To kick off the Autumn series of our ‘Health Research Matters’ lunchtime seminar series, we brought together two speakers to share their experience of co-production with young people:

- Dr Christina Atchison, talked about ‘Adolescents 360‘, a project that used human-centred design to co-produce context-specific reproductive health programming initiatives with adolescents in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania; and

- Matt Walsham, from Partnership for Young London, who shared insight into working with young people on research across the voluntary sector

In case you weren’t able to attend, and as a reminder for those who did, here are some of the key take home messages from the two presentations, followed by the main discussion points and links to further reading.

PRESENTATION SUMMARIES

TALK 1: Dr Christina Atchison (Principal Clinical Academic Fellow, School of Public Health, Imperial College London) on ‘Adolescents 360’ and how to evaluate a human-centred design process.

What is Human-Centred Design?

Christina started her talk with a quick introduction to the meaning of human-centred design.

“A framework that comes up with solutions by involving the human perspective throughout the problem-solving process. The human involvement usually takes place through observing the problem within context, interviewing the community that would be affected by the outcome of the design process, and designing in collaboration with the people that one is serving. Together, this results in solutions that closely correspond with the needs of the target group.”

But she explained that it’s more of a mindset than a specific formalised process, where people and their needs are at the centre of your thinking.

About the ‘Adolescents 360’ (A360) project

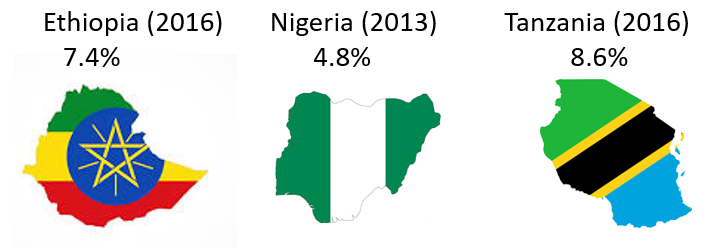

Launched in January 2016 by PSI with a core consortium of partners, A360 is a four-year project aimed to increase access to and uptake of voluntary, modern contraceptive use among adolescent women between the ages of 15 and 19 in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania.

“The project brings together leading experts in public health, social marketing, human-centred design, developmental science and cultural anthropology. Our hypothesis is that through a fusion of these disciplines, combined with meaningful engagement of young people in all phases of the project, we will catalyze a series of novel approaches to program design and delivery that can be replicated and scaled by partners and governments around the world.” – PSI. Find out more in this A360 brochure.

Why is adolescent reproduction health important?

Globally, approximately 16 million women aged between 15 and 19 years give birth each year and 95% of these births take place in low/middle-income countries. Adolescents have high rates of unintended pregnancy, which can lead to a range of adverse physical, social and economic outcomes including not reaching their potential for educational achievement, and not getting a paid job which usually leads into a vicious cycle of poverty. In 2015, maternal conditions were the leading cause of death in females aged between 15 and 19 years according to World Health Organization (WHO) data, causing 10 deaths per 100 000.

In all three countries of interest in the A360 project, use of modern contraception among women aged 15–19 years old was below 10%, highlighting a great need for innovative and tailored reproductive health programming in these settings. As a comparison, this figure is around 66% in the UK and US (Nsanya et al., 2019).

Ways of working

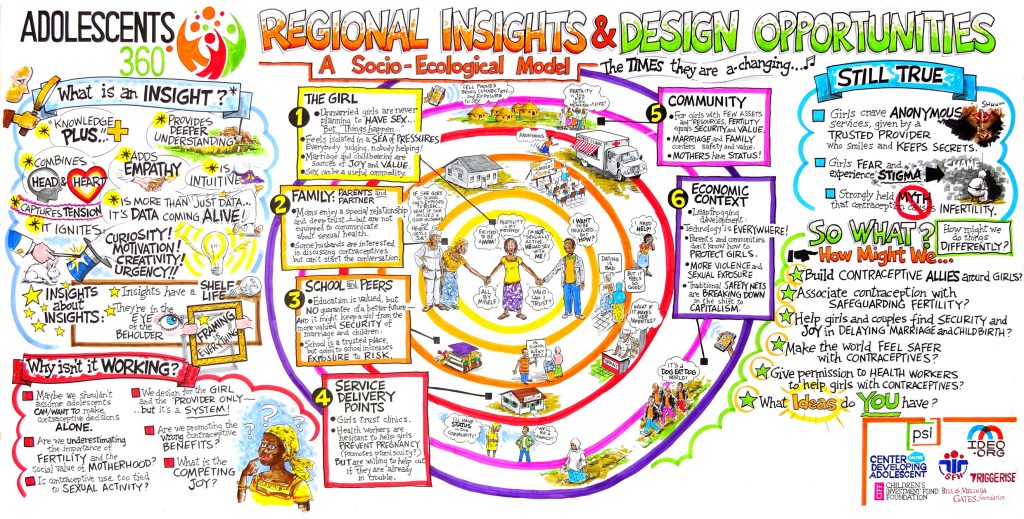

Christina took us through four key steps in the A360 project human-centred design process:

1. Inquiry (Inspiration)

The inquiry phase involved a wide range of data collection techniques to better understand baseline perspectives on and use of modern contraceptives. These included: segmentation research, ethnography, youth participation action research, recruitment of “Young designers” and semi-structured interviews.

“Having young people like myself involved as data collectors ensures that we do not go down a path in which interventions are out of touch with young people’s real needs and day-to-day realities” – A360 Nigeria Young Designer.

2. Insight synthesis (Inspiration)

Disciplinary experts and young analysts worked together to make sense of the research findings. They then used these learnings and research insights to identify new opportunities for intervention design.

“I think we young designers help to interpret the feelings of adolescents—their language, cultural aspects and their identity.” – A360 Ethiopia Young Designer.

3. Prototyping (Ideation)

Teams worked together on “How might we…” design briefs; quickly developing and testing rough versions of potential intervention components. Youth-adult teams were provided with design standards to help them assess the viability of their intervention prototypes.

“We explored different messages from dating to physical health to financial planning. When the team tested a baby cost calculator, we knew we were ushering in the solution.” – A360 Ethiopia Young Designer.

4. Adaptive Implementation

Once final intervention ideas had been developed, they were rolled out incrementally across the A360’s geographic catchment area. As part of an iterative learning process, qualitative and quantitative monitoring and field research data was used to continually adapt the interventions. A challenge to this was finding an optimal fit amidst diverse local and health system contexts.

Key challenges

A360 has succeeded at ‘putting the girl at the center’. But following a process of evaluation, some key challenges were identified:

- The fast-paced, highly iterative nature of human-centred design meant that the decision-making process often went undocumented, e.g. decisions around which design opportunities were moved forward into prototyping and why

- The intensity of inquiry and involvement from young community members meant there was potential for research fatigue, both during the design process and the evaluation

- Focusing too narrowly on what girls want and need sometimes drew attention away from broader, more abstract drivers and constraints, such as gender norms and health systems

- The design process may not have always accommodated or addressed cultural belief systems

Key learnings

The initial findings from the process evaluation of the A360 project show that it is possible to inform and improve health programme decision-making in real-time. However, it also highlighted the need to ensure that interventions adequately meet the contextualised needs of targeted areas. For example, in Ethiopia the process evaluation identified a need to work more closely with the health extension workers so that they were motivated to implement A360.

Evaluation of a human-centred approach such as this is essential but challenging. In the future, those in a position to implement change should allow adequate time to take part in the ‘process evaluation’ and ensure that findings are timed to feed into key decisions. Those leading the process evaluation could consider a joint data collection approach to avoid research fatigue among those involved. Like human-centred design, the process evaluation could also adopt an iterative and adaptive approach and carry out more direct observations to help understand the ‘design energy’, i.e. how decisions were made at key points in the design process.

Next steps

The Adolescent 360 project is still ongoing. To find out more, please visit: www.a360learninghub.org/

If you’ve got any questions for Christina about this project, please email: christina.atchison11@imperial.ac.uk

TALK 2: Matt Walsham (Policy Lead, Partnership for Young London) on ‘Shaping research with young people across the voluntary sector’

WHAT IS PARTNERSHIP FOR YOUNG LONDON?

Partnership for Young London is London’s Regional Youth Unit, providing research training and support for London’s youth sector. It has been funded by the Trust for London for three years, supports over 10 organisations to conduct peer research and provides a model for youth involvement for the voluntary sector. By training up and involving young people in research projects that they have relevant lived experience of, they hope to improve the relevance and output of research and strengthen the youth voice in organisations.

PAST AND CURRENT CASE STUDIES

- Young Harrow Foundation

- In partnership with Northwick Hospital

- Youths provided with research training and then carried out over 50 interviews with clinical and non-clinical staff

- Funding secured to implement change based on the findings

- Barnardo’s

- In partnership with TIGER services

- Working with young people with lived experience of child sexual abuse. Peer researchers always have a support worker with them at every interview, training session or meeting

- The findings will feed into a service redesign

- NHS GO App

- In partnership with NHS and Healthy London Partnership

- Young people involved were provided with additional digital skills to enable them to review the app

- Working with the app developers directly

KEY CHALLENGES

- The nature of working with diverse youth communities means there are varying levels of need, understanding and support. Each new project brings new requirements depending on the youths involved, which puts a lot of time and staffing pressures on those managing the project.

- Despite providing training to the young people in research methodologies and techniques, the research itself can be lower quality than what might be obtained by a more experienced researcher, e.g. leading questions, bias due to own experience. On the other hand, what is collected can be richer and more insightful because youth researchers are more trusted, so people tend to open up.

- There are important ethical considerations when inviting people to get involved in projects that they may find upsetting or distressing to talk or hear about due to past lived experience e.g. sexual assault.

- When working at such a fast-pace – projects are often started and completed within 3 months – there is a danger of being tokenistic, or not representative.

- Young people often want big results – they want to see change. Therefore, it’s important to manage expectations and be clear about the target outcomes of the project. Having something tangible to show at the end is likely to be perceived more positively than reports and hypothetical changes.

MAIN DISCUSSION POINTS

How do you find the right people to involve?

For A360, PSI had already established great relationships with key community leaders so having their trust and buy-in made it easier to reach and engage others in the community. As a result, recruitment wasn’t an issue.

In a similar way, Partnership for Young London have a range of networks and contacts that they approach for projects. The trouble is, seven seems to be the magic number for how many people tend to get involved in projects, but there’s always that question of “how can we ensure these seven are representative of everybody, or all the issues we’re researching?”. Sometimes it’s just not possible.

What does “lived experience” really mean? What qualifies as “lived experience”?

A very valid point from the audience. Sometimes in an attempt to do what feels like the right thing – involving the public in research – there is a risk that it’s done even when it may not be necessary or with people who don’t necessarily have the right experience or insight to offer. Matt advised that one way to test this is to ask, “what lived experience could the public/peer offer that researchers couldn’t provide themselves or learn/research?”. He gave the example of working with youths who’ve lived in certain areas of London and had been involved in gangs, “there are things they know that I could never know or find by searching on the internet”.

If it’s not possible to train up young people/peers to high enough research standards, what if they ‘trained’ the researchers in necessary ‘life skills and knowledge’ instead?

This point was raised in response to the issue that peer research can sometimes suffer from poor research quality. Related to the same point above though, Matt shared that “it’s easier to teach youths core research skills than for them to ‘teach’ me” unique language from local boroughs or cultures. Much of a person’s lived experience and insight can’t be easily captured and transferred for others to adopt and learn from unless they have been working together for a long time.

FURTHER READING

- For more information on the A360 project, visit the A360 website: www.a360learninghub.org/