Name: Connor Wright

Position: PhD Student in the Department of Materials

Research Group: Professor Mary Ryan

Research Focus: Connor is part of the newly founded InFUSE Prosperity Partnership, linking Imperial research with state-of-the-art techniques to progress the energy transition. His research focuses on the degradation of Sodium-ion batteries, widely considered the next big thing in battery energy storage.

What inspired you to study for a PhD?

Before university, I didn’t even know that ‘Materials Engineering’ was a thing. As anyone interested in the sciences at school does, I thought my options were limited to medicine, the natural sciences or the more classical engineering routes (civil, mechanical, electrical, etc.). It was only a couple of weeks before the UCAS deadline that I discovered – thanks to my sixth form tutor (thanks again, Mr Hunt!) – the wonders of Materials Engineering.

I applied for and got accepted onto the course at the University of Birmingham and have never looked back. The top-down approach, where you start with an application, assess the materials requirements, and then go to work on manipulating materials at the most fundamental level to achieve these, was something that really resonated with me. In my third year I chose a battery-related group project, thinking they were a worthy application to focus on with this top-down approach. In my Masters’ year, I again chose batteries for my individual project, focusing more on recycling. Continuing onto a PhD was the logical next step. I love the research culture, and where better to go than Imperial!

Can you tell us more about your research?

I focus on cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries (NIBs). Like lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) that we all have in our mobile phones, NIBs work by shuttling and storing positively charged ions and atoms, respectively, between two electrodes. The key difference is that NIBs use sodium, which is cheaper and more sustainable than lithium but heavier and less energy-dense. These properties make NIBs suitable for large-scale energy storage solutions and very suitable for renewable energy conversion like wind and solar. While current grid-scale storage relies heavily on pumped hydro, its cost and geographical constraints limit its global application. NIBs could be the bridge to a fully decarbonised society.

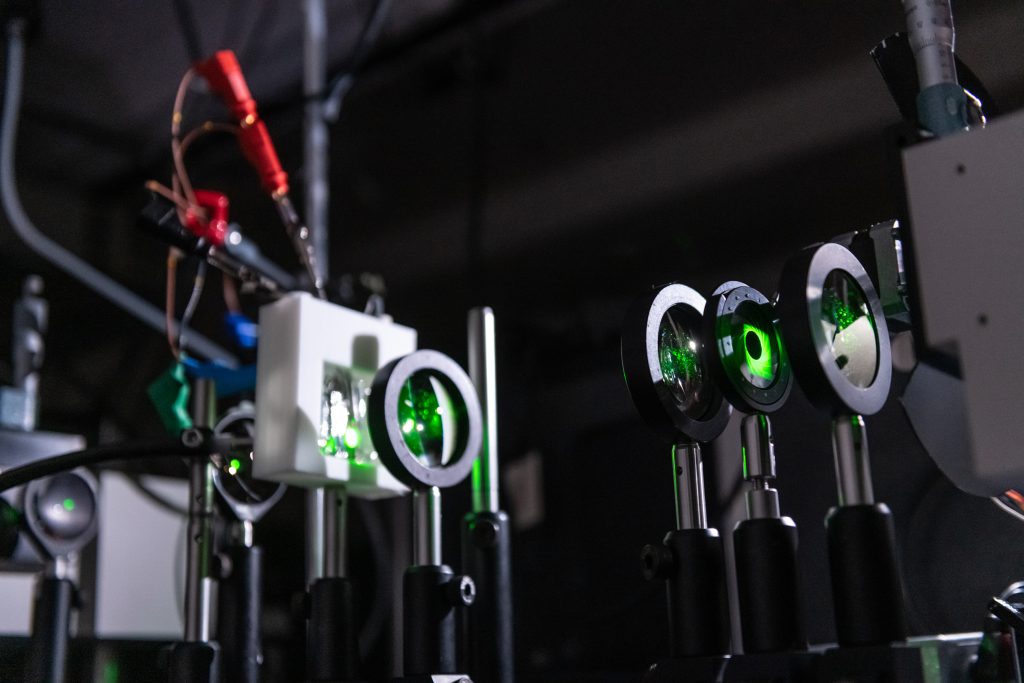

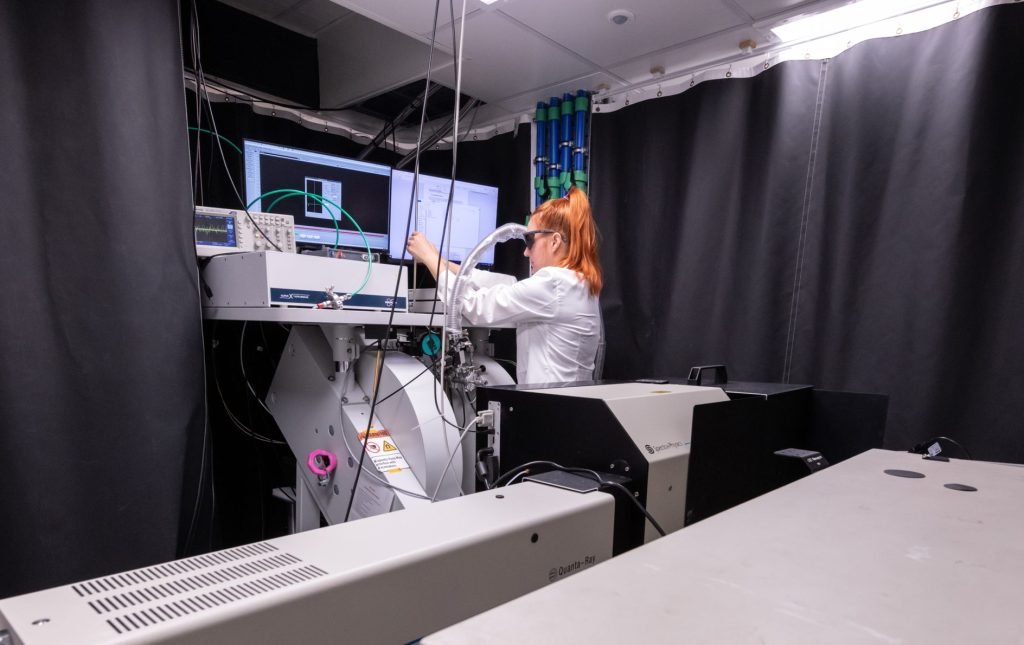

My work aims to understand why some promising NIB materials degrade as fast as they do. I engineer methods to study these materials at the smallest scale and in real-time, as they charge and discharge. These specific techniques are labelled ‘operando’.

At the UK’s national synchrotron facility, I conduct experiments that involve firing high-energy X-rays into my batteries to gather all sorts of useful (and awesome) information. One key technique, X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS), provides insights into the chemical and electronic structure of the host electrode material. Looking for unusual changes in the XAS signal as my target electrode charges/discharges is a large part of what I do as a researcher.

What does a typical day involve?

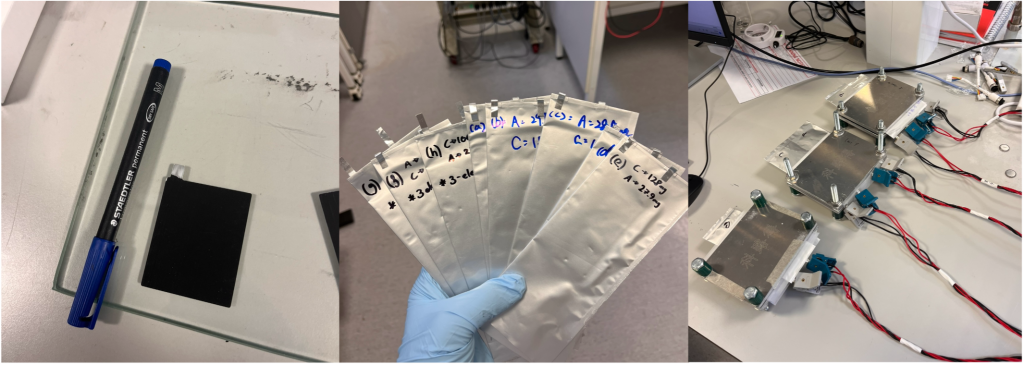

A typical day would see me in the lab making and testing batteries. Production is a complicated and multi-step process, so depending on which stage I’m at, this could mean using furnaces, slurry mixers, coating machines, or the testing/cycling rig. Most days will also involve some sort of data analysis, either cycling data from the lab or some more hardcore stuff from a recent synchrotron experiment. However, as with all research, no day is ever the same, and things are always changing!

Can you tell us more about your research group?

I work in two different groups, which is not uncommon here at Imperial. My primary supervisor is Prof. Mary Ryan in Materials, but most of my lab work is with Prof. Magda Titirici’s Battery team in Chemical Engineering. In my second year, I organised Mary’s biweekly group meetings and also went to both France and China with Magda’s group for conferences.

What do you enjoy outside of your PhD?

I wouldn’t be where I am today if it weren’t for sport. I’ve played field hockey my whole life, and throughout the PhD is no exception. I also love music and regularly attend a ‘pub choir’ in south London with many friends. Coming from a farm in rural Leicestershire, I also need my regular dose of fresh air and greenery, so I often take hikes out of London with my girlfriend.

Slightly closer to home, I enjoy my work as an Outreach Ambassador for the Department of Materials. As I said at the start, not many people know about Materials as a field, let alone a degree or career option, and that’s a real shame! I’ve done lab demos at Imperial’s Open Days, helped run stands at public events such as The Great Exhibition Road Festival and even organised my own event for 2023’s Pint of Science Festival.

Dr Jerry Sha is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Stephen Skinner. He joined the Department as an undergraduate student in September 2013.

Dr Jerry Sha is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Stephen Skinner. He joined the Department as an undergraduate student in September 2013. Dr Anna Winiwater is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Ifan Stephens. She joined the Department of Materials this year.

Dr Anna Winiwater is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Ifan Stephens. She joined the Department of Materials this year. Dr Pankaj Sharma is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Fang Xie. He joined the Department of Materials this year.

Dr Pankaj Sharma is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Fang Xie. He joined the Department of Materials this year. Dr Megan Owen is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Sir Robin Grimes. She joined the Department of Materials in 2022.

Dr Megan Owen is a Research Associate in the group of Professor Sir Robin Grimes. She joined the Department of Materials in 2022. Dr Apostolos Panagiotopoulos is a Research Assistant in the group of Professor John Kilner. He joined the Department of Materials in 2018 as a Research Postgraduate.

Dr Apostolos Panagiotopoulos is a Research Assistant in the group of Professor John Kilner. He joined the Department of Materials in 2018 as a Research Postgraduate.

My research group (the metals electrochemistry group, led by Dr Stella Pedrazzini) is undoubtedly one of the reasons I enjoy doing my PhD so much. We meet once a week to update each other on what we have been up to, whether it is a failed experiment, writing research proposals, or going on holiday!

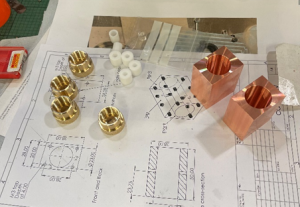

My research group (the metals electrochemistry group, led by Dr Stella Pedrazzini) is undoubtedly one of the reasons I enjoy doing my PhD so much. We meet once a week to update each other on what we have been up to, whether it is a failed experiment, writing research proposals, or going on holiday! Mike: Workshops are important to produce of a wide range of goods. When you think about it, everything around you is likely created in a type of workshop, from transport to household items and clothing – it just depends on the size, scale, and capability of the facility. In the Department of Materials, we focus on making components that can support research or teaching – and we are always up for a new challenge!

Mike: Workshops are important to produce of a wide range of goods. When you think about it, everything around you is likely created in a type of workshop, from transport to household items and clothing – it just depends on the size, scale, and capability of the facility. In the Department of Materials, we focus on making components that can support research or teaching – and we are always up for a new challenge! Most parts machined in the workshop are made from metal or plastic. In recent years, we have witnessed a growing demand for the use of new materials such as Peek. Peek is a fairly new material. It has become an increasingly popular material, replacing PTFE for sample holders, as it doesn’t contaminate the material which is being tested, is a more stable material from a machining perspective and is able to operate at higher temperatures.

Most parts machined in the workshop are made from metal or plastic. In recent years, we have witnessed a growing demand for the use of new materials such as Peek. Peek is a fairly new material. It has become an increasingly popular material, replacing PTFE for sample holders, as it doesn’t contaminate the material which is being tested, is a more stable material from a machining perspective and is able to operate at higher temperatures. What do the team most enjoy about their roles in the workshop?

What do the team most enjoy about their roles in the workshop?

The newly discovered method at AlixLabs allows ALE to be selectively performed on inclined surfaces – which in turn can be fabricated by epitaxial growth and dry etching. Our task was to get an approximate of how GaP (Gallium Phosphide) will be etched if chlorine (Cl) was used as the plasma and obtain the values of surface energy required for it. To achieve this, we used the Espresso and Jaguar software provided through Schrödinger, which allowed us to build a GaP crystal and turn it into a slab having some amount of vacuum space. Upon adding a Cl

The newly discovered method at AlixLabs allows ALE to be selectively performed on inclined surfaces – which in turn can be fabricated by epitaxial growth and dry etching. Our task was to get an approximate of how GaP (Gallium Phosphide) will be etched if chlorine (Cl) was used as the plasma and obtain the values of surface energy required for it. To achieve this, we used the Espresso and Jaguar software provided through Schrödinger, which allowed us to build a GaP crystal and turn it into a slab having some amount of vacuum space. Upon adding a Cl All in all, we really enjoyed the experience of being able to contribute our part and have this opportunity to travel to Sweden and learn more about AlixLabs and semiconductors. This has certainly deepened our knowledge in this research area, and we are very grateful to continue our alliance with them.

All in all, we really enjoyed the experience of being able to contribute our part and have this opportunity to travel to Sweden and learn more about AlixLabs and semiconductors. This has certainly deepened our knowledge in this research area, and we are very grateful to continue our alliance with them.

I work on the environmental degradation of engineering alloys. I look into the oxidation and hot corrosion of nickel and cobalt based superalloys and aqueous corrosion of steel. To this day, very few research groups around the world work on corrosion due to the challenges involved in this type of investigation. My research group also consists of mostly women – which is very unique in STEM. I also teach the 1st year undergraduate module in Materials Electrochemistry.

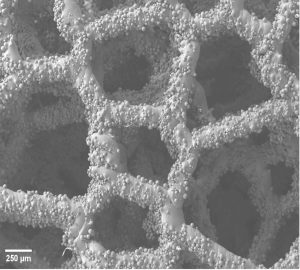

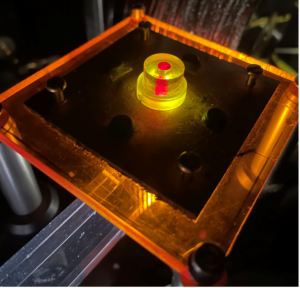

I work on the environmental degradation of engineering alloys. I look into the oxidation and hot corrosion of nickel and cobalt based superalloys and aqueous corrosion of steel. To this day, very few research groups around the world work on corrosion due to the challenges involved in this type of investigation. My research group also consists of mostly women – which is very unique in STEM. I also teach the 1st year undergraduate module in Materials Electrochemistry. Light contains so much information about all the materials in nature. The more in-depth we analyse all the shades of light interacting with matter, the richer details are revealed and nanotechnology helps boost light-matter interactions. I utilise nanotechnology to develop smart sensing platforms boosting these light-matter interactions to detect disease biomarkers. We expect that the sensing platform would allow for fast screening of diseases, and therefore the early detection and treatment of diseases in the future.

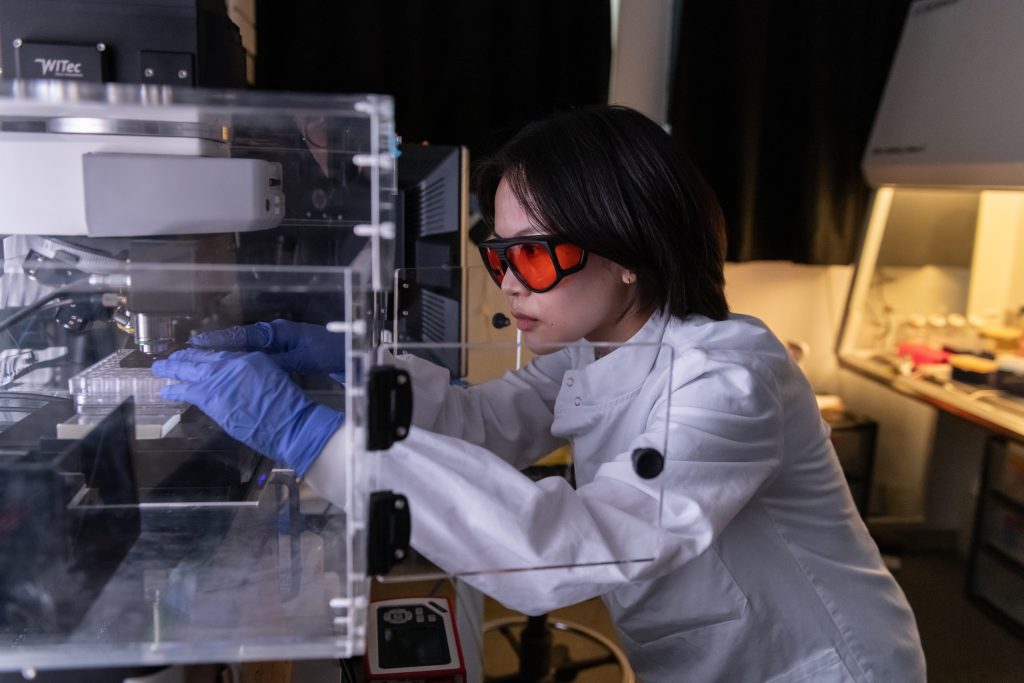

Light contains so much information about all the materials in nature. The more in-depth we analyse all the shades of light interacting with matter, the richer details are revealed and nanotechnology helps boost light-matter interactions. I utilise nanotechnology to develop smart sensing platforms boosting these light-matter interactions to detect disease biomarkers. We expect that the sensing platform would allow for fast screening of diseases, and therefore the early detection and treatment of diseases in the future.

I am the facility manager for the

I am the facility manager for the

I work on discovering active, stable and low-cost materials that can catalyse green hydrogen production from water using renewable electricity.

I work on discovering active, stable and low-cost materials that can catalyse green hydrogen production from water using renewable electricity.