The following is the response to cOAlition S request for feedback on Plan S and was written in consultation with academics, research committees and colleagues across the College.

BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY

Imperial College welcomes the move to align funder Open Access Policies. It also recognises that research and publication are global and collaborative ventures and that collaborators do not all have equal access to research funding, nor are most of them covered by funders with open access policies and aims.

At present it is estimated that cOAlition S signatory funded research results in the production of <8% global published outputs arising from research and that wholesale changes of business model are likely only once that funder base increases substantially. In the meantime, a mixed model will need to continue to exist.

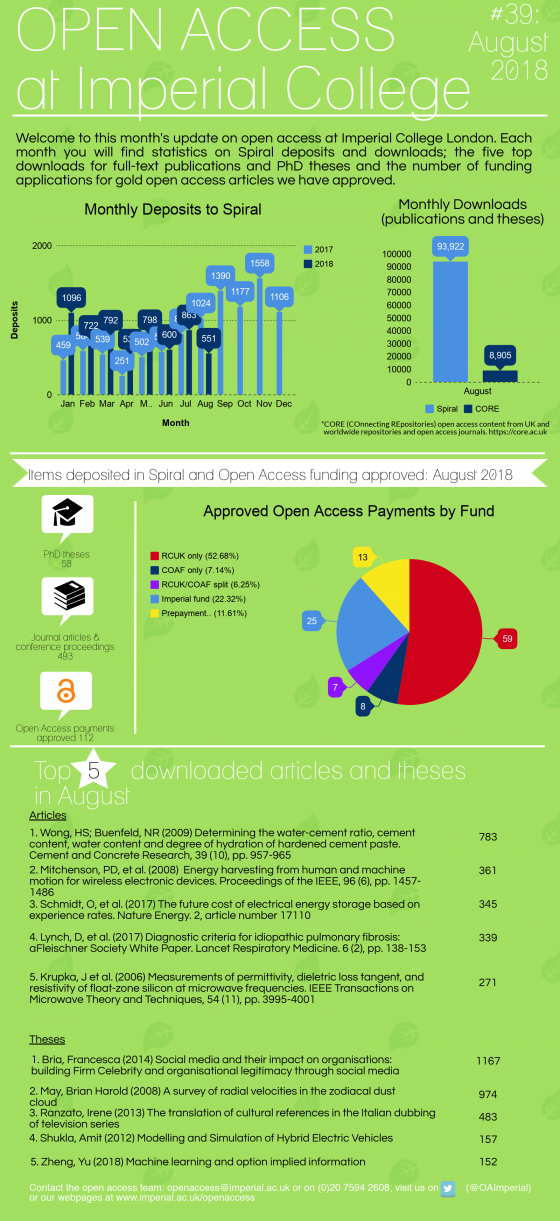

Nonetheless, Imperial College supports a general move to open access to the research findings of its academics – nearly 88% of 2018 College research outputs are available open access via a combination of full OA journals, hybrid journals, and repository deposit.

As they stand, the Implementation Guidelines present issues which may reverse this trend, result in an increased financial burden for research intensive institutions – at worst perpetuating the subscription model – and limit funding available for exploring new publishing business models, particularly models which would support learned societies. They also risk alienating a community already engaging in open science practices, some of whom have been at the vanguard of open access for over 20 years, including open access publishing. The suggestions below offer some responses to those issues, responses which were prepared following discussion at meetings of the Vice Provost’s Advisory Group for Research, at Faculty Research Committees and with individual academics.

Feedback summary

This Feedback is both aimed at eliciting clarification and at suggesting further actions that can be considered by cOAlition S funders which would, we believe, lead to the opportunity for practical, achievable and affordable steps to be taken towards accelerating Plan S aims of making full and immediate open access a reality. In summary, these include:

- Seeking an achievable implementation period, one which is scalable along with the growth in number of cOAlition S signatories and therefore the % global research outputs covered by those funders;

- Seeking clarification on the intentions around transformative publishing agreements and suggesting an approach that will not adversely impede choices of cOAlition S funded authors at a time when >90% of their counterparts may not be covered by such policies;

- Seeking clarification on the “unit” of the transformation agreements – Journal or Publisher? In making this response we stress that content is typically negotiated at publisher level, rarely at the level of the individual journal;

- Highlighting the role of a model Institutional Open Access Policy [1] as a mechanism for achieving Plan S aims, as a lever to constrain costs, as a mechanism to ensure retention of choice of venue of publication while membership of cOAlition S grows and while institution/consortial negotiations with publishers are ongoing;

- Seeking clarification of and changes to the repository deposit criteria to enable researchers to continue to harness the rich network of existing repositories available to them noting, in the UK at least, that we believe that no institutional repositories yet meet the Plan S repository criteria, that repositories are integrated with institutional current research information systems and that change in this systems infrastructure is highly unlikely to be considered until the conclusion of the 2021 Research Excellence Framework exercise.

- Noting effort needed to support learned societies in their re‐thinking of business models.

1. IS THERE ANYTHING UNCLEAR OR ARE THERE ANY ISSUES THAT HAVE NOT BEEN ADDRESSED BY THE GUIDANCE DOCUMENT?

Transformative agreements: By publisher or by journal?

It is essential that we seek clarification as to how Plan S interprets journals covered by transformative agreements [2] and that we analyse and communicate the consequences of that clarification. A discussion with one cOAlition S signatory raised alarm bells because they were talking about journals, not about publishers. In stating this position, they drew attention to Section 2 of the Guidance on the implementation of Plan S which includes the following two statements:

- Authors publish in a Plan S compliant Open Access journal

- Authors publish Open Access with a CC BY licence in a subscription journal that is covered by a transformative agreement that has a clear and time‐specified commitment to a full Open Access transition

To understand the implications of these guidelines, it is important to understand how content is licensed, how current and emerging transformative deals work and to recognise that universities, often as part of wider consortia, mostly subscribe to publishers (Big Deals) and not to individual journals. If Plan S really means journals then we anticipate considerable challenges, challenges which essentially set Plan S up to fail unless an exceptional set of circumstances come into alignment within the very short transition timeline indicated:

PUBLISHERS

- Libraries subscribe to bundles of content – typically via a publisher

- cOAlition S currently funds ~8% of global research outputs

- Read and Publish (R&P) deals are negotiated at the publisher level, not at the journal level, but they do ensure that over time, 100% of the outputs by academics at institutions taking the R&P Deal can be published OA in journals covered by that publisher R&P deal

- If all institutions covered by cOAlition S funders negotiate R&P deals with all publishers with whom their academics publish, then 100% of cOAlition S funded work published in journals published by those publishers is OA (i.e. whatever % of the ~8% global publishing that those publishers represent). However, not all journals will be OA under this scenario because some journals will attract few or no articles from cOAlition S funded research.

JOURNALS

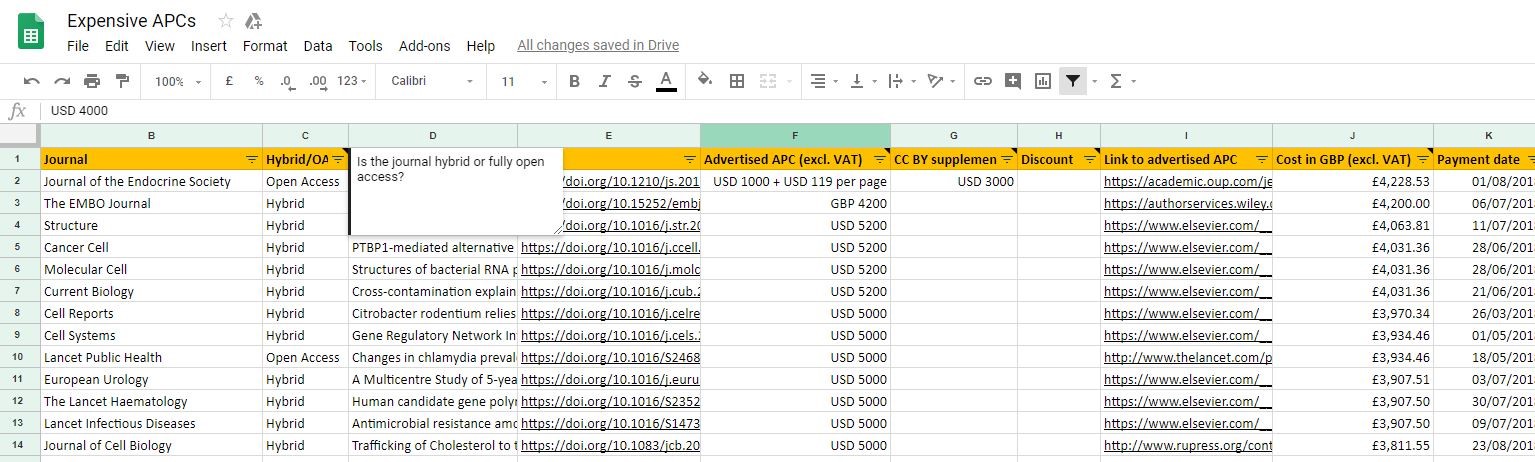

- For any given large publisher portfolio, the cohort of journals in which academics publish will change and evolve. Whilst an academic may still publish in a Publisher X journal, it may not always be the same Publisher X journal. Analysis of data from Imperial College shows that between 2012 and 2018 Imperial authors published 50,225 articles in 5,375 journals published by 762 publishers, of which 1,790 articles were single articles in 1,790 separate journals

- This gradual evolution of publishing choice, combined with the <8% funding coverage (cOAlition S funded research currently funds significantly less than 10% global published research outputs), create a challenge for publishers if cOAlition S are evaluating success at the journal level (as was understood from the cOAlition S funder discussion): the likelihood of a publisher flipping each journal in which an academic covered by cOAlition S funding publishes is very remote – certainly whilst the % publishing covered by those funders remains this low. The Imperial analysis shows that there is a very long tail of journals with single digit article publishing in any one year. For some journals, the publication rate is rising, for others, it is declining. The tail remains very long and includes many society journals where the society has outsourced its publishing activities to one of these commercial publishers. Unless the journal is only publishing cOAlition S funded work or is publishing a growing % cOAlition S funded research, it will almost certainly not be in position to flip to OA.

- If cOAlition S means *journal* rather than *publisher*, our reading is that unless all the following conditions are met, Plan S will fail:

- cOAlition S successfully bring on board all other significant funders of research

- All publishers of cOAlition S funded outputs are willing to offer an affordable R&P deal to all institutions covered by cOAlition S funders

- All institutions covered by cOAlition S funders take the deal.

If, however, we are talking about publishers, then under the publisher scenario above, it is possible for academics at cOAlition S funded institutions to meet Plan S aims where the deal is affordable to institutions, and scales to 100% of that institution’s publishing over time.

ADDITIONAL ATTRIBUTES OF A TRANSFORMATIVE AGREEMENT THAT MIGHT BE CONSIDERED BY PLAN S

- Machine readable licences to facilitate the flow of data and the automation of some text and data mining activities which can legitimately be performed on OA content.

- Where a publisher is not yet in a position to offer a transformative deal, or to flip their journals to Open Access, it offered either

- a Plan S compliant self‐archiving route, or

- an undertaking not to refuse to publish work from an author solely on the grounds that the author belongs to an institution which has adopted a Plan S compliant Institutional Open Access Policy whereby rights are retained on behalf of academics and Author Accepted Manuscripts can be self‐archived.

Timescale

To which entity (journal or publisher) any cOAlition S funder policy applies, and from which date are key factors in ensuring that Plan S aims are achievable. Publisher negotiations can sometimes take two or more years to reach a conclusion and negotiations are generally staggered so as to be manageable by institutions and consortia.

Learned Societies do not yet necessarily have alternative publishing service providers to turn to, and the length of time from a decision to consider a move of provider to first publishing with a new provider can be considerably in excess of three years with some contracts lasting up to seven years. We recommend that the guidelines recognise these timelines and that these will be directly influenced by the pace at which the cOAlition S group grows.

Open access repositories

As written, the guidance appears to require publishers to undertake/facilitate the work of repository deposit and the repository criteria appear to have been drawn up with this in mind. However, we envisage a scenario, particularly in the early years of Plan S implementation, whereby an Institutional Open Access Policy incorporating rights retention and Plan S compliant licensing and embargo periods will be needed in addition to publisher negotiations for transformative publisher deals, particularly in the event that those deals prove to be unaffordable. That being the case, author self‐archiving will most likely be the means by which Author Accepted Manuscripts will be deposited and made available through repositories. To this end, it would be helpful if the current repository infrastructure were also considered as a valid and valuable mechanism to meet Plan S aims.

With the above in mind, we support the COAR response [3] to the Plan S repository requirement statement.

To set this in context: at Imperial we have already experienced strong publisher pushback on proposals to roll out adoption of a model Institutional Open Access Policy in the UK – the UKSCL Model Institutional Open Access Policy – and as such, rather than contributing to the perpetuation of the status quo for subscribed content, it is our belief that widespread adoption of an Institutional Open Access Policy which meets Plan S requirements will provide a further legal lever to encourage publishers to develop their own affordable and transformative routes towards achieving Plan S aims and to demonstrate the value that they otherwise add to the scholarly communications process beyond the availability of the AAM text in a repository.

2. ARE THERE OTHER MECHANISMS OR REQUIREMENTS FUNDERS SHOULD CONSIDER TO FOSTER FULL AND IMMEDIATE OPEN ACCESS OF RESEARCH OUTPUTS?

The role of an institutional open access policy which retains rights which achieve Plan S aims

We believe that institutional open access policies have a role to play in meeting Plan S aims:

- As a lever to constrain costs. Widespread deals which result in a “read and publish” service for universities/consortia are a relatively new development and cost constraint, affordability, value for money and global applicability remain unproven. At their worst, they run the risk of perpetuating the subscription model and of tying funding up with traditional publishing rather than releasing it to support new initiatives. Universities may need an alternative means of ensuring the outputs of their researchers are available open access. An Institutional Open Access Policy which achieves the rights retention and availability envisioned by cOAlition S would fulfil this role, particularly if it enabled the release of funding to support alternative models of scholarly communication of research findings, e.g. a Diamond Open Access model which relies on core funding for the infrastructure and where no APC is paid by contributing academics.

- cOAlition S support for an institutional rights‐retention policy [4] as a means of advancing cOAlition S funder aims would allay significant concerns amongst the research community that publishing choices may become overly restricted by circumstances beyond their control.

The role of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment – DORA – in scholarly communications culture change

Imperial is a signatory to DORA and is currently working through implementation.

There are a growing number of institutions signing DORA and moving to implement it. That number remains relatively small and academics at signatory institutions are conflicted in some of their dealings with collaborators and collaborating institutions. Continued funder assurances that the quality of the individual output and not the quality of the vehicle of publication will be assessed in grant funding applications is necessary in order to embed what is likely to remain a slow pace of change globally. We would welcome moves by the cOAlition S group to be more explicit in explaining how they will enact their commitment to reform of research evaluation, including how they will recruit international partners.

Global research and learned society publishing

- As with commercial publishers, the business models for Learned Society publishing vary widely, from operating at a loss, to operating at very significant margins which at the extreme exceed those of the commercial publishers in % terms. Nonetheless, the following comments are relevant to this type of publishing.

- Academics are members of learned societies many of which have outsourced their publishing activities to commercial publishers

- Academic research is collaborative and global. The most appropriate venue for publication may not necessarily operate in a cOAlition S region, nor may the majority of the researchers/authors necessarily be in receipt of cOAlition S funding.

- Typically, it can easily take three years for a learned society to move from one publisher service to another, and typically, a learned society is receiving and reviewing content now that will not be published for approx. 2 years (2021).

- Viable alternative publishing service providers which support Plan S aims are not yet readily available in all disciplines and may need support at the discipline level from cOAlition S funders.

- Many learned societies publish a significant proportion of research which is not covered by cOAlition S funding. To prevent cOAlition S funded researchers from publishing in these journals would create an artificial barrier to research communication

- In a global context, institutions covered by cOAlition S research funding are at the wealthier end of the university market. Meanwhile, many learned societies actively encourage global collaboration irrespective of means. A world in which those less able to pay found themselves moving from paying to read to paying to publish would not be a world which has resolved inequalities of access to scholarship and sharing.

- Academics are aware that current OA funding, even where it only supports publication in journals listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), or hybrid – either where a viable self‐archiving option is not available, or where a ‘read and publish’ deal via hybrid funding is available – is no longer sufficient to support publishing at that institution, let alone to support the emergence of new business models which would support society publishing.

Financial challenges for research-intensive institutions

Imperial is a research‐intensive institution. We have calculated that using the current average APC prices paid, paying to publish would cost over double our current subscriptions budget and would add circa £10m to current content costs. Even were it the case that across the UK the funding in the system was sufficient to support OA publishing of research, that funding is not currently allocated where it is needed to support a move to OA.

Why libraries can’t simply cease subscribing and use savings to fund OA

This observation is a response to several comments that cOAlition S funders have made regarding their assumptions on what library subscriptions currently fund.

With many publisher “big deals”, libraries have a mixture of “subscribed content” – usually a subset of the portfolio of journal titles covered by the deals – and additional content in the journal portfolio which is also accessible to academics at the institution. Publishers typically allow a small % shift of subscribed titles annually, usually based on value. Some institutions have kept a keen eye on their subscribed content to ensure that it matches use (e.g. reading‐list material and highly‐used journals). Others have not been so diligent and because publishers only allow this small % shift of subscribed titles annually it is not possible in any one year for those institutions to undertake retrospective sweep to ensure that all the content to which an institution continues to subscribe is the content that is most used by those at the institution. This is important because, generally speaking, whilst an institution may have a Post Cancellation Access – PCA – agreement that generally only covers subscribed content and not to everything else that the institution has been accessing/reading in the portfolio outside the subscribed content.

Because most institutions no longer subscribe to print copies, they are reliant on post-cancellation access to subscribed journals. PCA gives this access to those journals. If libraries have not kept a keen eye on subscribed content and adjusted over the years, the big risk is that in a scenario in which a library needs to cancel licensed access, unless they have PCA to the content that has been historically used by their institutions their users will lose access to those journals. Subscribed title records partly lie with institutions, partly with publishers and partly with subscription agents. Libraries may have changed agent a few times since taking out the original subscriptions (these date back to the mid‐1990s), and a number of agents have folded during this period, jeopardising access to accurate information. What we do know is that across the board, institutions do not collectively have PCA access to all the content that their researchers use – the tail is very long indeed.

In the UK, Jisc is seeking to resolve this with each new negotiation but not all publishers are willing to engage in such discussions.

None of the above is a caused by, nor can be solved by OA / Pay to publish. However, it is a very significant factor when considering cancelling subscriptions in favour of supporting OA and to switching to Inter Library Loan (ILL)/Document Delivery for content not covered by PCA. If institutional usage of content does not closely match subscribed content, then the institutional ILL bill outstrips what was previously paid for the cost of licensed access to content before diverting unspent library subscription funds to support “pay to publish” can be considered.

ARE THERE ANY ISSUES AROUND THE FEASIBILITY OF PLAN S, E.G., KNOWN BARRIERS, AREAS WHERE THERE MAY NEED TO BE AN EXCEPTION?

The main barrier to the success of Plan S is the relatively low % content covered by cOAlition S funders. For Plan S aims to become reality, significant effort needs to be devoted to expanding the list of signatories to cOAlition S, or to other groupings seeking similar aims to Plan S. To this end, we see the recent announcement that librarians and funders in China are seeking immediate access to funded research outputs as a significant move, but unless there are similar moves with US funders the tipping point will be hard to reach.

Prepared on behalf of Imperial College London by Chris Banks

chris.banks@imperial.ac.uk

@ChrisBanks

[1] The response from the UKSCL Community outlines this in detail

[2] Typically, these are deals negotiated at a publisher level. They are becoming known as “Read and publish” deals and over time they allow read access to all content from that publisher covered by the deal and allow an institution’s academics to publish open access in all journals covered by the deal.

[3] COAR’s Feedback on the Guidance on Implementation of Plan S

[4] E.g. the UKSCL

Read Response to Guidance on the Implementation of Plan S from Imperial College London in full