For World No Tabaco Day 2017, researchers from Imperial’s Muscle Lab provide an insight into how smoking takes its toll on our lung health.

For World No Tabaco Day 2017, researchers from Imperial’s Muscle Lab provide an insight into how smoking takes its toll on our lung health.

Smoking is a leading cause of preventable death and disease in the world. It is estimated that the society costs associated with smoking are approximately ₤12.9 billion a year, including the NHS cost of treating smoking related diseases and loss of productivity.

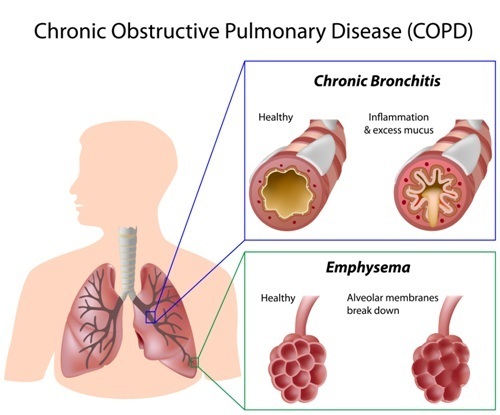

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the major diseases caused by smoking. The disease ranks third among the leading causes of death worldwide. Around 1.2 million Britons suffer from the disease (Source: British Lung Foundation). The usual clinical picture is that of a smoker with symptoms that include shortness of breath and chronic cough.

The muscle lab team at the Royal Brompton Hospital’s BRU, led by Professor Michael Polkey and Dr Nicholas Hopkinson is looking at different ways to improve COPD care, and at the different mechanisms by which interventions improve patient outcomes in the disease.

Wide-ranging consequences

In recent years, it has been discovered that the negative consequences of the pulmonary disease are not just limited to within the rib cage. The wider effects of the disease on multiple body systems has a large and solid evidence base to support it. More than half of COPD patients suffer simultaneously from at least two other conditions known to often occur alongside the disease (so-called ‘comorbid’ conditions); the presence of which is commonly used as an indication of disease severity (1). The disease burden usually takes its toll on the patients’ quality of life, daily physical activities and social interactions.

Limitation of daily physical activities (e.g. walking, gardening and cycling) remains one of the main problems facing COPD patients and has been shown to be a significant predictor of death (2). Research has shown that this is not just a result of the lung tissue destruction, but also a consequence of the associated skeletal muscle dysfunction. The systemic inflammation found to be associated with the disease, leads to a decrease in muscle mass (3). It was also found that there are microscopic changes in the nature of the muscle fibers, towards a less enduring type with smaller size and lower capillary density (4). This not only means worsening of the inherent  muscle properties (power and endurance) but also less available oxygen for aerobic energy production. The result is a lower capacity for exercise, not only due to chest problems, but also because of muscle ‘atrophy’. The process unfortunately, if undealt with, takes a downward spiral, with the lack of adequate exercise causing muscle de-conditioning. This means that muscles, owing to their disuse – by varying degrees, start to atrophy, further aggravating the problem.

muscle properties (power and endurance) but also less available oxygen for aerobic energy production. The result is a lower capacity for exercise, not only due to chest problems, but also because of muscle ‘atrophy’. The process unfortunately, if undealt with, takes a downward spiral, with the lack of adequate exercise causing muscle de-conditioning. This means that muscles, owing to their disuse – by varying degrees, start to atrophy, further aggravating the problem.

Pulmonary rehabilitation, an exercise and educational program for chronic lung conditions, is a main treatment option in COPD patients. It has been shown in numerous studies to be one of the most valuable interventions in this disease, mainly by improving the muscle dysfunction caused by the exercise limitation. Other treatments for COPD include inhalers containing anti-inflammatory drugs and bronchodilators that target the inflamed narrowed airways. However, it is imperative to tackle the main cause of the problem to optimize patients’ conditions. Giving up smoking is considered to be the most important treatment, with health effects that go well beyond the respiratory system’s airways and lungs. Needless to say, quitting is associated with many health benefits in the short- and long-term, the most important of which is a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. However, despite the large body of evidence on the merits of smoking cessation, its effect on muscle mass and function has not been adequately studied in COPD patients.

Adding life to years

We are currently conducting a study with the aim of identifying the effects of smoking on the atrophied muscles in COPD patients , alongside testing smokers without COPD as controls. All participants in the study join a smoking cessation program for at least 6 weeks during which they receive counseling, information about the different aids to quit in addition to nicotine replacement therapy or prescription drugs. At baseline, measurements of their lung function parameters, exercise capacity and exhaled carbon monoxide levels are made. Also, muscle power and endurance are measured using specialized equipment to gauge voluntary and involuntary strength components. After 3 months of quitting smoking, the same measures are repeated. Quantifying the changes in muscle properties and lung function following smoking cessation allows a better understanding of the factors affecting exercise capacity. This serves to highlight the importance of such a high value intervention in smokers and COPD patients for not just adding years to life, but more importantly adding life to years.

You can find out more about this research on the NHLI website.

By Dr Ahmad Sadaka (Honorary Clinical Research Fellow, Royal Brompton Hospital) and Dr Faisal (ERS Postdoctoral Research Fellow, NHLI).

References

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet; 380:37-43

- Waschki B, Kirsten A, Holz O, et al. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest 2011; 140:331-342

- ATS/ERS. Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Statement of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 159:S2-40

- Hopkinson NS, Nickol AH, Payne J, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme genotype and strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170:395-399