PhD student Michel Valette explain how multi-scalar and inter-disciplinary research could support adaptation to emerging wildfire risks and the development of integrated fire management policies.

In January 2025, the Los Angeles wildfires captured the media spotlight, partly due to the widespread destruction in urban areas, the risks to human life, and the astronomical costs associated with the wildfires. The Los Angeles wildfires add to a growing list of wildfires that have made headlines in recent years, such as the 2023 Canadian wildfires, the 2022 European wildfires, and the 2019–2020 Black Summer in Australia.

These wildfires crisis covered by the media are only the tip of the iceberg: the state of wildfires report reveal changing and intensifying wildfires in many other regions of the world. Brazil, a country roughly the size of Europe and home to a significant portion of global biodiversity, is no exception. Over the last few years, the country has experienced several major wildfire events, such as the 2020 wildfires that burned 30% of the Pantanal biome (the largest tropical wetland), the 2024 wildfires in the state of São Paulo, or recurring wildfire crises in the Amazon that sometimes shrouds cities thousands of kilometres away in smoke.

When we can’t fight fires, we need to learn how to live with them

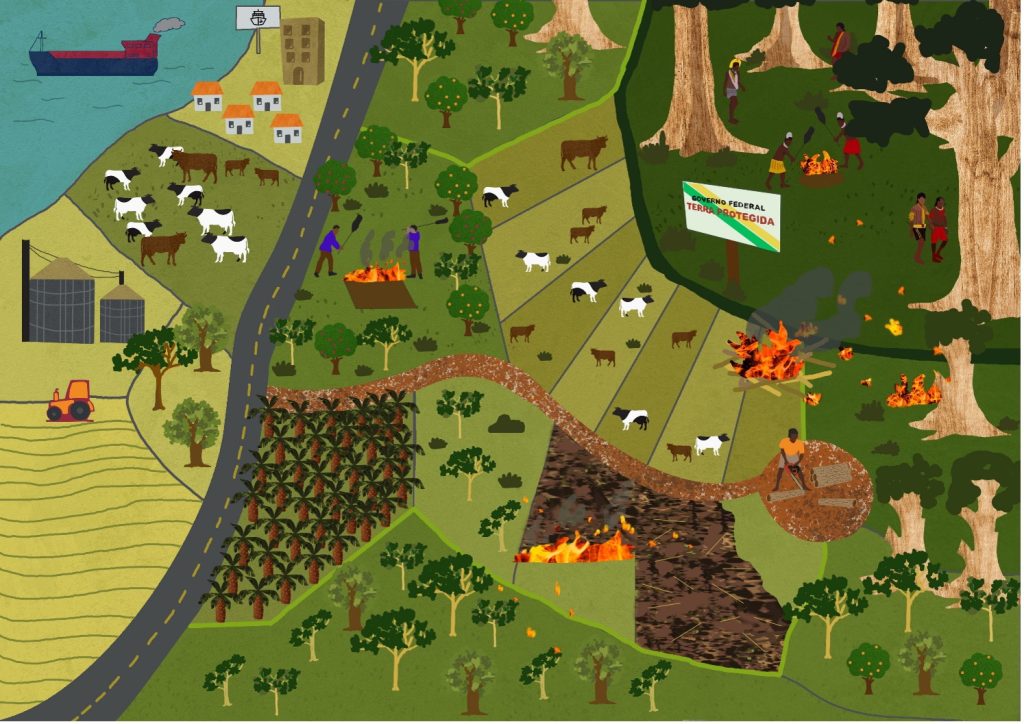

Historically, fire management rely on the exclusion of fire from the landscape, by criminalising most fire use and fighting any wildfires burning. Faced with the persistence of wildfires and an increasingly obvious failure of fire exclusion, several countries are embracing a different approach, including Brazil.

In 2024, Brazil passed a national law supporting an integrated approach to fire management that promote burning practices of Indigenous and traditional communities and support establishment of local fire brigades to adapt to new wildfires risks.

I’m a PhD candidate at the Centre for Environmental Policy and the Leverhulme Wildfires Centre investigating changes in in the Brazilian Amazon and how local communities are adapting. Using different sources of information, such as satellite images, climatic data and interviews with local communities, I explore the challenges these communities face and the opportunities available to adapt to shifting wildfires risk.

Understanding how to limit the environmental damage caused by wildfires in the region is essential, as carbon emissions from wildfires Wildfires are also preventing the adoption of certain agricultural systems and having severe impacts on the health of local communities.

Understanding drivers of change at a regional level

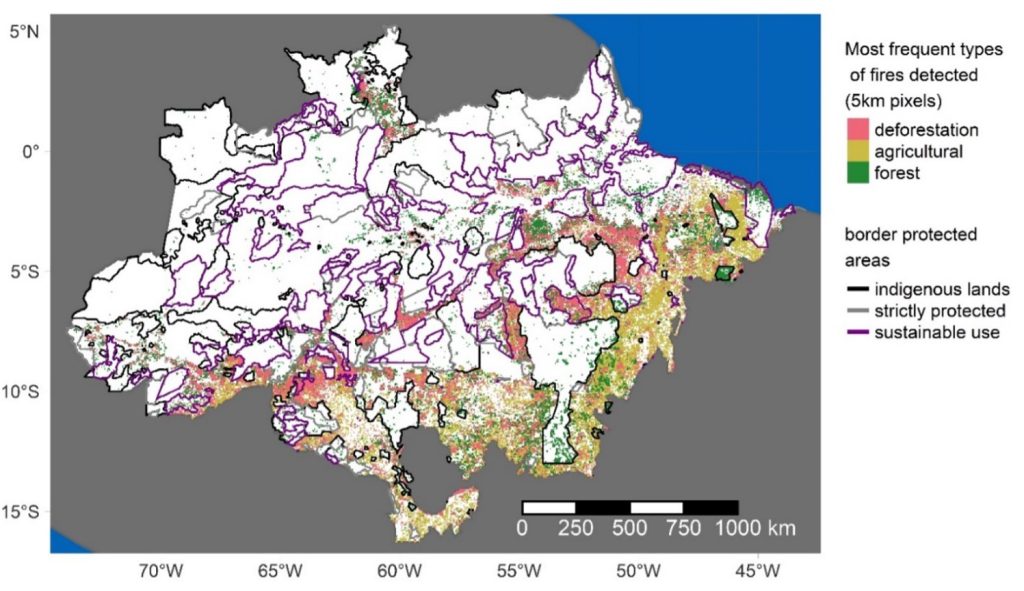

Using deforestation and land-use maps, I classified fires detected by satellites into several categories and then used models to understand the key drivers behind in the Brazilian Amazon between 2009 and 2021. I found that agriculture was a major driver, with pasture being linked to most fire use for deforestation and agricultural land management, while perennial crops were associated with a decline in all fire types, especially in recent years.

A more concerning finding was the increasing number of fires and wildfires deep within forests, far from agricultural land and well-connected regions of the Brazilian Amazon. This ‘interiorisation’ of fires could threaten previously unaffected forests, that lack crucial adaptation which could help trees survive wildfires.

However, I noticed that areas that were protected for conservation or were designated as Indigenous lands were associated with fewer fires, highlighting the role of traditional and Indigenous communities as well as the protected areas network to preserve the Amazon forest from wildfires.

Co-constructing knowledge on locally changing fires regimes

Though the findings from my modeling work provided useful insights, they were only one piece of a bigger puzzle. To guide environmental policy, we need to consider local context and practices for adaptive fire management.

I had an opportunity to collaborate with indigenous practitioners from the Raoni Institute and a local fire brigade of the Capoto/Jarina Indigenous Land, located in the north of Mato Grosso, a region of the Amazon experiencing severe wildfires. Habitants of the Capoto/Jarina have grown increasingly concerned as the fires they use for different activities, such as agriculture and hunting, are becoming increasingly dangerous.

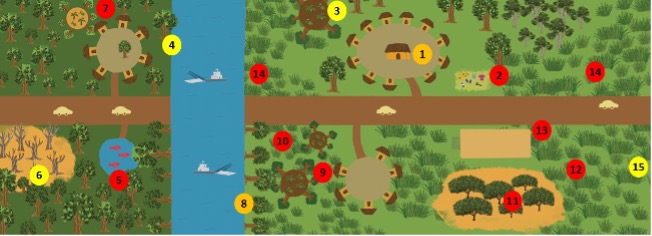

Building on my expertise in quantitative analysis and my interest in inter-disciplinary research, I designed a project that relies on a mix of methods. I used quantitative climate models and satellite images to assess changes in wildfire risks over extended periods, while also using social science methods to examine the intricate relationships between detailed traditional ecological knowledge, fire use, and adaptation strategies to wildfire risks.

Global climate models show a heightened wildfire risk toward the end of the dry season, when residents of Capoto/Jarina traditionally use fire to clear their swidden fields. These findings align with local observations: participants reported that the onset of the rainy season had become increasingly unpredictable, partly due to shifts in bio-indicators used to anticipate seasonal changes.

They also reported that “the rain is lying”. In other words, rainfall can often be followed by weeks of dry weather, when before, the first rain would quickly followed by other showers.

Changes in vegetation and its interaction with traditional fire use are also significantly affecting wildfire risks. One study site has been invaded by brachiaria grasses, an exotic species used for pasture outside Indigenous land that is highly flammable. A mapping exercise I conducted with participants revealed that this vegetation shift has created high wildfire risks in several areas, especially where traditional fire practices for agriculture and other livelihoods intersect with the spread of these grasses.

But participatory mapping also revealed how local communities use fire selectively in different vegetation types to maintain a diverse habitat that supported biodiversity and community needs. Including these local communites’ rationales for fire use will be crucial for strengthening traditional fire governance systems and making fairer fire management decisions.

Supporting national policies for integrated fire management

Brazil’s new laws on fire managements support the creation of local fire brigades and community efforts to tackle wildfires. I compiled my results into a report and a poster that could be used for discussions within communities. From my research alone, I identified a diversity of factors influencing wildfire risk that could affect future fire management, all within the same Indigenous land. My results highlighted the need for locally adapted analyses and tailored adaptation strategies.

By integrating multiple geographical scales and sources of information, my research offers a more comprehensive picture of fire dynamics and aligns it with local fire-use practices for both livelihood and cultural purposes within Indigenous lands. As Brazil’s fire management policies continue to evolve, local fire brigades like the one in Capoto/Jarina are expected to play an increasingly prominent role. Understanding shifting fire regimes and the appropriate methodology to assess them is critical for supporting them and more broadly communities that need to deal with shifting wildfires risks.