What does a future with better lung health look like — and what will it take to get there? On World COPD Day, Professor Nick Hopkinson and Dr Keir Philip from the National Heart and Lung Institute explore new evidence that highlights the urgent need for action. COPD is not just a disease of the lungs; it’s a condition deeply rooted in poverty and inequality. From early-life disadvantage to harmful exposures like tobacco smoke, air pollution, and poor housing, deprivation shapes both who develops COPD and how they live with it.

It is well established that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is linked to poverty and inequality[1] . The exposures that cause people to develop the disease – tobacco smoke and air pollution as well as occupational dust, fumes, and chemicals are linked to deprivation. Early life disadvantage – poor nutrition, infections and lack of access to healthcare, also hampers normal lung development, increasing the risk of COPD.

On World COPD Day, we have published the results of research done in collaboration with the charity Asthma + Lung UK demonstrating that material deprivation doesn’t only cause COPD. It also influences what happens to people once they have the condition, and how this in turn increases the burden on individuals and the NHS[2].

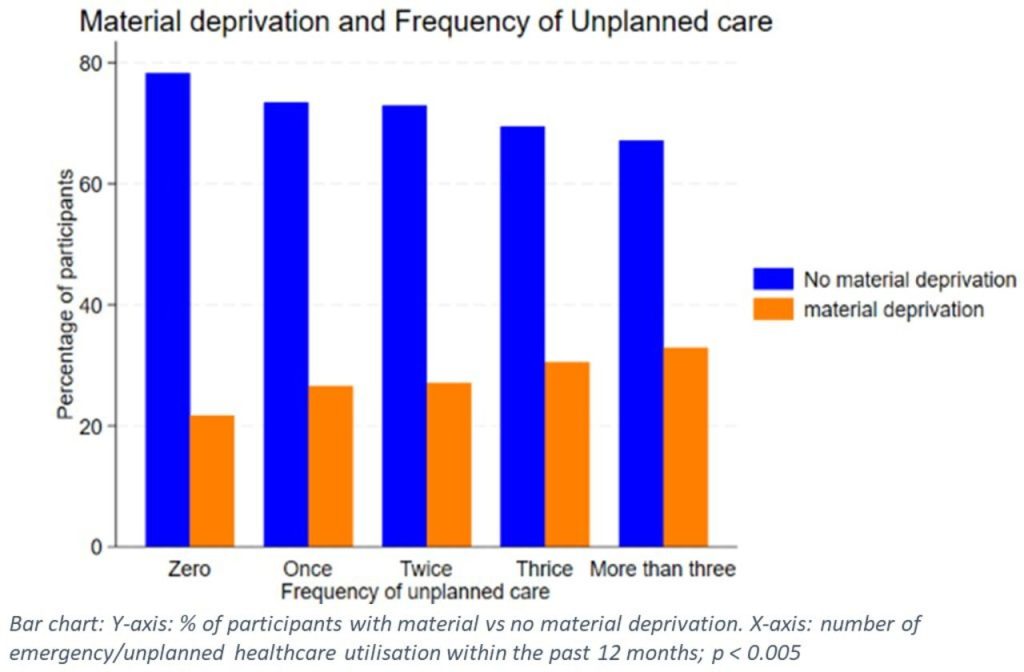

In a large national survey of 3,472 adults with COPD, we examined how material deprivation relates to emergency and unplanned healthcare utilisation (EUHU) such as attending A&E. Material deprivation refers to not being able to afford certain basic things in life like energy bills, adequate food, or keep your house warm. Many of these are basic requirements for living well with lung conditions and avoiding acute deteriorations. EUHU are costly for both the patient and the healthcare system, and accident and emergency departments are struggling to cope. In our study we found individuals experiencing material deprivation had a 27% higher odds of more frequent unplanned healthcare use, independent of age, gender and smoking status.

A particularly important finding was the strong association between inadequate home heating and cold or damp housing and increased EUHU. Over one in four participants reported being unable to keep their home adequately warm, and cold or damp living conditions were clearly linked to a higher likelihood of emergency care.

These results further extend findings that poor-quality housing—especially cold and damp environments—is closely linked to unplanned healthcare use in COPD[3]. Such living conditions are known to worsen respiratory symptoms, increase susceptibility to exacerbations, and limit the effectiveness of self-management.

The government was elected with a manifesto commitment to deliver a cross-government health mission. The introduction of Awaab’s Law requiring providers of social housing to address problems quickly is crucial step in the right direction, but it needs to be extended to private landlords as soon as possible, alongside broader redistributive policies to end poverty, in particular child poverty.

The findings of this research reinforce the need for comprehensive policy interventions to improve housing conditions and thus improve lung health, in order to reduce avoidable emergency care, alleviate pressure on the NHS, and improve the lives of the more than one million people living with COPD in the UK.

1 Williams PJ, Buttery SC, Laverty AA, et al. Lung Disease and Social Justice: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease as a Manifestation of Structural Violence. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2024; 209:938-946

2 Adesibikan A, Williams PJ, Cumella A, et al. Relationship of material deprivation with emergency or unplanned healthcare utilisation in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from an Asthma+Lung UK survey. BMJ Open Respir Res 2025; 12

3 Williams PJ, Cumella A, Philip KEJ, et al. Smoking and socioeconomic factors linked to acute exacerbations of COPD: analysis from an Asthma + Lung UK survey. BMJ Open Respiratory Research 2022; 9:e001290