PhD student Pulkit Ghoderao describes how studying the structure of ice cream can help us understand the structure of the Universe.

That seems like an extraordinary thing to say, really, what has our universe got to do with the fluffy goodness that is ice-cream?! And where are we coming up with these out-of-the-world comparisons in the first place?

The answer to the second question is straightforward, the comparison arises naturally as we examine the initial conditions and follow the evolution of our Universe according to the laws of physics.

This is what I do as a PhD student at the Department of Physics’ Theoretical Physics Group at Imperial. I specialise in the physics of the early universe.

As a theorist, my research involves translating physical phenomena into the language of mathematics, solving equations and performing computer simulations. As such, I do not set up experiments or work with observational data, but the one powerful tool which I do have is that of the thought experiment.

Let me share an example.

Thought experiment: the humble tool of the theory-minded

Imagine we have a photo of the Earth on a mobile device. Upon zooming out the image, what do we see? Well, if we zoom out enough we should be able to see our neighbouring planets Venus and Mars. Zooming out more, we see the entire Solar System comprising of eight different planets orbiting the Sun.

Continuing, we see our Milky Way Galaxy, that is made up of many, many different stars like our Sun. Zooming out even further, our neighbouring Andromeda Galaxy starts to enter the picture, followed by a cluster of different galaxies.

Let us keep going. We now see a bunch of different galaxy clusters, but it is getting harder and harder to distinguish them from each other. Eventually, once we have zoomed out extremely, so that one pixel in our image corresponds to a distance of 100 Mega parsecs (i.e. a hundred billion trillion kilometres), we are not able to distinguish any individual matter at all.

The universe starts to look the same in all directions and at every position. This is where the domain of cosmology begins.

Cosmology

Cosmology is the study of the Universe as a whole instead of its constituent parts like galaxies, stars, planets… It is a subject that formally emerged as a distinct sub-field of physics in the 1900’s when experiments first began to be able to look at distant objects in our cosmos and map out how those objects were arranged in it.

However, as a field of enquiry, cosmic questions have been asked for as long as humanity has existed. All of us must have wondered at some point in our lives: where do we come from; what is our place in the Universe; how did it all begin; and how will it all end? Cosmology seeks to satiate this thirst for human curiosity.

The particular branch of cosmology that I study aims to answer questions like: Can we know what kind of particles were there at the very beginning of our Universe? Can we figure out how they interacted with each other, for example by looking at their imprints on the distribution of galaxies or temperatures we see today? And can our observations today tell us something about the strength of interactions between those particles?

Typically such an investigation starts by writing down all possible interactions between particles that we believe are necessary to satisfy the symmetries of physics. For example, if two particles interact on one side of the Universe, they should interact the same way if we placed them on the other side of the Universe. This is a type of symmetry, known as ‘translation symmetry.’

Symmetries are another powerful tool that help theorists like me to express physical phenomena in terms of their core mathematical structure. For instance, we have seen using the tool of the thought experiment that the universe looks the same in all directions and at every position. These are also types of symmetries known as ‘isotropicity’ and ‘homogeneity.’

By combining these symmetries with the observation that our universe is expanding, we are left with only three distinct types of geometry which the Universe can have! This is a massive simplification and allows us to make a great deal of progress to describe the Universe’s evolution.

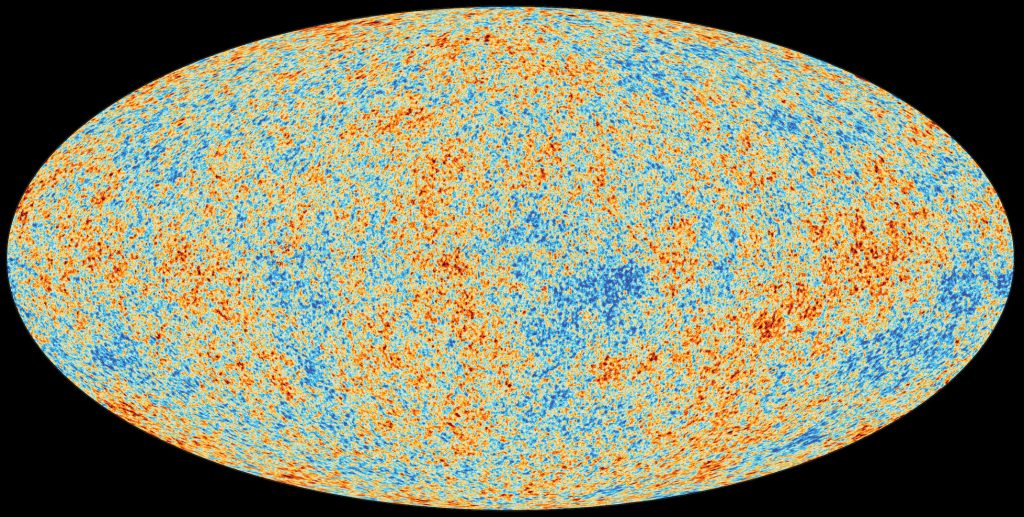

We follow the evolution of the Universe and the particles in it using the laws of quantum mechanics and general relativity. By studying how they affect the distribution of galaxies and temperature in the universe, we are able to determine precisely how strongly or weakly these particles interact with each other.

Physics of ice-cream: yum!

There can be a feeling, especially amongst students, that theoretical physics involves so much mathematics that current research is far removed from the realm of everyday experience. This might seem to be the case from the discussion so far, but is not true! Many of our theoretical ideas have similarities with everyday phenomena. For example, ice cream!

Ice-cream has three main ingredients: air, water and milk (plus sugar and flavouring of course, or it might turn out rather bland!). If we first consider a mixture made of only air and water, we see that as the air temperature drops, water starts to freeze by forming bubbles of ice that expand and eventually meet and percolate to form a solid block of ice. This changing of state from liquid to solid is also called a phase transition.

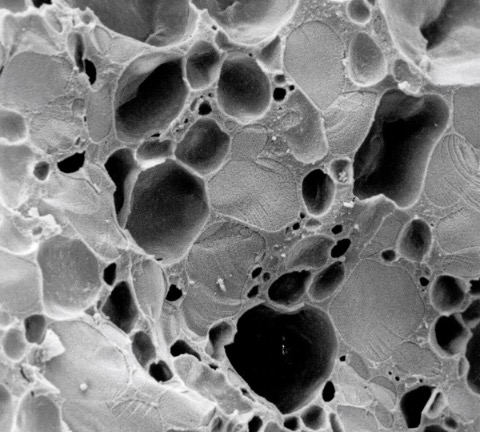

Now if milk particles (aka lactose molecules) are also present, they are more concentrated in some places and less in others. So when the air temperature drops, the water freezes at slightly different times at different locations, resulting in bubbles that look something like Figure 1. This is what gives ice-cream its fluffy texture.

Our thought experiment at the start has shown that the Universe looks the same in every direction and at every position, when we zoom out sufficiently. This is similar to water, which we know is made up of many, many individual H2O molecules. When we look at water from our zoomed out perspective, it looks like a homogenous fluid. Similarly, seen as a whole, the Universe also looks like a fluid despite being made up of galaxies, stars, planets and us.

One of the most popular theories of the early Universe is that it underwent a period of rapid inflation where the size of Universe expanded very, very quickly. As it expanded, it cooled.

This is where our idea of the universe as an ice-cream comes in. As the temperature cools down, the Universe could also have transitioned from one state to another, like water transitioning to ice. Plus, during the period of rapid expansion, the universe need not be made up of only one type of particle. In fact it can be thought of as a mixture of two fluids, just like water and milk in ice-cream!

And so, with my supervisor Arttu Rajantie at Imperial and our collaborator Björn Garbrecht at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), I showed a proof of principle that we would be able to detect a significant effect in the distribution of galaxies and temperature today if our Universe was indeed like an ice-cream (i.e. if it underwent a phase transition during cosmic inflation).

In doing so, we developed a general method by which anyone can take their favourite particle physics model, and if it has the right ingredients to undergo a phase transition during inflation, then by following our method be able to constrain the particle interaction strengths in their model through cosmology experiments in the near future.

Now is an exciting time to be doing cosmology, because we have many new experiments lined up over the next decade that would be able test many of our speculations. For example, later in the year, NASA is set to launch its SPHEREx mission that would precisely measure the galaxy distribution in our universe. Then we can put our theoretical idea of the universe being an ice-cream to the test by comparing with what it finds. Stay tuned!