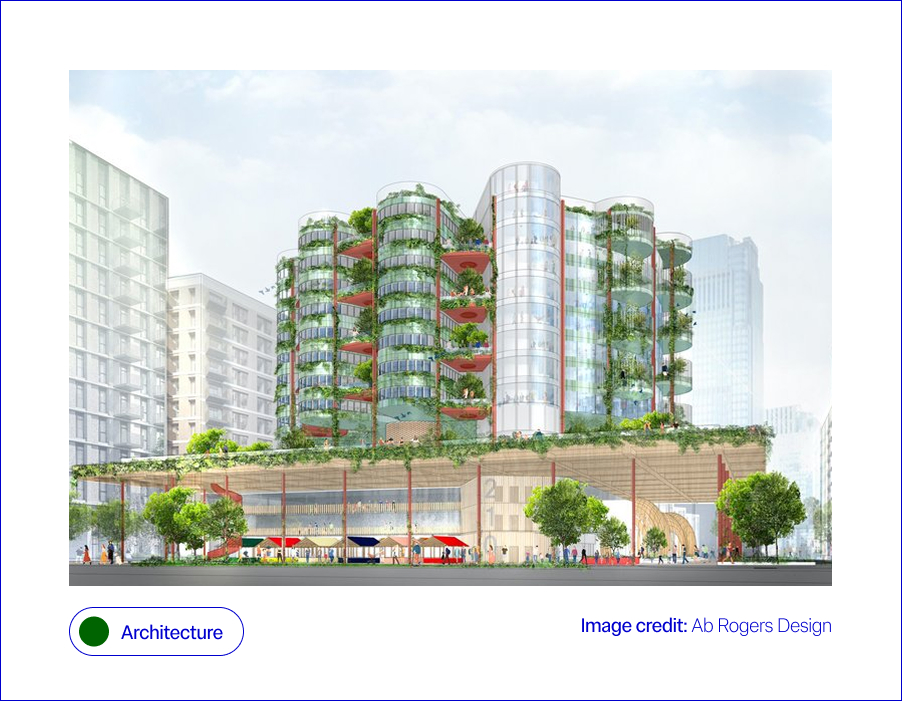

Architecture: Hospitals built for a sustainable future

What is the issue?

Hospitals are among the most carbon- and energy-intensive buildings, with 24/7 operations, complex equipment, and high heating and cooling demands. A 2024 systematic review highlights that hospitals contribute disproportionately to health sector emissions, with key drivers including energy use in buildings, embodied carbon in construction (the emissions tied to materials and construction), and waste streams (Public Health, 2024). Smarter building design and retrofits offer a clear path to reducing this impact. Alongside materials, “invisible” systems like ventilation or plumbing also affect sustainability performance and patient wellbeing. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, demanding that

hospital architecture becomes not only resilient to extreme weather, for example, floods and heatwaves, but also adaptive to future innovations. This means buildings must embrace digitally enabled architecture, where the physical fabric supports integration of new health technologies, automation, and data-driven energy systems (Design Council, 2021). In the context of architecture, sustainability is multi-layered, spanning bricks, wires, and human experience.

What is being done?

Responses span both future visions and practical action. Ab Rogers Design’s Living Systems reimagines hospitals as therapeutic spaces that integrate light, nature, and flexible layouts (RIBA, 2021). At a system level, the NHS Net Zero Building Standard (2023) is shifting net zero from exception to expectation. A powerful real-world example comes from Milton Keynes University Hospital, which re-roofed estate buildings and installed 2,586 solar panels. In 2021, these generated 853 MWh of electricity (around 8% of the hospital’s demand), cutting emissions, saving more than £225,000 annually, and improving patient comfort. The Trust plans to expand to 3,400+ panels, covering 15% of its needs (NHS England, 2021). Improving building resilience is also key: Loma Linda University’s hospital in California was designed to withstand seismic shocks, while UK trusts are retrofitting with double glazing and smart systems to reduce energy demand (Arup, 2023; BBC, 2023). Architectural consultancies like Buro Happold emphasise the need for adaptable hospitals that can withstand climate uncertainty while supporting patient wellbeing. Together, these examples show sustainability in healthcare estates is no longer aspirational; it is becoming standard practice for safer, greener patient care.

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

Design for Planet In Action: Fabrication, Futures, and Frontlines. Featuring: Samson Sahmland-Bowling, Peter Gitau, Alba Suárez Zapico, Charles Cambianica, Bethany Koby, Shajay Bhooshan

Building for the Future with Zoe Balmforth, Cameron Frayling, Hélène Chartier, Michael Pawlyn, Joanna Rowelle, Vanessa Miler-Fels

Communities: From hospitals to healthy communities

What is the issue?

NHS England’s Greener NHS strategy identifies “models of care” as a priority, recognising that moving services from hospitals into communities can significantly reduce emissions while improving quality of and access to care (NHS Long Term Plan, 2019). This has been further emphasised by the recently released NHS ten-year plan, which sets out a vision for a “Neighbourhood Health Service”, which shifts care into local communities, to “reintegrate healthcare into the social fabric of places” (Department of Health and Social Care et al., 2025). Hospitals are resource-intensive, whereas community-based services allow greener, more localised alternatives through hub-and-spoke systems and preventative care.

This shift is also vital for addressing the intertwined challenges of mental health and resilience in the face of climate change. Community-rooted care can provide both clinical and psychosocial support, enabling individuals and communities to adapt to climate-related stresses while easing pressure on hospitals. Community-based approaches, from preventative interventions to green social prescribing, demonstrate how models of care can reduce emissions while strengthening people’s physical and mental wellbeing (NHS England, 2021). Finally, any discussion of the built environment would be incomplete without noting the positive effects that access to nature and green space can have on health, mental wellbeing, and social connection, a powerful win-win where greener care spaces enhance both patient outcomes and climate resilience (Loveard, 2025). Ultimately, the challenge is not only to cut carbon but to reimagine care systems that also foster resilience, equity, and sustainability.

What is being done?

Innovative responses are emerging across different contexts. Within Imperial’s Institute of Global Health Innovation, the Climate Cares Centre is working with young people in the Philippines, Australia and the Caribbean to understand psychological responses to the climate crisis and co-design supportive interventions (Rising Faster than the Sea Levels). Climate Cares is also working to align climate change education and mental health support in schools and universities to support resilience building (the Compass Project). Climate Cares also works to connect and amplify existing initiatives around the world, such as ECO-MAMA, in Rwanda, which empowers women to safeguard mental health during climate stressors through an AI chatbot, and The Resilience Project in the UK, Europe and East Africa, which strengthens wellbeing through emotional regulation skills and social connection.

These programmes illustrate how initiatives can build resilience while broadening the ways in which care and wellbeing support are delivered. Building on this, research led by Matthew Harris has championed the role of community health worker models, drawing on international experience to strengthen local health delivery (Imperial College London, 2021). At the system level, the NHS has also expanded green social prescribing pilots, embedding nature-based activities into care pathways to support wellbeing and healthcare sustainability (NHS England, 2021). Together, these efforts sit within the broader framework of the NHS 10-Year Plan, which sets out a national roadmap for embedding greener, more personalised, and more resilient systems of care (NHS Long Term Plan, 2019).

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

Communities, AI, and Collective Impact featuring: Dr Geke van Dijk, Jayden Ali, Michael Bennett, Michèle Morris, Sevra Davis, Suma Balaram Schippers, Anne Asensio, Bharat Kapoor, Mattie Yeta, Dr Ramit Debnath

Systems and policy: From policy to practice: embedding green healthcare

What is the issue?

Sustainable healthcare requires action at every level, from national policy frameworks to the day-to-day choices of staff and patients. The climate crisis can feel like an added pressure for already stretched health systems, but there are clear “win–wins” to be found; just as insulating homes can cut energy bills and improve health whilst reducing emissions, similar opportunities exist in healthcare when policy and practice align. Top-down change is essential for embedding sustainability into governance, investment, and regulation, setting the conditions for lasting change. Simultaneously, bottom-up engagement is equally vital: sustainability can feel overwhelming or abstract for those working on the front line, so it matters how staff and communities understand and shape what is achievable in practice. Embedding resilience, therefore, requires not only policy and infrastructure but also a workforce that is equipped, supported, and motivated to act. Without this support, the resilience of the health workforce itself is at risk, with overwhelm and burnout threatening the very capacity needed to deliver sustainable care (Lawrence et al., 2024).

Behaviour change is a critical link between these levels; while many people recycle diligently at home, they may not apply the same habits at work or in public spaces such as hospitals. This underscores the importance of cultural as well as technical shifts, and the need to prioritise collective action, rather than an overemphasis on individual responsibility (Lawrance et al., 2022; van den Berg, 2015). Ultimately, progress depends on aligning ambitious policy with everyday behaviour change, supported by training and upskilling that empowers people at every level of the system (Michie et al., Behaviour Change Wheel).

What is being done?

Change is being driven from both the top down and the bottom up. At the policy level, the Health and Care Act 2022 made the NHS the first health system globally to embed statutory net zero and environmental duties into law, requiring NHS England, trusts, and integrated care boards to factor sustainability into their decisions (NHS England, 2022). This commitment is reinforced by the wider NHS Net Zero plan and efficiency-focused programmes such as Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT), which cut waste and emissions while improving care (GIRFT, 2024). At the organisational level, Green Plans provide a framework for trusts to set out three-year roadmaps towards more sustainable estates and services (NHS England, 2021).

Alongside this, bottom-up change is supported through training and workforce development: for example, the Climate Cares Centre at IGHI co-developed an Apolitical course, equipping policymakers with the knowledge and skills to address climate change and mental health simultaneously. Behavioural interventions are also crucial, helping staff to embed sustainable habits in clinical and operational settings; bridging the gap between what people already practise at home, like recycling, and what feels achievable in a healthcare context. To accelerate progress, policy must scale up these “win–wins” that make sustainable choices easier, so patients, staff, and organisations alike can help drive a greener future, through both everyday decisions and long-term strategies.

Where we’ll be at the World Design Congress to learn more:

Designing the Economy We Need: Missions, Doughnuts, and Radical Collaboration with Mariana Mazzucato, Kate Raworth, Danny Sriskandarajah

Closing statement

The climate emergency is reshaping how we think about the way we provide healthcare. But this is also a design opportunity: to build systems that are not only safer and more effective, but also sustainable, resilient, and equitable. At Helix, we see our role as creating the conditions for this transformation: using human-centred design to tackle the toughest challenges at the crossroads of health and sustainability. The World Design Congress is a chance to learn, to share, and to build alliances with others who are equally committed to designing for the planet. Our contribution is to bring healthcare into this conversation, surfacing challenges, testing solutions, and creating space for collaboration. Beyond the Congress, we hope to serve as a bridge between designers and healthcare systems, so that bold ideas can become practical realities. By recognising these trade-offs and scaling the win–wins, we can design healthcare that is safer, greener, and more equitable, for both people and the planet.

We invite fellow designers, practitioners, and partners to join us in shaping that future together: climate@helixcentre.com.

With enormous thanks to Aws Almukhtar, Daniella Watson, Jessica Newberry Le Vay, Leila Shepherd, Matt Harrison, and Natalia Kurek, who have helped us shape our thinking in this space.

Reference List

Arup (2023) Loma Linda University Health: Dennis and Carol Troesh Medical Campus. Available at: https://www.arup.com/projects/loma-linda-university-health-dennis-and-carol-troesh-medical-campus.

BBC News (2023) Milton Keynes Hospital installs solar panels to cut emissions. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cz4dyj70dyvo.

Blair, C-J., McCrudden, C., Brazier, A., Huf, S., Gregory, A., O’Driscoll, F., Galletly, T., Leon-Villapalos, C., Brown, H., Clay, K., Maxwell, S., Anakwe, R. and Grailey, K. (2024) ‘A helping hand: Applying behavioural science and co-design methodology to improve hand hygiene compliance in the hospital setting’, PLOS ONE, 19(12), e0310768. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0310768.

British Medical Association (2024) More support needed to help the NHS reach net zero. British Medical Association. Updated 28 June 2024. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/what-we-do/population-health/protecting-people-from-threats-to-health/more-support-needed-to-help-the-nhs-reach-net-zero

Brown, C., Bhatti, Y. and Harris, M. (2023) ‘Environmental sustainability in healthcare systems: role of frugal innovation’, BMJ, 383(8401), Article e076381. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076381.

Department of Health and Social Care, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, The Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer KCB KC MP and The Rt Hon Wes Streeting MP (2025) Fit for the Future: 10 Year Health Plan for England. First published 3 July; updated 30 July 2025. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/

Design Council (2021) The Future of Health and Healthcare Design. London: Design Council. Available at: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/fileadmin/uploads/dc/Documents/future-health-full_1.pdf.

GIRFT (2024) Getting It Right First Time: Net Zero and Sustainability. Available at: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/cross_cutting_theme/net-zero-sustainability

Haines, A., Kovats, R.S., Campbell-Lendrum, D. and Corvalán, C. (2006) ‘Climate change and human health: Impacts, vulnerability and public health’, Public Health, 120(7), pp. 585–596. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.002.

Health Foundation (2025) Why environmental sustainability must be at the heart of reform if the 10-year health plan is to help the NHS reap the benefits for patients, the health system and … [Blog]. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/features-and-opinion/blogs/why-environmental-sustainability-must-be-part-of-the-10-year-health-plan

Health Innovation Network (2023) Bridging the Digital Divide in NHS Transformation: Ensuring Inclusivity and Equity [Blog]. Published 18 December 2023. Available at: https://healthinnovationnetwork.com/insight/bridging-the-digital-divide-in-nhs-transformation-ensuring-inclusivity-and-equity/

HSJ Information Ltd. (2025) Moving Towards Net Zero through Digital, HSJ Digital Awards [webpage]. Available at: https://digitalawards.hsj.co.uk/award-category/moving-towards-net-zero-through-digital

Imperial College London (2021) From Brazil to Westminster: Learning from a community health worker model. Available at: https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/entities/publication/256305ad-73a4-4e7e-afa2-3c6af23369d2.

International Energy Agency (2025) Energy demand from AI. Paris: International Energy Agency. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/energy-demand-from-ai

Lawrence, W., et al. (2024) ‘Sustainable health systems and workforce resilience’, BMJ, 387, e081284. doi:10.1136/bmj-2024-081284.

Lawrance, E.L., Thompson, R., Newberry Le Vay, J., Page, L. and Jennings, N. (2022) ‘The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence, and Its Implications’, International Review of Psychiatry, 34(5), pp. 443–498. doi:10.1080/09540261.2022.2128725.

Loveard, D. (2025) ‘Nature for Health: Making Green Space Work in Healthcare’, NHS Forest Blog, 23 June. Available at: https://nhsforest.org/blog/nature-for-health-resource-hub/

Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M. and West, R. (2011) ‘The Behaviour Change Wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions’, Implementation Science, 6(42). doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

NHS England (2019) The NHS Long Term Plan. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/.

NHS England (2021) Green Plan Guidance for Trusts. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/green-plan-guidance/.

NHS England (2023) Net Zero travel and transport strategy, in Net zero travel and transport strategy [Greener NHS]. Published 31 October 2023. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/net-zero-travel-and-transport-strategy/#2-approach-and-methods

NHS England (2024) Greener NHS Strategy. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/a-net-zero-nhs/areas-of-focus/.

NHS England (2025) Building on what we already do, in Understanding environmental sustainability [Greener AHP Hub]. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ahp/greener-ahp-hub/understanding-environmental-sustainability/building-on-what-we-already-do/

NHS England (2025) Fit for the Future: 10 Year Health Plan for England [webpage]. Published 3 July 2025. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/

Nicolet, J., Mueller, Y., Paruta, P., Boucher, J. and Senn, N. (2022) ‘What is the carbon footprint of primary care practices? A retrospective life-cycle analysis in Switzerland’, Environmental Health, 21:3. doi:10.1186/s12940-021-00814-y.

Pichler, P.-P., Jaccard, I., Weisz, U. and Weisz, H. (2019) ‘International comparison of health care carbon footprints’, Environmental Research Letters, 14(6). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab19e1.

Public Health (2024) ‘Hospitals’ contribution to health sector emissions: a systematic review’, Public Health, 232, pp. 74–86. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2024.01.002.

RIBA (2021) Opportunities for health design research: Ab Rogers Living Systems. Available at: https://www.ribaj.com/intelligence/opportunities-health-design-research-wolfson-living-systems-ab-rogers

Romanello, M., Walawender, M., Hsu, S.-C., Moskeland, A., Palmeiro-Silva, Y., Scamman, D., Ali, Z., Ameli, N., Angelova, D., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Basart, S., Beagley, J., Beggs, P. J., Blanco-Villafuerte, L., Cai, W., Callaghan, M., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chambers, J. D., Chicmana-Zapata, V., … Costello, A. (2024) ‘The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: facing record-breaking threats from delayed action’, The Lancet, 404(10465), pp. 1847–1896. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01822-1.

Rothwell, E., Surtees, R., Allwood, D. and Gopfert, A. (2023) ‘Virtual appointments—embracing the opportunity to reduce carbon emissions mustn’t widen health inequalities’, BMJ, 381, Article p1169. doi:10.1136/bmj.p1169.

The Lancet (2024) ‘Editorial: Climate crisis and excess deaths’, The Lancet, 404(10419), p. 703. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01822-1.

van den Berg, M. (2015) ‘Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment’, Science of the Total Environment. Available at: [URL]

World Health Organisation (2025) How can health care facilities reduce their environmental footprint and contribute to more sustainable health systems?, Policy Brief 68. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Published 8 July 2025. Available at: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/how-can-health-care-facilities-reduce-their-environmental-footprint-and-contribute-to-more-sustainable-health-systems