- My Imperial Global Development Fellows Fund Placement at Imperial

- Researchers and community members working together to shape research on respiratory infections in young children

- HOPE for Hand Osteoarthritis

- Having an Impact with Public Involvement in Paediatric Intensive Care Research

- Public engagement and involvement at the Cardiomyopathy UK conference: When researchers and the public meet

In conversation with: Emma Lidington, PROFILES Trial Manager

Working within/Team name: PROFILES Team, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, The NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research

The value of lived experience

Experts have recommended that academics should actively involve patients and the public in every phase of research to meaningfully incorporate the voice of those with lived experience. However, achieving this goal can seem daunting, particularly as an early career researcher. In our project, the level of patient involvement evolved over the course of the study, with the Public Involvement Research Hub and local funding from my institution as huge drivers of that change.

Our study aimed to explore the care experiences of young adults with cancer aged 25 to 39 and identify unmet supportive care needs through in-depth interviews and an online survey. The gap in research was originally identified by the lead study investigator based on previous work in the Netherlands and clinical experience in the National Health Service. When applying for funding and setting up the project, we consulted patients and public representatives who were funded through our institution on the content of the grant and study materials.

While carrying out the analysis for the first set of interviews, which focused on psychosocial issues, we recognised that our lack of personal understanding of cancer could lead us to misinterpret what people shared with us. To increase the validity of our results and identify the most salient issues that were raised, we informally involved two young adults with lived experience of cancer. We asked the patients to review and input on the themes and subthemes via telephone and email communication and included them as authors on the manuscript. The feedback from the patients was integral in highlighting the positive impacts of cancer, as well as the negative. It also helped to interpret some of the emotional impacts described by participants, such as distinguishing between shame and embarrassment described by some patients based on their own experience. However, we found the lack of resources and structure limited the level of involvement achieved and the impact on the results. We felt unable to ask the patients to undertake time-consuming activities as we lacked funding for reimbursement and communication by email limited the possibility for more active engagement.

An opportunity to do more

When our local Biomedical Research Centre offered patient and public involvement grants, we capitalised on the opportunity to involve patients more formally in the analysis of the second half of the in-depth interviews focusing on healthcare experiences.

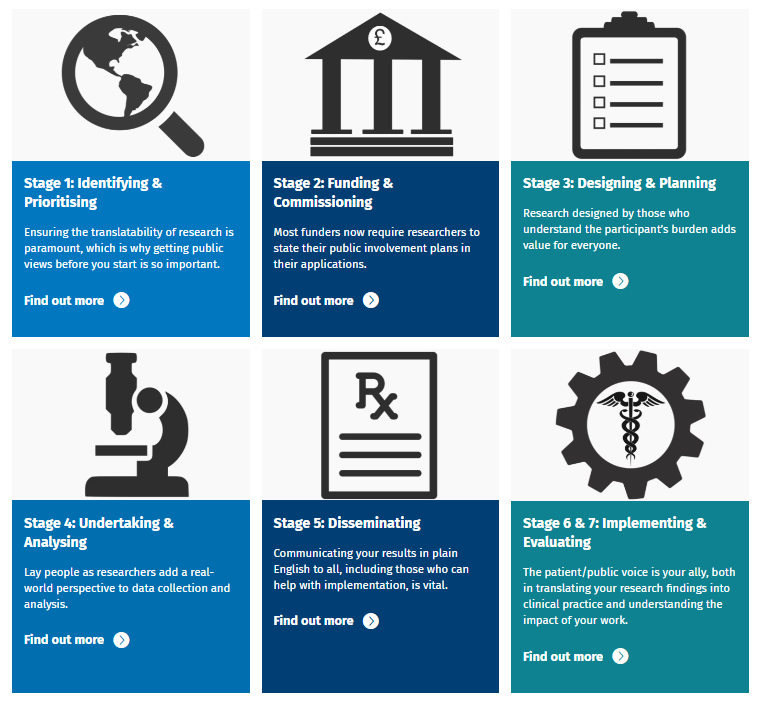

On applying for the funding opportunity, we discovered PERC’s Public Involvement Resource Hub which enabled a much more structured approach to the project. The resource hub offered guidance for involving patients in each phase of research and links to a number of other trusted resources.

Using the information, we identified training materials for analysing interview data through FutureLearn, designed three sessions to analyse the data in an iterative approach, drafted session agendas for a clear roadmap of activities using the template provided and developed an evaluation form based on the National Standards for Public Involvement.

We also built time into our schedule to share materials with patients at least one week ahead of each session following the planning recommendations. We believe that having clear plans for the coordination and evaluation of the project and showing the use of expert resources from PERC in our funding application helped bolster our application. We then teamed up with Shine Cancer Support, a local charity supporting young adults with cancer, to advertise the opportunity to local members and reach a greater number of people than previously possible, making it a fairer opportunity. In addition to authorship on the manuscript, we were able to offer funding for the time and expertise of the patients and potentially support conference attendance to present the work if accepted. The information on the PERC website helped us structure the sessions with agendas and evaluation forms to improve engagement and obtain funding to properly recognise and reimburse the patient experts.

We successfully involved four young adult patients in the analysis of the qualitative data across two in-person half-day sessions and one virtual session. While we faced technical difficulties sharing the excerpts of data for analysis due to the expense of qualitative software, we were able to compress the information in a format that one patient described as “easy to follow/understand”. We also faced practical challenges organising and attending the sessions, particularly during the COVID-19 lockdown, but were able to react flexibly and conduct the final session online. The young adults involved in analysis were essential in highlighting the most important results, shaping the themes and subthemes and choosing the most appropriate terminology from the perspective of someone with lived experience.

Together, the structure and funding enabled more meaningful involvement of young adults and a greater impact on the results of the study. As the researcher, it was satisfying to see how partnering more actively with patients benefitted the study and the findings. Patient provided really positive feedback from the project, reporting that they felt able to contribute, valued, adequately rewarded for their time and that they had an impact on the project.

Even starting small can make a difference

Involving people with lived experience can have a huge beneficial impact, particularly in this type of research where the analysts play a role in understanding and interpreting the meaning of people’s personal experiences. While the goal is to actively involve patients and the public in every phase of research, this shouldn’t put people off from starting wherever they are in the cycle.

Our journey began during the analysis stage by simply speaking to two public partners who were already engaged with the institute, but it laid the groundwork for us to reach and engage new people later down the line.

Authored by Emma Lidington, PROFILES Trial Manager

On behalf of the PROFILES Team, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, The NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research