In a letter published in the British Journal of General Practice, medical students Fahmida Mannan and Zain Chaudhry from the Imperial College London School of Medicine discuss how the NHS and medical schools can encourage students to consider general practice as a career option. They suggest the focus in medical schools should shift towards improving the quality of general practice placements and promoting the integration of primary care and specialist teaching, rather than consuming more time in an already overstretched curricula.

They also consider that prestige has never been the main incentive for pursuing a specialty. Their own experience is that many medical students are attracted to a career in general practice because of other factors, such as a good work–life balance, continuity of care and career flexibility. With many GPs now concerned about their workload, this inevitably influences students and junior doctors in their career choices.

Another key factor is the funding that a specialty receives. In recent years, the proportion of the NHS budget spent on primary care has decreased, GPs’ workload has increased and the income of GPs has fallen. To recruit more GPs, medical schools should improve the quality of students’ experiences in their primary care placements. However by itself, this will not be sufficient to improve recruitment and the onus falls upon the NHS to once again make general practice a rewarding career for doctors.

We are now seeing some signs of this. For example, the NHS England Five Year Forward Strategy emphasises the importance of primary care to the NHS and proposes new employment models for general practitioners. This includes the formation of GP Federations in which general practitioners will come together to work in larger groups; and the possibility that hospitals could also employ GPs and offer primary care services.

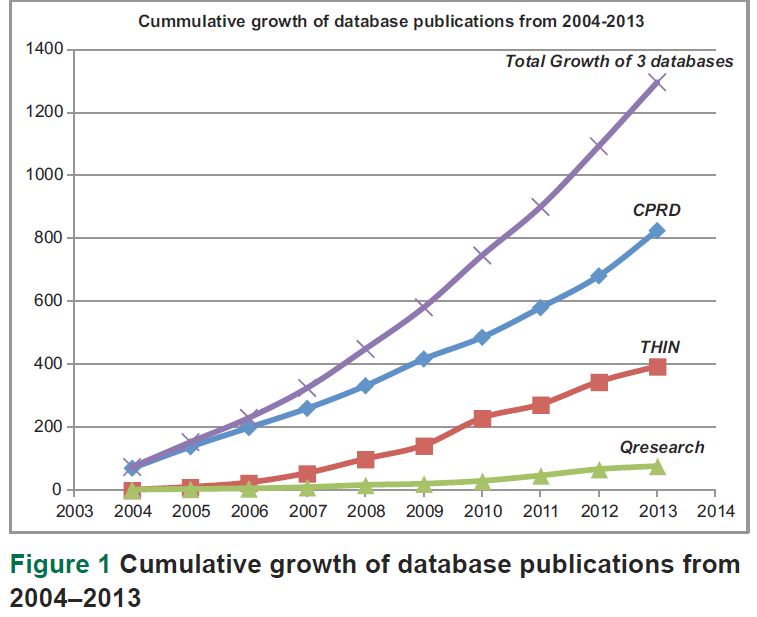

Data collected in electronic medical records for a patient in primary care can span from birth to death and can have enormous benefits in improving health care and public health, and for research. Several systems exist in the United Kingdom (UK) to facilitate the use of research data generated from consultations between primary care professionals and their patients.

Data collected in electronic medical records for a patient in primary care can span from birth to death and can have enormous benefits in improving health care and public health, and for research. Several systems exist in the United Kingdom (UK) to facilitate the use of research data generated from consultations between primary care professionals and their patients.