Giskin Day makes the case for Imperial’s new Humanities, Philosophy and Law BSc – a pathway for medical students to combine the arts with medical science.

This year we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the NHS, but there is another birthday worthy of celebration. In 1948, the term ‘medical humanities’ was first used. George Sarton, who coined the phrase, believed that increasing specialisation in science and medicine failed to provide the framework for understanding the intellectual context and human significance of scientific developments. Medical schools around the world are increasingly coming to the same conclusion and incorporating humanities into medical education.

On hearing that I work at Imperial College London, I’m often asked, “What do you do there?” Most people express incredulity: “You teach medical humanities? I didn’t know Imperial did that sort of thing.” Happily, we do. We’ve recently merged two long-standing successful courses to produce our innovative new Humanities, Philosophy and Law BSc. It offers 25 places, divided between fourth-year Imperial medical students, intercalating students from other universities, and biomedical science students.

We’ve come to the end of our first year, and feedback is very encouraging:

‘I have had an incredible year and had my eyes opened to so many new and interesting things,’ wrote one student. ‘I have enjoyed the course so much, and I will value everything I’ve learned for years to come,’ said another.

Broad scope

Our course at Imperial, as well as being unique in its particular mix of disciplines, also stands out for the curated nature of the student experience. Most medical schools simply allow their intercalating students to join classes taught by other departments. Although students undoubtedly benefit from being in a class with those taking arts degrees, they can feel isolated. On our course, the class stays together and we tailor the content specifically for our students’ interests and needs. Many of our students become friends for life, but they also feel that this is a shared learning adventure – one in which they are protagonists rather than bystanders.

Particularly for those students who had found it tricky to give up humanities subjects at school in order to focus on science to get a place to study medicine, the course offers an opportunity to reengage with the humanities with a medical perspective. There can be no better city in the world to study the intersection of culture and medicine than London. Of course, there is the renowned Wellcome Collection of which we make good use, but there are dozens of other medical museums and exhibitions. At the beginning of the course students play a live, team version of ‘Medical Monopoly’, visiting as many venues as they can to answer site-specific questions and carry out ‘chance card’ challenges. Our course has a field trip every week. Highlights are medical aspects of the paintings in the National Gallery, a trip to the Museum of the Mind in Beckenham, and a visit to the Old Bailey to see court cases in action.

Multidisciplinary teaching

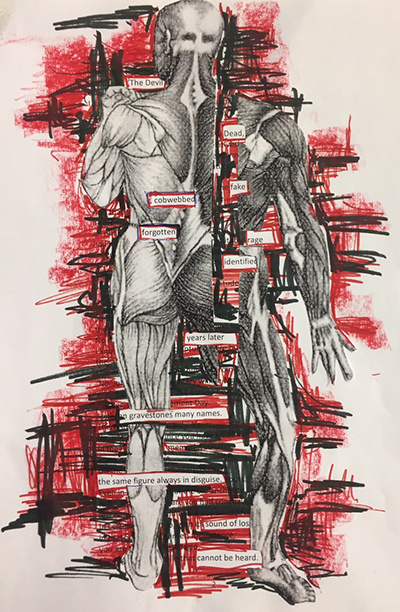

The course is divided into three themes: the body, the mind and death and dying. Each theme is explored through multiple lenses. If, say, we are looking at ‘dissection’, we will start with a history of dissection, including the nefarious art of body snatching. Then we look at the law relating to ownership of the body and the ethical issues this raises. Students can watch one of the course leads, pathologist Dr Michael Osborn, perform a post-mortem. We also explore dissection in literature: how it is often used as a rite of passage in accounts of medical acclimatisation. Then we do an arts workshop, where students literally ‘dissect’ a text, creating collages of words and images that capture new perspectives on the fragmented body.

There is a multidisciplinary team approach to teaching. Dr Wing May Kong leads on the ethics, and Greg Artus from Imperial’s Centre for Languages, Culture & Communication teaches philosophy. My specialisms are literature and the arts. We draw on a range of international experts to lead workshops. We have partnered with the Chelsea Physic Garden – one of the most inspiring spaces in London. Students designed tours and educational activities for the Garden as part of a formative assessment. The Garden memorably hosted a photography workshop led by patient-artist and activist Liz Atkin who explores psychodermatology in her work.

Reflective practice

All our students have the chance to create an artwork as part of their final project. Exploring the process of making, and the insights it affords, encourages reflective practice in ways that are creative and inspiring. For example, one student, Batya Stimler researched artists’ books made by breast cancer patients for her project. Making her own artist book was revelatory about the therapeutic nature of the process of creation, and also the importance of coming to terms with uncertainty:

“Analysing and interpreting artists’ books is full of uncertainty. There were many contradictory possible explanations. Getting used to being familiar and comfortable with uncertainty will hopefully prepare me for medicine where few things are black and white.”

Other projects explored such diverse issues as how children’s films depict parental loss, ‘fatness’ in art, the history of bread in war, zines in the LGBT+ community, mourning in the digital age, and the use of graphic novels to depict mental health issues.

I hope that the experiential learning we offer equips students with techniques to negotiate their own emotional boundaries in the demanding profession they have chosen to pursue. Although the course deals with some difficult issues, it is, at heart, a joyful celebration of the humanity at the heart of medical practice.

Giskin Day (@GiskinDay) is a Principal Teaching Fellow and a course lead for the intercalated BSc in Medical Sciences with Humanities, Philosophy and Law.

You can read more about George Sarton and the history behind medical humanities in this BMJ article.