I published an article in the British Medical Journal in August 2017 on NHS England’s plan to reduce wasteful and ineffective drug prescriptions. In the article, I explain why national rules on prescribing are a better approach than the variable local policies being implemented by clinical commissioning groups (CCGs, the NHS organisations responsible for funding local health services).

The National Health Service (NHS) in England must produce around £22 billion of efficiency savings by 2020. A key component of the NHS budget in England is primary care prescribing costs, currently around £9.2 billion annually. Inevitably, the NHS has begun to look at the drugs prescribed by general practitioners to identify areas in which savings could be made; ideally without compromising patient care or worsening health inequalities. This process was initially led by CCGs, focusing on drugs that are either of limited clinical value or which patients can buy from retailers without a prescription (referred to in England as ‘over the counter’ preparations).[1]

However, this local-based approach is flawed.[2] Firstly, CCGs have no legal power to limit the prescribing of drugs by general practitioners. As CCG policies on restricting prescriptions are not backed by statutory guidance, this will inevitably lead to variation between general practitioners in the use of the drugs that CCGs are proposing to restrict, thereby leading to ‘postcode prescribing’. It also raises legal issues in that if there is a complaint about a refusal to issue a prescription, it will be the general practitioner who will have to defend any complaint made by the patient and not the CCG. Each CCG carrying its own evidence review, public and professional consultation, and developing its own implementation policy also results in duplication of effort and is a poor use of NHS resources.[3]

NHS England has now launched its own consultation process to identify areas where ‘wasteful or ineffective’ prescribing can be reduced.[4] However, although a national process is better than local processes, NHS England has not stopped CCGs from continuing to roll-out their own restrictions on prescribing, even though some of these will inevitably conflict with the guidance produced by NHS England when it completes its consultation process.

In its consultation document, NHS England proposes restrictions on prescribing for a range of drugs. Stopping prescribing in some areas – such as homeopathy and herbal remedies – will not be controversial but will also not save much money. Some other drugs that NHS England is proposing to restrict, such as liothyronine, have limited evidence for their benefits but some patients do find them useful, and there will be resistance from patients and from some clinicians about the proposed restrictions on their use.

The two most controversial areas will be around NHS prescriptions for gluten-free foods, for which there was a separate consultation;[5] and NHS prescriptions for drugs available over the counter. In the case of gluten-free foods, these are essential for people with coeliac disease and although gluten-free foods are now much more widely available from retailers than in the past, many patients with coeliac disease continue to receive NHS prescriptions and will resist strongly any restrictions on the availability of gluten-free foods through the NHS[6]. For drugs available over the counter, for example treatments for headlice or hay-fever, many patients will be able to pay for them out-of-pocket. Some poorer patients though will struggle with the costs of buying such drugs.

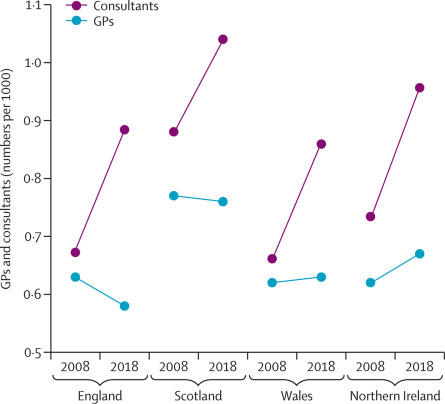

NHS England is to be congratulated for launching its public consultation and not just leaving decisions about eligibility for NHS treatment to individual CCGs.[7] However, it needs to ensure that its recommendations are accepted by CCGs and that the restrictions on prescribing that some CCGs are trying to impose fall into line with national recommendations. NHS England also needs to make the necessary changes to the National General Practice Contract and to the NHS Drugs Tariff to ensure that any prescribing restrictions it imposes have a firm legal basis. If this is not done, it places general practitioners in the invidious position of being at clinical and legal risk if they adopt NHS England’s prescribing guidance when this is finally published, at a time when they are already under considerable workload pressure.[8,9]

Restrictions on prescribing and the reduced availability of drug treatments on the NHS will have adverse consequences. For example, there is a risk of unintended effects such as codeine-based analgesics being used in place of simpler analgesics like paracetamol or Ibuprofen if the use of the latter is restricted. We also need to ensure that prescribing restrictions do not affect patients with very serious conditions. For example, if restrictions are imposed on NHS prescriptions of laxatives because these are available to buy from retailers, this will impact on patients with cancer, in whom constipation is a common and distressing symptom.

There will also be a risk that poorer patients, who are less able to pay for their own medication, will suffer disproportionately from these restrictions, thereby exacerbating health and social inequalities.[10] Ultimately, however, politicians and the public must understand that the financial savings the NHS in England needs to make are so large, they cannot be made without substantial cuts to the provision of publicly-funded health services; and without patients making a greater financial contribution to the costs of their health care.[11,12]

doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3679

References

1. North West London Collaboration of Clinical Commissioning Groups. Choosing wisely – changing the way we prescribe. https://www.healthiernorthwestlondon.nhs.uk/news/2017/06/12/choosing-wisely-changing-way-we-prescribe

2. Iacobucci G. Doctors call for national rules on OTC prescribing. BMJ 2017;356:j1442

3. Phizackerley D. National approach to OTC prescribing is needed. BMJ 2017;357:j1849.

4. NHS England. Items which should not be routinely prescribed in primary care: a consultation on guidance for CCGs. https://www.engage.england.nhs.uk/consultation/items-routinely-prescribed/

5. Department of Health. Availability of gluten-free foods on NHS prescription. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/availability-of-gluten-free-foods-on-nhs-prescription

6. Kurien M, Sleet S, Sanders DS, Cave J. Should gluten-free foods be available on prescription? BMJ 2017;356:i6810.

7. Iacobucci G. NHS to stop funding homeopathy and some drugs in targeted savings drive BMJ 2017;358:j3560.

8. British Medical Association. BMA responds to NHS England action plan on wasteful drug use. https://www.bma.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/2017/july/bma-responds-to-nhs-england-action-plan-on-wasteful-drug-use

9. Majeed A. Shortage of general practitioners in the NHS. BMJ 2017;358:j3191.

10. Gleed G. Commentary: We’re under financial strain without prescriptions for gluten-free food. BMJ 2017;356:j119.

11. Toynbee P. Feet first, our NHS is limping towards privatization. The Guardian, 16 August 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/16/feet-nhs-limping-towards-privatisation-podiatry-diabetic-amputations

12. Iacobucci G. GPs urge BMA to explore copayments for some services. BMJ 2017;357:j2503.

Read NHS England’s plan to reduce wasteful and ineffective drug prescriptions in full