Biomedical Engineer Shruti Turner reflects on the recent CRISH (Co-creating Innovative Solutions in Health) course and explains that engineers could learn a lot from PPI.

With a background in Aerospace Engineering, I didn’t really come from a culture of engaging people in my research. I moved across to Biomedical Engineering for my Masters and PhD, because I wanted to do something that was of direct benefit to people. Even though that was my reason for pursuing Biomedical Engineering, it was still a bit of a shock to the system that people were going to be involved in the research process.

What is often overlooked in biomedical engineering is that we are often developing solutions to benefit people’s lives. It is not just about solving statistics and maximising variables in an equation. How do we know where to start? What’s the most important thing to minimise? What compromises are acceptable to those who experience the problems?

It made sense to me that people, in this case the patients, would help me figure out my research priorities in terms of what technology would be useful. The newer concept to me was involving them throughout my research process. Logically it makes sense: I am fortunate enough to be a relatively healthy individual, but that means I lack a true understanding and experience of what it’s like to, for example, be an amputee. How can I, as an able-bodied individual, design a great piece of technology for an amputee without getting their feedback? Not only is their perspective important, but also people who spend long periods of time with them, such as their rehabilitation teams or their families.

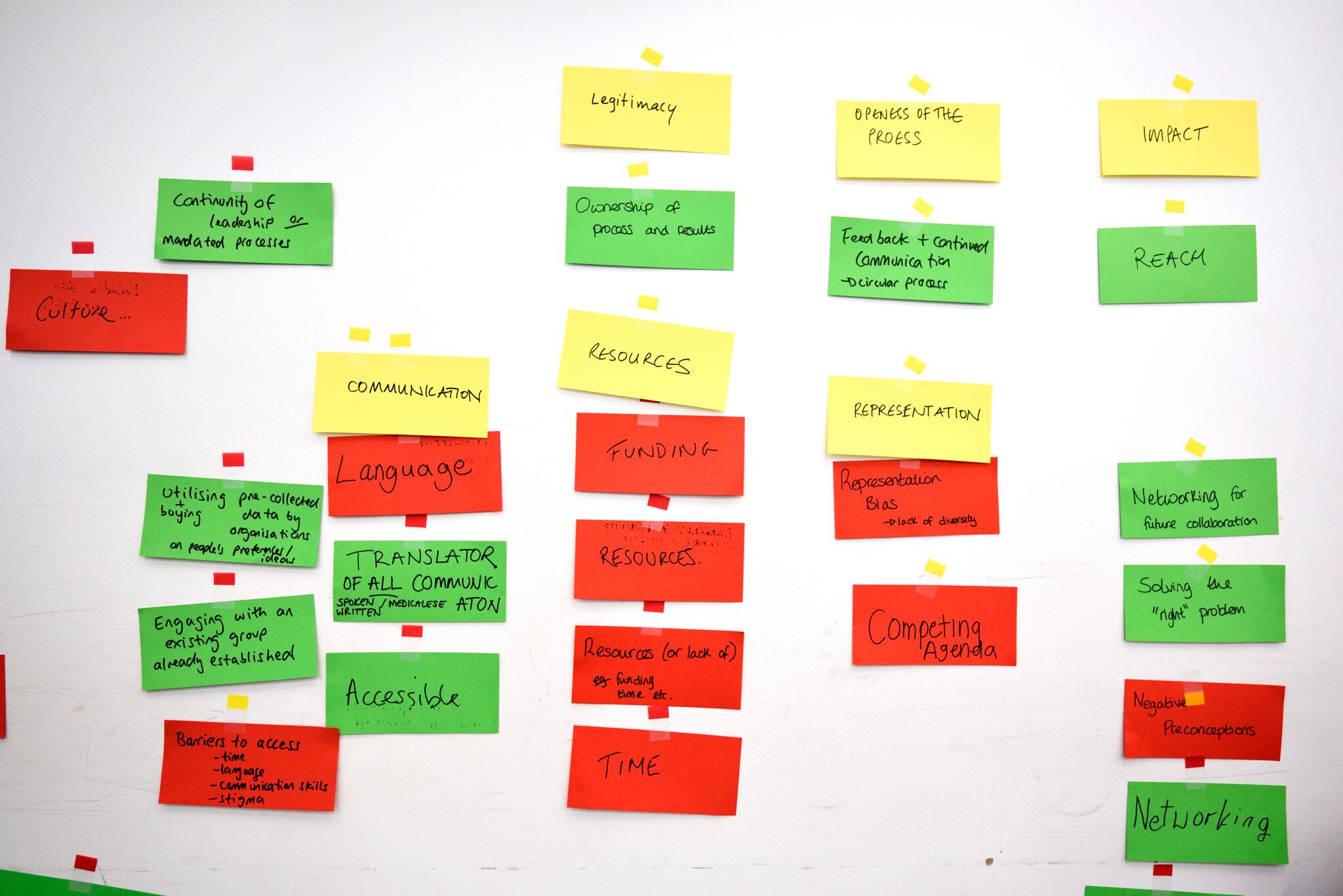

Attending the CRISH course really helped me work out how to involve different people in the research process. It’s one of those things that I knew I needed and wanted to do, but the how is often the most difficult. The course challenged us to think creatively about how to engage people. The course gave me the skills to map out my own project in a logical way to work out who to involve and how.

Engaging with “public experts” doesn’t stop us as engineers being experts in our own ways. I would be surprised if a lot of the patients I’m working with could do the programming and modelling that I’m doing (but if they are that’s a bonus for me as it’s extra insight!) Research happens in teams for a reason, because people have different expertise beyond just academic expertise. Bringing key beneficiaries of your design around the table can help you: you’re likely to have a better result which is more widely adopted.

As an engineer, particularly a Biomedical Engineer, I don’t believe it is my job to design something I think is great and impose it upon those I think should use it. It’s my job to help improve quality of life and to do that I must listen to experts who can help me make my design much more worthwhile.

There’s no point putting the time, money effort and resource into something that isn’t wanted, doesn’t work and won’t be used.

You can follow the progress of Shruti’s PhD on Twitter @ShrutiTurner and learn more about PPI on our Resource Hub.

2 comments for “What can an engineering PhD student learn from PPI?”

Comments are closed.