As part of our blog series for International Women in Engineering Day, Hannah Moran, a Doctoral Researcher in Matar Fluids Group/Clean Energy Process, explores the reasons for the gender gap in science subjects beyond GSCE. She makes the case for raising awareness of engineering as a career option to encourage more young people, particularly girls, into the profession.

It is no secret that women are underrepresented in the UK’s STEM workforce. Despite making up half of the overall working population of the UK, only 24% of the STEM workforce is female [1], and this falls to just 11% in engineering alone. Even these low numbers represent a significant improvement on previous years, largely due to concerted efforts by employers to employ more female engineers and other STEM professionals. However, whilst these recruitment campaigns represent a positive step forward for women in engineering, they are too far down the pipeline to fully address the problem.

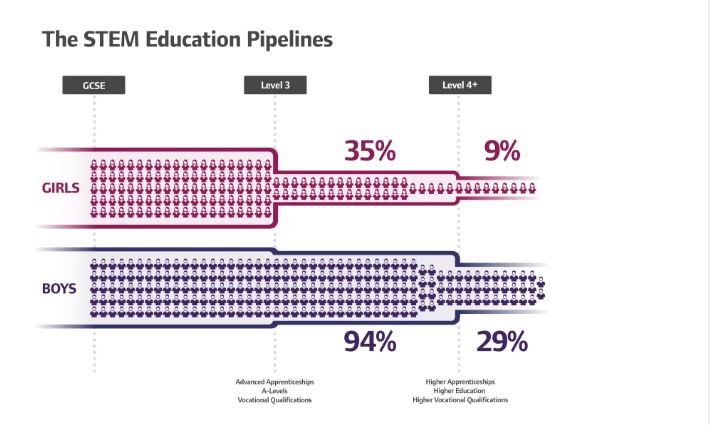

The below figure shows the STEM education pipelines reported by the WISE campaign in 2017. The percentage of girls taking STEM subjects beyond GCSE, where they are no longer mandatory, is significantly lower than that of boys – and there is a further drop in those taking the subjects at degree level. Only 15.1% of UK engineering graduates are female, which has a knock-on effect for employers seeking to recruit a diverse workforce. The key question then is why so few girls are pursuing STEM subjects at A-level and engineering subjects at degree level.

Gender stereotypes are pervasive in our society and affect children from a surprisingly young age – you only need to look at the division of boys’ and girls’ toys and clothing to see the masculine and feminine ideals that children are encouraged to adopt from a young age. A recent study showed that five-year-old girls are just as likely as boys to say that girls can be “really, really smart” but over the age of six they see brilliance as a trait more closely associated with boys. It is shocking and sad that this is the message that young girls are receiving.

These gender stereotypes may be propagated at home, in the classroom, on television shows, in the media, and by peer groups, and it is clear that a societal shift is needed that embraces the idea of all careers being open to all genders. To do this, girls should be introduced to the idea of STEM careers from an early age. I strongly believe that children are never too young to be inspired by science and engineering based activities or to be exposed to role models from these fields. Indeed, the younger the better, so that girls can begin to aspire to STEM career paths before they start to be influenced by stereotypes. A true change, however, requires education of not just children but also their parents. Parents, who have a huge influence on which careers children see as open to them, may not realise the full extent of available career options.

The above is true for all STEM subjects and careers, but I believe engineering in particular requires higher levels of visibility and awareness as a career option in schools. Since engineering is not a standard school subject students often have no comprehension of what an engineering degree, job or career entails. To illustrate the point – when I tell children I’m an engineer, they often ask if I fix washing machines! Raising awareness of engineering from a young age is vital, and the visibility of female engineering role models is key to encouraging more girls aspire to these career paths.

I therefore encourage all engineers, whether male or female, to talk about their jobs to children that they meet, to go back to their old schools to tell children there about the amazing things that they can achieve, to mentor students aspiring to engineering careers and to do anything else they can to raise the profile of women in engineering. It is the responsibility, and to the benefit, of all engineers to address the gender imbalance by championing gender diversity and sharing female role models. By inspiring even one girl at a time, you’ll be doing your bit to close the engineering gender gap.