Alice Day is a PhD student at the Waring Lab and the Fisher Lab within the Department of Life Sciences. She researches the potential of fungal inoculations in restoring agricultural land. In this blog post, she discusses how modern agriculture has depleted our soils of the microbes that once made them thrive, and how we may one day re-introduce them.

The hidden complexity of soil

Dirt, mud, muck – all words we use to describe soil. What these words don’t capture is the astounding diversity of life that inhabits our soils and the extreme complexity of the interactions that go on beneath our feet every single day.

Most of this diversity consists of microbes like fungi, bacteria and viruses that work together, forming relationships to carry out essential functions. Fungi, in particular, play a role in maintaining soil health and fertility.

Saprotrophic fungi – the waste recyclers – secrete enzymes, working as the soil’s stomach to decompose organic matter, releasing nutrients back into the soil. Mycorrhizal fungi form underground networks – often called ‘the wood-wide web’ – acquiring water and nutrients using their thread-like fungal hyphae and producing glomalin, a sticky glycoprotein that stabilises the soil. Pathogenic fungi also lie in wait – these can be plant, animal or human pathogens that keep the ecological balance in check.

Plants cannot move, but luckily, these microbes – fungi alongside bacteria and viruses – form symbiotic relationships with almost all plants, including the crops we rely on, providing them with an increased network to acquire nutrients and water and to fend off pests and pathogens in exchange for carbon. Interactions between microbes and the host plants they surround are so fundamental that they can be thought of as one whole interconnected system, termed a ‘holobiont.’

The decline of soil microbial communities

Holobionts in agricultural landscapes are under threat, but to understand how we got here, let’s rewind. The story begins with the Haber-Bosch process, initially developed for fertiliser production but repurposed for bomb-making during World War I. By World War II farmers were encouraged to apply synthetic fertilisers and other agrochemicals liberally to boost crop yields and keep pests and pathogens at bay, securing the UK’s food supply. This era, spanning wartime and its aftermath, became known (perhaps ironically) as the “Green Revolution.”

Repeated excessive use of agrochemicals over decades has caused the communities of microbes that inhabit our agricultural soils to shift and die. Fertilisers flood soils with nutrients reducing the need for nutrient foraging fungi so crops stop recruiting their symbiotic fungal partners, leaving the fungi to die.

Broad-spectrum fungicides, designed to kill fungal pathogens, are not specific, so also disrupt and kill beneficial fungi by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis, a key component of cell membranes, blocking ATP production or disrupting metabolism.

Our soils have become so degraded that farmers have to rely on chemicals to grow their crops and fight off crop diseases. We’re now reaching the point of a hypothetical yield ceiling, where crop yields fail to rise even if we use more fertilisers due to a complete lack of foundational soil health.

Harnessing the power of microbes

It is in this bleak depiction of our soil health that I see massive potential for restoration to have a visible impact on the world around us and beneath us. The potential lies in reintroducing beneficial microbes back into degraded soils, a concept that scientists have been exploring for decades.

Initially, researchers focused on single-species inoculants, a product comprising of a single species of bacteria or fungi designed to enhance crop performance. However, single-species inoculants often don’t survive or produce any lasting beneficial effect as they fail to establish in the complex soil environment.

Inoculants consisting of one or a small mix of microbial species may be capable of fine-tuning healthy ecosystems, but we cannot expect a single microbial species (out of the 1 trillion that inhabit the earth) to do all the work by itself. That’s where my work comes in.

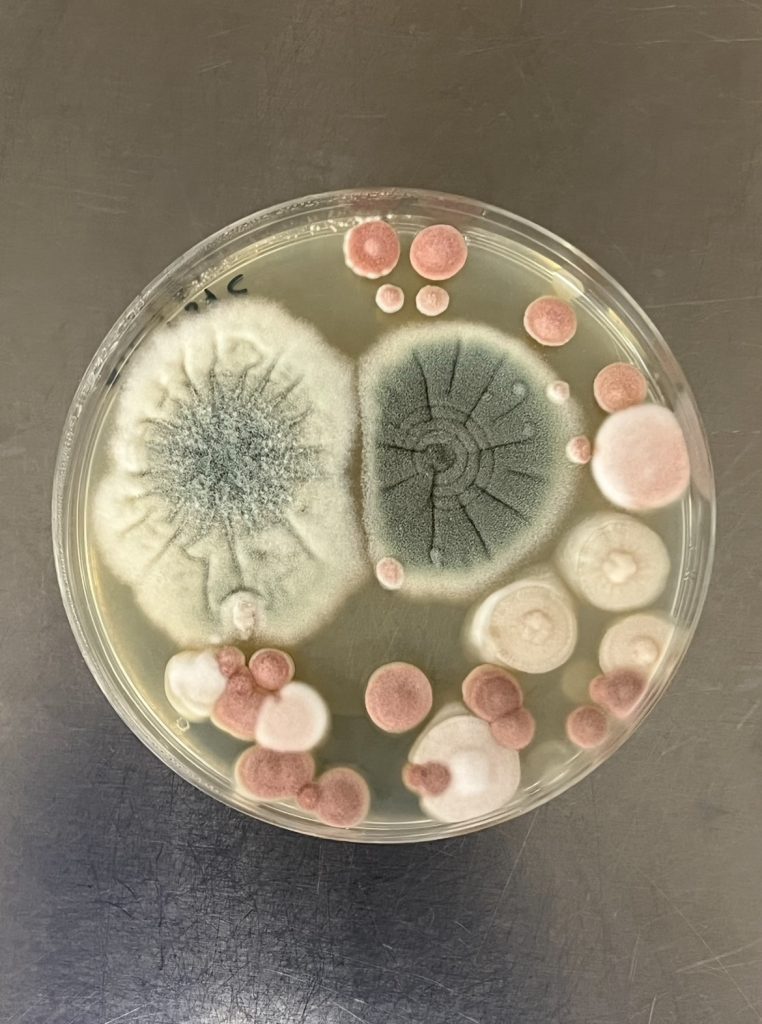

My PhD project is placed across two labs at Imperial that cover what I like to call the good, the bad and the ugly of the fungal kingdom. The Waring Lab, run by Bonnie Waring, investigates how we can use beneficial members of the fungal community to restore and enhance ecosystems.

Meanwhile, the Fisher Lab, run by Matthew Fisher, focuses on emerging fungal pathogens to understand how environmental factors such as fungicides used in agriculture or clinical antifungals lead to the evolution of antifungal resistance that threatens both food security and human health.

My research spans these two areas, where I delve into the impacts of agrochemical use, specifically fungicides, on beneficial and pathogenic fungi and investigate a potential method to restore our degraded agricultural land.

The promise of soil transplants: a path forwards for sustainable farming?

Soil transplants involve taking soil from a healthy donor site and applying it to a degraded receiver site in the hopes of shifting the microbial community towards that of the healthy donor. My research aims to identify key soil characteristics that promote crop yields whilst selecting resilient microbial communities that can recover after stresses, such as fungicide use or survive in the face of climate change.

In reality, my research involves me being covered in soil or repeating the same protocol in the lab for weeks. My first experiment involved collecting 48 soils from farms and natural habitats across the UK. I then grew wheat in these soils under controlled conditions, applying fungicides and monitoring how the plants responded.

DNA sequencing of soil samples, specifically ITS2 metabarcoding, identifies fungi, allowing me to map the fungal community composition and identify the most beneficial soils for crop yields and health.

Thankfully, all of my wheat plants survived – always a relief in research! Using yield data, I have selected 2 ’bad’ and 2 ’good’ soils to serve as ‘donor’ soils in my next phase. Now, I’m scaling things up. Armed with 200kg of soil from each site, I’m preparing for a field trial, where I’ll put the soils and their microbial communities to the test under real world conditions, spreading each donor soil on randomised plots on an agricultural field and planting wheat, this time outside and open to the elements.

This area of research is still in its infancy, with many unknowns and challenges. We now need determine what characterises a ‘good’ donor soil, how to best match donor and receiver sites, create a method to sustainably amplify the donor soils, quantify the risks of introducing foreign microbes and understand if transplanted soils persist in the long term.

The list is long, but maybe after all of these questions are answered we may have a robust, nature-based approach to restore our degraded agricultural soils, help farmers transition to sustainable farming and ensure our food security. My hope is that uncovering the secrets of the soil could be one key to unlocking a more secure and resilient future for food production, simultaneously benefitting people and the planet.