For World Water Week, Dr Anna Phillips from the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative explains clean water is crucial to the elimination of schistosomiasis.

Can you imagine life without access to clean water? Unfortunately for 663 million people this is a reality. That’s nearly one in ten people worldwide living without a safe water supply close to home, spending hours queuing or trekking to distant sources and coping with the health impacts of using contaminated water. SIWI’s (Stockholm International Water Institute) World Water Week, is a pertinent time to reflect on important research carried out by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI), a non-profit initiative based at Imperial College London, which highlights why access to clean water is so important to human health.

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a type of parasitic ‘worm’ infection affecting individuals in sub-tropical and tropical regions of the world. It is a major, yet neglected public health problem, where estimates showed that at least 218 million people required preventive treatment in 2015, of which at least 20 million suffer from severe and debilitating forms of the disease (World Health Organisation, 2016). The SCI support treatment programmes against schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth infections in 16 sub-Saharan African countries and Yemen. Since its foundation in 2002, the SCI has supported the delivery of over 140 million treatments for these infections.

Schistosomiasis transmission occurs when people suffering from the disease contaminate freshwater sources with their urine or faeces, containing parasite eggs, which hatch in water. Individuals become infected when larval forms of the parasite – released by freshwater snails – penetrate the skin during contact whilst swimming, fishing, washing clothes, or bathing in infested water.

The lifecycle of schistosomiasis, Natural History Museum

Schistosomiasis can often result in abdominal pain, diarrhoea and anaemia through loss of blood in urine or stool. It can also cause stunted growth and impaired cognitive development in children, and in turn, leads to reduced school attendance. Over time, adults can develop bladder cancer and women may be at increased risk of becoming infected with HIV. Due to this, adults may be left unable to work, ultimately trapping families in a cycle of poverty.

Schistosomiasis is particularly common in poor and rural communities without access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation. Even though water is crucial to the control of Schistosomiasis, it is not often the feature of large scale interventions. The World Health Organisation’s recommended control strategy is large-scale preventive chemotherapy (PC), whereby regular treatment is offered to all individuals in a geographical area depending on their determined level of disease risk (WHO, 2006). Studies have shown that treating schistosomiasis can increase school attendance by up to 25%, increase future earnings by 40%, and reverse damaging effects of infections.

How do we decide who is treated?

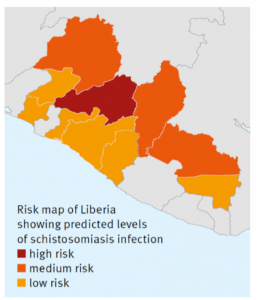

- Prior to treatment: SCI works with Ministries of Health in each country to assess the level

of infection, by taking and analysing stool samples from school-age children (5-14 years old) in randomly selected schools. SCI use the information gathered to develop risk maps, showing which areas require treatment and how often to distribute treatment.

of infection, by taking and analysing stool samples from school-age children (5-14 years old) in randomly selected schools. SCI use the information gathered to develop risk maps, showing which areas require treatment and how often to distribute treatment. - Treatment then begins: most programmes treat school-age children due to their higher disease burden and ease of distribution in schools.

- Monitoring and evaluation: levels of infection are assessed annually to ensure that treatment is effective and coverage of those receiving treatment is adequate. Costs are also monitored and cost-per-treatment determined. This all helps ensure that disease control programmes have a higher impact.

The limitation of school-based treatment is poor coverage among out-of-school children, particularly older children and those living far from schools, and not treating adults who are often also infected. The Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE) is a multi-country project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through a grant to the University of Georgia. SCORE’s aim is to understand the benefits and costs of alternative approaches to treatment for schistosomiasis control involving community wide treatment, school-based treatment and ‘drug holidays’ (i.e. years without PC). SCI was awarded three SCORE grants, one of which is in Mozambique and the other two in Niger, as part of its operational research to ensure the optimal strategy to control and ultimately eliminate schistosomiasis.

Between 2011 and 2016 the SCORE study collected samples from around 160,000 individuals in both Mozambique and Niger, with the aim of determining which treatment strategy provides the greatest reduction in schistosomiasis in school-aged children and adults. Information on potential environmental risk factors of local communities was also collected since water, sanitation and hygiene play a key role in preventing exposure and managing schistosomiasis, particularly with a future aim of elimination or eradication by 2020.

Access to clean water and sanitation facilities will be crucial to the elimination of schistosomiasis in the longer-term. SCI will continue to support treatment programmes to ensure that as many people as possible are free of schistosomiasis and are able to reach their full potential, whilst also strengthening collaboration with water and sanitation programmes.

For more information on the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative see: www.schisto.org and for information on the SCORE study see: https://score.uga.edu.

Dr Anna Phillips is a Senior Programme Manager for the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, based at Imperial College London.