During the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems globally shifted towards treating COVID-19 infection in adults and minimising use of health services for other patients, including children and young people (CYP), who were less susceptible to severe COVID-19. In March 2020, the NHS recommended remote triaging before any face-to-face contact to reduce infection risk.

The UK Government announced a nationwide lockdown in England from 23 March 2020, and the public was advised to stay at home to limit transmission of COVID-19 and avoid strain on health resources. GPs were asked to prioritise consultations for urgent and serious conditions, and suspend routine appointments for planned or preventive care.

Children’s access to primary care is highly sensitive to health system changes. We examined the impact of COVID-19 on GP contacts with children and young people (CYP) in England. We used a longitudinal trends analysis was undertaken using electronic health records from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) database.

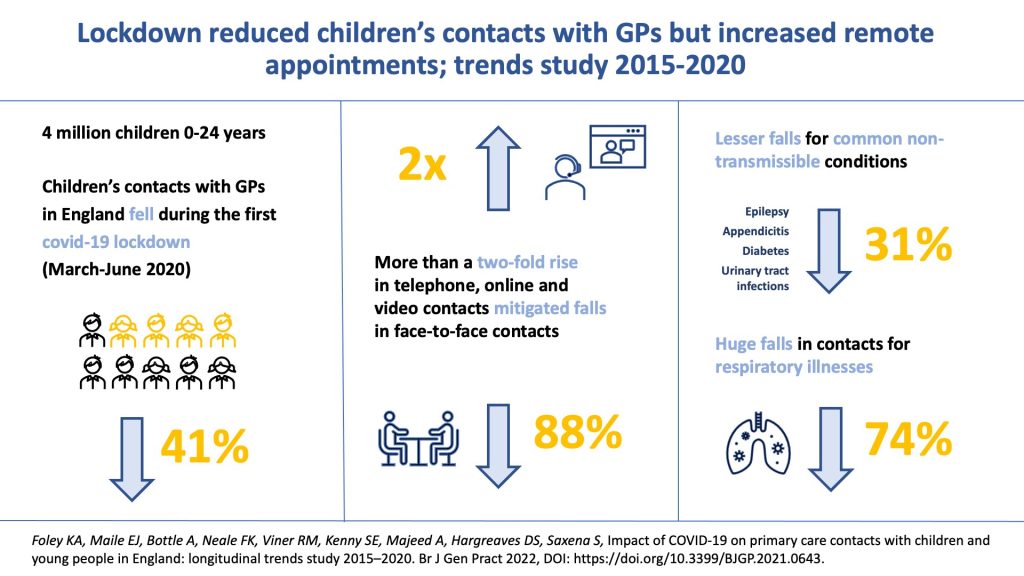

GP contacts fell 41% during the first lockdown compared with previous years. Children aged 1–14 years had greater falls in total contacts (≥50%) compared with infants and those aged 15–24 years. Face-to-face contacts fell by 88%, with the greatest falls occurring among children aged 1–14 years (>90%). Remote contacts more than doubled, increasing most in infants (over 2.5-fold). Total contacts for respiratory illnesses fell by 74% whereas contacts for common non-transmissible conditions shifted largely to remote contacts, mitigating the total fall (31%).

In conclusion, CYP’s contact with GPs fell, particularly for face-to-face assessments. This may be explained by a lower incidence of respiratory illnesses because of fewer social contacts; changing health-seeking behaviour; or a combination of both. The large shift to remote contacts mitigated total falls in contacts for some age groups and for common non-transmissible conditions.

The study can be read in the British Journal of General Practice.