This is the text of the first year cellular pathology course lecture which I am giving tomorrow.

I hope that it might act as a focus for interaction with the students.

The Pathology of Neoplasia

Tumour: Any kind of massforming lesion. May be neoplastic (see below), hamartomatous (see below) or inflammatory (e.g. nasal polyps).

Neoplasm: The autonomous growth of tissue which have escaped normal constraints on cell proliferation.

Neoplasms may be either benign (remain localised) or malignant (invade locally and/or spread to distant sites).

Cancers are malignant neoplasms.

Hamartomas are localised benign overgrowths of one of more mature cell types e.g. in the lung. They represent architectural but not cytological abnormalities. For example: lung hamartomas are composed of cartilage and bronchial tissue.

Heterotopias are normal tissue being found in parts of the body where they are no normally present. For example: pancreas in the wall of the large intestine.

Important to note that many malignant tumours rarely cause death (especially skin cancers) and that some benign tumours do kill (usually because of their location, e.g. the brain)

Classification of neoplasms

The primary description of a neoplasm is based on the cell origin and the secondary description is whether it is benign or malignant.

For example, tumours of cartilage are either chondromas (if benign) and chondrosarcomas (if malignant.) The “chondro” stem means derived from cartilage the suffix “oma” means a benign tumour and the suffix ”sarcoma” means a malignant (soft tissue) tumour.

Type of epithelium Benign Tumour Malignant Tumour Example(s)

Squamous Squamous epithelioma or papilloma Squamous cell carcinoma Skin, oesophagus, cervix,

Glandular Adenoma Adenocarcinoma Breast, colon, pancreas, thyroid

Transitional Transitional papilloma Transitional cell carcinoma Bladder

Type of connective tissue Benign Tumour Malignant Tumour Example(s)

Smooth muscle Leiomyoma Leiomyosarcoma Uterus, colon

Bone Osteoma Osteosarcoma

(Osteogenic sarcoma) Arm, leg

Haematological neoplasms Benign Tumour Malignant Tumour Example(s)

Lymphocytes Extremely uncommon Lymphoma Lymphoma

Stomach

Bone marrow Extremely

uncommon Leukaemia Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia,

Chronic myeloid leukaemia

Teratomas

These are tumours derived from germ cells and can contain tissue derive from all three for 3 germ cell layers. They may contain mature and / or mature tissue and even cancers.

Malignant tumours with the suffix “oma”:

1. (Malignant) Lymphoma

2. (Malignant) Melanoma

3. Hepatoma (better called liver cell cancer).

4. Teratoma (not all, see above)

What are the differences between benign and malignant tumours?

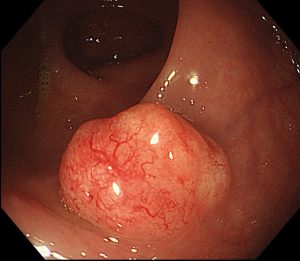

1. Invasion: This means direct extension into the adjacent connective tissue and /or other structures e.g. blood vessels. This is what distinguishes dysplasia/ carcinoma in situ from cancer (see next lecture).

2. Metastasis: This means spread via blood vessels etc (see below) to other parts of the body.

NB All malignant tumours have the capacity to metastasise although they may be diagnosed before they have done so

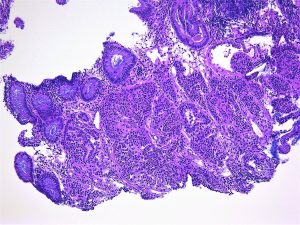

3. Differentiation: This means how much do the cells of the tumour resemble the cells of the tissue it is derived from.

Tumour cells tend to have larger nuclei (and hence a higher nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio) and more mitoses than the normal tissue they are derived from. They may have abnormal mitoses (e.g. tripolar) and marked nuclear pleomorphism (variability in nuclear size and shape).

4. Growth pattern: This means how much does the architecture of the tumour resembles the architecture of the tissue it is derived from.

Tumours have less well defined architecture than the tissue they are derived from.

It is important to note that benign tumours may become malignant.

By which routes do tumours spread?

1. Direct extension. This is associated with a stromal response to the tumour. This includes fibroblastic proliferation (“ a desmoplastic response”), vascular proliferation (angiogenesis) and an immune response.

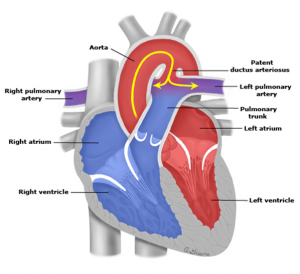

2. Haematogenous (via blood vessels). The blood vessels usually invaded are the venules and capillaries because they have thinner walls. Most sarcomas metastasise first via the blood vessels.

3. Lymphatic (via lymphatics to lymph nodes and beyond) The pattern of spread is dictated by the normal lymphatic drainage of the organ in question. Most epithelial cancers metastasise first via the lymphatics.

4. Transcoelomic (seeding of body cavities). The commonest examples are the pleural cavities (for intrathoracic cancers) and the peritoneal cavities (for intra-abdominal cancers)

5. Perineural (via nerves) This is an underappreciated route of cancer spread.

How do we assess tumour spread?

1. Clinically

2. Radiologically

3. Pathologically

How do we describe tumour spread (stage)?

T= Tumour: the tumour size or extent of local invasion

N= Nodes : number of lymph nodes involved

M = Metastases: presence of distant metastases

This is called the TNM system and the details are different for each kind of cancer

Grade = how differentiated is the tumour (see Differentiation, above)?

Stage = how far as the tumour spread (see TNM above)?

In terms of tumour prognosis, Stage is more important than Grade.

Read Undergraduate Pathology: The Pathology of Neoplasia in full