PhD student Jarmo Kikstra from the Centre for Environmental Policy reflects on the challenges of defining a just transition away from fossil fuels. His research as part of the Science and Solutions for a Changing Planet DTP at the Grantham Institute helps quantify elements of climate justice.

International policy discussions on the environment and international development talk a lot about the need for a just transition. Great! Who doesn’t want a transition to be just?

And we know quite well what a just transition should look like. Right? Or, wait, do we really know?

Thinking about the future is not easy, and the concept of justice has many interpretations. Luckily, we have (quantitative) tools to help us sketch out and examine possible scenarios. Research like mine aims to inform the global just transition debate, moving towards measurable targets for a just transition with decent living standards for all.

What is just? Baby don’t hurt me, no more.

Let’s see… A just transition is a transition that protects the vulnerable; ideally, nobody should be hurt. A just transition places the burdens on those with the strongest shoulders. A just transition helps those who cannot afford the emissions reductions or adaptation measures. A just transition recognises and corrects historical wrongdoings. A just transition involves all relevant stakeholders and uses all available knowledge in the transitioning process. And a just transition makes sure to help out the people whose livelihoods are affected. And we can go on.

“See?” you may say, “We know quite a lot.” Maybe we don’t need these complicated new models after all. But when we get more specific, it always gets muddier. Always.

Let’s look at China. Like other countries, it should phase out coal in order to meet ambitious targets. But should China phase out its coal by 2040? Or 2035 or 2030?

In richer countries, we need to look beyond making the supply of energy renewable, and figure out: how much can we reduce energy demand?

These questions all focus on the need to reduce emissions, which is an unavoidable part of halting climate change. But a just transition is broader than climate change, and climate justice links to many other large societal problems, like poverty and current resource distributions.

To add to that, climate change is already here, and impacts beyond the limits of adaptation are real – a just transition thus needs to correct for loss and damage.

What can we know?

How can we ever look at all possible factors in justice, for all countries of the world?

Truth is: we can’t – perfect solutions do not exist.

In the international climate debate, hundreds to thousands of people work on creating and implementing international climate agreements, as well as translating them into national climate policies and regional or sectoral targets.

Some of their work is informed by researchers who try to create accurate and detailed descriptions of many possible climate futures. This field combines information from many disciplines into what is called integrated assessment models (IAMs).

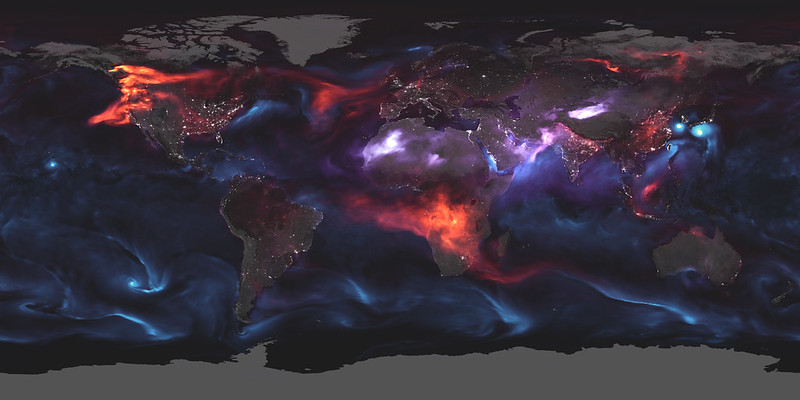

IAMs are global models, with regional resolution, that model the transition to net-zero (and beyond that). They describe the processes of an energy transition, changes in land-use and agriculture, and lots of things connected to that (air pollution, climate change, water consumption, etc.). With this, they try to inform policymakers about the ways climate change can be tackled today and in the decades ahead.

They have been used most influentially as detailed descriptions of so-called ‘emissions scenarios’ (i.e. possible pathways that human society may take, including mitigation measures, and their resulting greenhouse gas emissions).

Examples include reaching net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, or halving global emissions by 2030, which have both been informed by IAM studies. They both relate to the goal of keeping warming to 1.5C, which is part of the Paris Agreement: a legally binding international treaty on climate change adopted in 2015.

Research with IAMs played a role in showing possible pathways limiting warming to 1.5C, helping it to be adopted as an internationally agreed political goal.

Right now, we have global goal, informed by our predictions of local climate damages and irreversible climate impacts. But, less is clear on how different regions should contribute to achieve this overarching global goal.

For what is regionally just, in the context of a global climate target, is more difficult to determine. One reason for this is that it is dependent on more difficult, political and normative judgements.

Does this mean that science doesn’t have a place in a just transition? Not at all!

There’s an enormous need for scientific information to base regional targets on. Since the Paris Agreement, countries regularly need to submit their plans for national climate action, known as ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDCs), to the United Nations. During COP28, all member countries reaffirmed that “each Party’s successive (NDC) will … reflect its highest possible ambition”.

This means that the scientific community should work hard to try to provide guidance on where such regional and national ‘highest possible ambitions’ lie, taking into what is possible to implement in each country . And that same sentence goes on to say “… reflecting its common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.” In other words, not all countries can be expected to do the same: some can and should take more action.

Some elements of a just transition

Dealing with such a thorny discussion is difficult, because different parties may very well have different interests. But on top of that, it is also not always clear whether people (scientists, policymakers, and the broader public) understand or talk about concepts of justice in the same way. Not explaining scientific insights clearly enough creates confusion in the interpretation and use of results.

In a recent journal article, we proposed a justice framework synthesising different dimensions of justice into a framework that can be used by climate scientists and policymakers. Climate justice includes distributional, procedural, corrective, recognitional, and transitional justice.

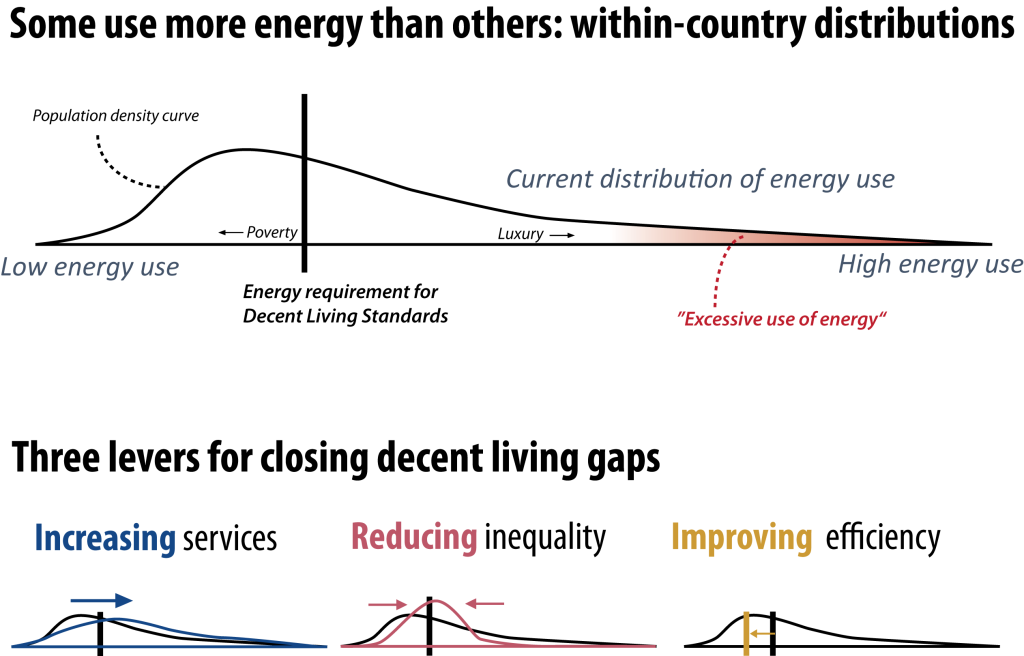

My PhD work focuses mostly on distributional justice. My PhD looks at where around the world decent living standards (i.e. the material prerequisites for human well-being) are met, and how much resources it would take to supply them to all.

Decent living standards, and particularly the minimum amount of energy required to be able to provide such living standards to all, are an important element of distributional justice within future climate scenarios. The transition to a net-zero economy comes with sweeping changes in the supply and use of energy, making the equitable distribution of clean and affordable energy crucial. There should be enough energy available for each person to live a decent life.

The first step is then to figure out how much energy is needed to fill decent living gaps around the world and sustain people’s energy needs. Luckily, the amount of energy necessary to provide a decent life for all does not put climate goals at risk. However, all of this is dependent on what actions will be taken by countries on climate and development.

The next step therefore is to connect these insights to models that capture the energy transition, simulating how energy efficiency of providing necessary services changes alongside changes in energy use patterns and inequality.

In order to end up in a sustainable world with decent living standards for all, some countries may see steep energy demand reductions, while others require strong increases in energy availability.

One approach is creating pathways that seek to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2030 and continue positive trends thereafter while also achieving the Paris climate goal during this century. This approach not only addresses the urgent need for climate action but also promotes a just and sustainable foundation for decent living standards across diverse populations.

While there may be a broad agreement about the overarching goal (a sustainable future), people disagree about the best way to get there. Multiple research teams are working on describing and quantifying possible interpretations of such sustainable development pathways.

Ideas range across focusing on innovation and technological solutions, to focusing on strong institutions and regulation, or focusing on sufficiency and local solutions in a post-growth economy.

Each future will have different challenges, but there may be ways for multiple futures to be consistent with pursuing the SDGs – even if they are radically different for an indicator like GDP/cap. Moreover, the community needs to have a big discussion about the differences in desirability and feasibility of such alternative development pathways.

Now is the time for a broad scientific effort to systematically explore the dimensions of justice I mentioned above – with many new tools that are being developed. Many hands are needed here, and the inclusion of many perspectives from all over the world is a must.

Models can support thinking, not replace it

Crucially, these models are not supposed to replace our thinking. Scientific insights and numbers produced by models are never without context. They are supposed to help our thinking and decision-making. But, at the same time, our thinking alone is often not good enough.

Especially when it comes to more conceptual debates such as around justice, people tend to (often unknowingly) have a different understanding of the same word. This creates the risk of drowning in misunderstandings. In some cases, having quantifiable targets can help us have discussions with more precision and clarity.

Quantitative tools, like the ones I work with and develop, can help carefully design and describe different multiple potentially just transitions, with a workable, agreed terminology to talk about them. The goal of science here can be to enable better political discussions based on what we really have in mind.