Understanding how materials used in nuclear environments react to extreme conditions is key to their safe use.

Meet Tamas Zagyva, Research Associate at the Department of Materials, Imperial College London. His research looks at how neutron shielding materials behave under radiation and heat, and he was recently named a finalist for the National Skills Academy for NuclearPostgraduate of the Year Award.

We asked Tamas a few questions about his journey – read on to find out more.

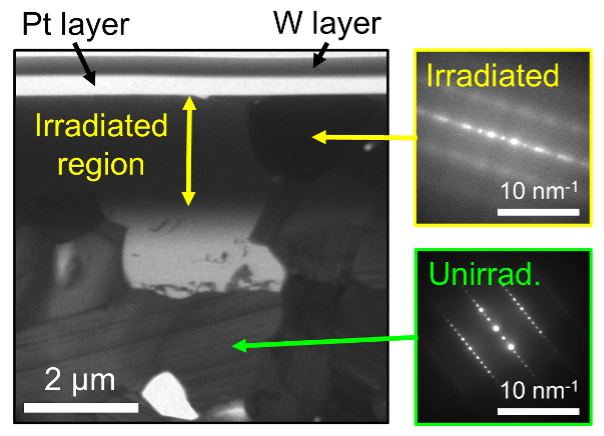

Cross-section of an ion-irradiated tungsten boride shielding material (bright-field transmission electron microscope image, left). The ion-damaged region is limited to the top ~2 µm of the surface. The corresponding diffraction patterns (right) indicate significant radiation-induced microstrain and displacement damage in the crystal structure.

- Can you tell us a bit about your background and what led you to pursue your postgraduate studies in Materials/Nuclear?

I did my undergraduate studies in Earth Science with a geology specialisation. I realised quite early on that mineralogy and crystallography were the fields I was most interested in, but I also found that I could learn much more about material structures and properties by continuing with a master’s degree in materials science. After that, I continued with a PhD focusing on radiation effects in nuclear waste materials, which felt like an obvious choice given the strong links to both geology and materials science. My PhD and postdoctoral research are quite similar, as both focus on understanding how materials behave under radiation.

- How would you describe your research in a few sentences for someone outside your field?

At Imperial, I study how the structure of neutron shielding materials changes under extreme conditions. These materials are used to protect radiation-sensitive components in nuclear reactors from neutron damage, but they also need to remain stable at high temperatures and under intense radiation. In our group, we simulate these conditions by bombarding materials with ions at different temperatures. The information we get from these experiments helps us choose the most promising shielding materials and improve them further.

- What’s the most exciting part of your work?

The most exciting part for me is analysing materials after irradiation experiments. Every material behaves differently, and often in unexpected ways. It’s fascinating that, using advanced techniques, we can observe how materials change at the atomic scale after radiation exposure.

- Have there been any unexpected findings or challenges along the way?

The biggest challenge is that ion irradiation only damages a very thin surface layer of the material. This damaged region is usually only about 1–2 micrometres thick, which is roughly 50 times thinner than a human hair. To analyse this layer, we need to handle the samples very carefully and use advanced sample-preparation and characterisation techniques, such as grazing-incidence X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy.

- Do you have any advice for other postgraduates aiming to make an impact in their field?

My main advice would be to work on something you’re genuinely passionate about. It makes a huge difference. I’d also encourage people to step outside their comfort zone. For me, that included approaching senior researchers at conferences, taking part in competitions, and getting involved in outreach activities. These experiences were challenging at times, but they were very rewarding and helped me move forward in my career.

- Who has been the biggest influence or mentor in your journey so far?

I’ve been lucky to be surrounded by many great mentors, so it’s hard to name just one. During my undergraduate studies in Hungary, I conducted research under the supervision of Gabriella B. Kiss, which I enjoyed so much that it significantly influenced my decision to pursue an academic career. I later wrote my undergraduate thesis under István Dódony’s supervision, who encouraged me to choose a topic I was genuinely interested in and further strengthened my passion for crystallography. During my master’s research, supervised by Katalin Balázsi and Csaba Balázsi on bioceramic materials, I enjoyed both the work and the research environment so much that I decided to continue in materials science.

- How did you feel when you found out you were selected as a finalist? What does this recognition mean to you personally and professionally?

Being a finalist feels great because it shows that the work I’ve done at Imperial over the past few years has made an impact and is being recognised by the industry. More importantly, it reflects how well our team works together under Sam Humphry-Baker’s supervision. Designing and coordinating ion irradiation experiments is complex, but doing this at a high level was only possible because of the support I received from Sam and the excellent work of the students involved in these campaigns.