A Silwood Park student team became the champions of a national wildlife competition where they competed to identify as many mammals as possible. Max Khoo from the MSc Ecology, Evolution and Conservation course takes us through the tools of animal investigation that allowed them to emerge victorious!

A new school term began in October 2022. Fresh faces filled the grounds of the Silwood Park campus of Imperial College London once more as Masters’ students were about to embark on their year’s journey. As the leading international centre for research and teaching in ecology, evolution, and conservation, Silwood Park is the ideal place for any ecologist to be surrounded by like-minded individuals.

A group of us – five international students (Sinan Gürlek, Corey Liu, Noel Chan, Hung-wei Lin, and Max Khoo) from the MSc and MRes Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation programme – quickly found common ground in our interest in field surveys and spent our free time looking for animals.

It was soon announced that the annual University Mammal Challenge (organised by The Mammal Society, a UK NGO devoted to the study and conservation of the mammals of the British Isles) would be running again. The challenge took place from November 2022 to March 2023, and involved teams from universities across the UK recording mammals in their campuses. Teams had to gather as many records as possible using a variety of survey techniques across five months and were awarded points based on survey effort.

We had learnt that students from Silwood Park had entered and won the competition in several years during the pre-COVID years.

While none of us have had extensive experience with surveying UK mammals, we were still eager to learn and find out what mammals were calling Silwood Park home and decided to sign up for the challenge, despite knowing Silwood’s legacy of winning! With a large 100-hectare of woodland, bogland, fields, and a lake, it would be certain that this rural campus of Imperial College London would be filled with wildlife.

The challenge required us to use four different survey methods to look for mammals, and we wasted no time sourcing equipment with the support of Dr Catalina Estrada.

Transect surveys

Transects are fixed routes that are visited repeatedly so that observations can be recorded in a standardised format. We had to set up four transects, each 500 m long, within Silwood Park. When walking the transects, we would note down all mammals that we see. It was fairly easy to get started on this, and our team diligently walked the transects. Soon, we realised the campus were filled with wild mammals: European rabbits, grey squirrels, and roe deer were common sight.

However, to locate the rarer species, we needed to devise two new strategies. Firstly, we walked the transects at night as well since some animals are only active then. This allowed us to successfully spot the red fox scurrying around in the woods.

Secondly, we chose to search for semi-aquatic mammals when it was below freezing conditions. The lake in Silwood Park would freeze, and these mammals would be less likely be hiding underwater. With this in mind, I set off one freezing morning in winter and waited by the lake. After 45 minutes in -4°C, I finally managed to catch a glimpse of the American mink hunting for its breakfast by the edges of the frozen lake. Our efforts of waiting patiently in the cold paid off!

Apart from directly observing mammals, we also had to record if we could spot signs of mammals along the transects such as tiny footprints in the mud, or small piles of faeces hiding under tall grass. Learning these signs and how to spot them was not easy so we had to be very observant. Identifying the footprints and faeces was tough as they all superficially look identical. However, the Mammal Mapper phone application by The Mammal Society had a great identification guide to mammal signs, which we could refer to easily.

Camera trapping

Other than physically looking for mammals and their signs on transects, a key research tool for monitoring mammals is to use camera traps. A camera trap is a device used by ecologists to take pictures or videos of animals in their natural habitat. When an animal walks by in front of the camera, it is triggered, and a photo or video is taken. This allows researchers to identify and study the animal without being physically present.

To maximise the chances of capturing more mammals, we decided to set up cameras in locations where animals are known to pass through. As such, we went out into the woods looking for paths that mammals use regularly or their dens.

While looking for ideal camera locations, we chanced upon a European badger sett (i.e. a badger den). However, it was still winter, and the badgers were likely still hibernating. We waited until February to deploy our camera at the entrance of the sett.

Our intuition was right, and our patience paid off! We managed to capture a photograph of this mammal that we would otherwise not have been able to see physically as they are extremely elusive and nocturnal. Apart from badgers, we also managed to photograph many other different animals: red fox, roe deer, muntjac, and even a tawny owl hunting a rodent!

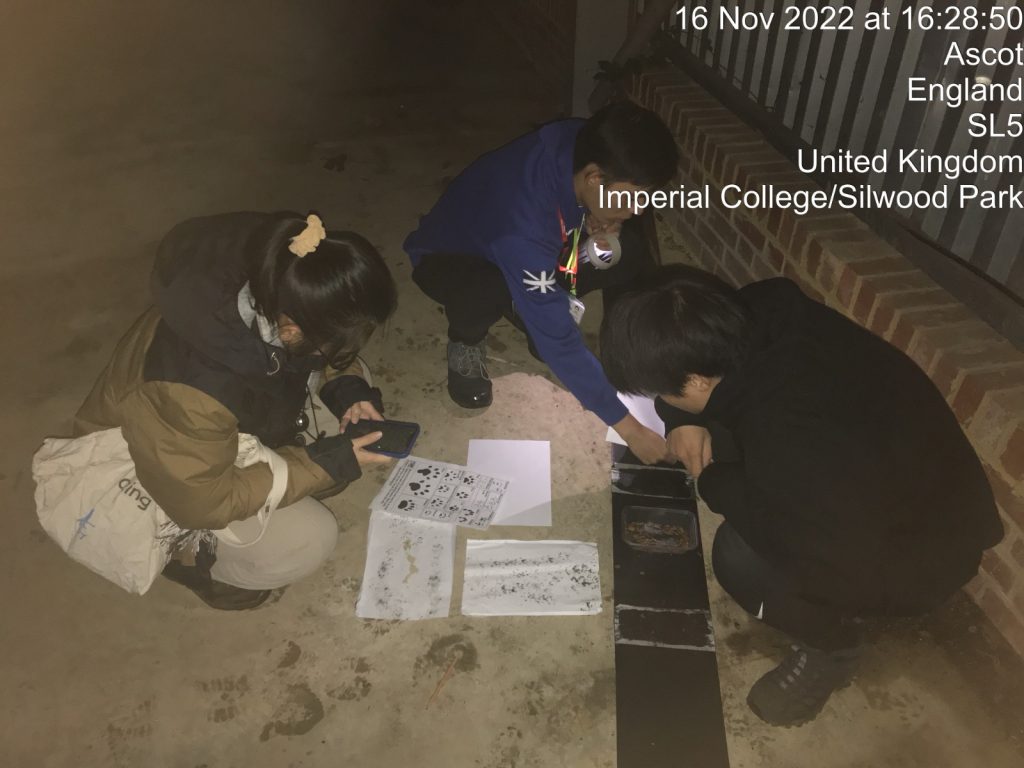

Footprint tunnels

The third survey method we used was deploying footprint tunnels. These tunnels are used to detect small mammals by placing ink on a piece of paper inside a tunnel, which captures the animal’s footprints as it passes through. The resulting footprints can be used to identify the species. This is especially useful for surveying rodents as it is hard to identify rodents using other methods.

This survey method was the method where our team had the least success. The footprints all look superficially identical, and we had difficulty identifying them. Nevertheless, we still managed to identify a couple of species.

Audio surveys

To survey flying mammals (i.e. bats), we had to carry out audio surveys. This involved using ultrasonic bat detectors to detect or record their echolocation calls. Such a method is required as their calls are beyond the range of human hearing. Depending on the frequency of the detected calls, the species can be determined.

The learning curve for surveying bats was steep: we had to learn how to operate new and complicated equipment, survey the bats at the right timing and locations (different species are active at different times of the night at different habitats), and analyse the data. Fortunately, we had the help of our colleagues who are experts in the field, and we managed to detect some bats!

The long duration of the challenge meant that our team had to be consistent with our surveys. This was despite having to attend classes, work on our dissertations, and even study for exams. Still, the team put in a lot of hard work, and we managed to record 14 species in total.

We are very fortunate to have a hands-on opportunity to survey mammals in the field as it is a quintessential skill for any budding ecologist. Now equipped with these new skills and a deeper familiarity with the UK’s mammals, we are ready to enter a career in conservation or further our research in this field. Overall, we thoroughly enjoyed ourselves, and it was the icing on the cake that we emerged as the champions!

We are grateful to Dr Catalina Estrada for her support on our challenge and facilitating the loan of survey equipment, and Dr Cristina Banks-Leite and Dr Jenna Lawson for the loan of Audiomoth. We would also like to thank Emma Little for guiding us on bat survey techniques.