For World Osteoporosis Day, Dr Victoria Leitch provides an insight into how her research in osteoporosis is working towards new treatments for this common condition.

As a young girl I spent many long afternoons in piano lessons.

Years later, I remember very little from the lessons – but I do vividly remember the teacher. She was very strict, had hair like candy floss and a severe hunch. She always made the lessons run long, but she would give me a chocolate bar if I helped her hang out her washing afterwards. She needed my help because she couldn’t reach the washing line anymore. One day I asked my mum why she had a hunched back and she told me it was because she had osteoporosis. At the time I didn’t really comprehend what that meant, but I knew it wasn’t good. One day she fell and broke her hip, and sadly, not long after that she passed away. As you read my story, I am sure it sounds familiar to a lot of you. Maybe not with a piano teacher, but with a relative, family friend or neighbour. The reason I say that is due to the rising prevalence of osteoporosis – one in three women and one in five men over the age of 50 are affected.

So, what is osteoporosis?

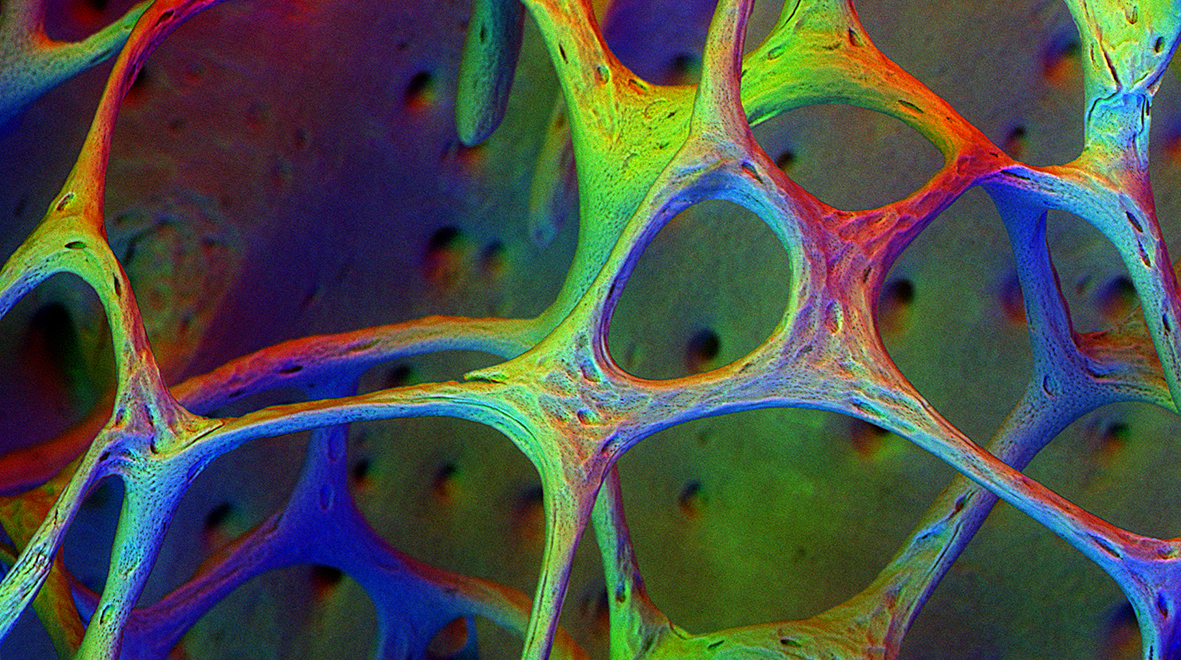

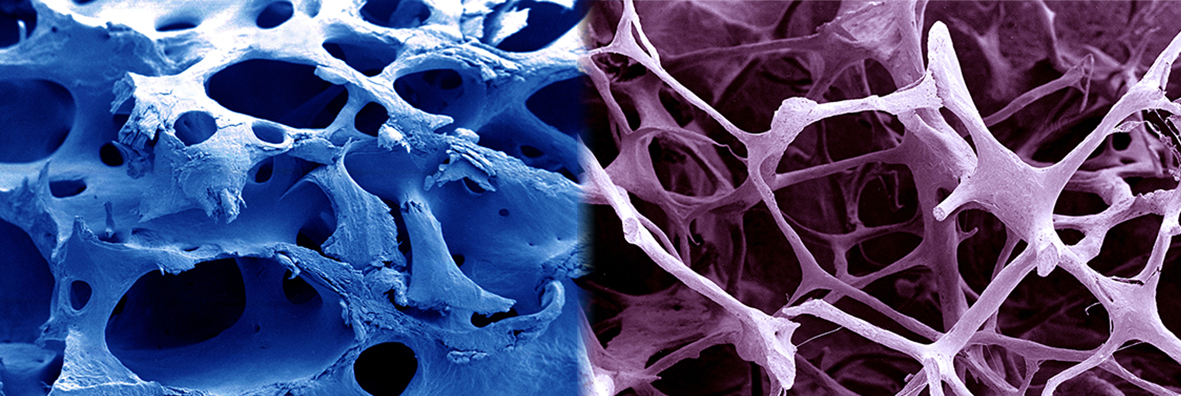

Osteoporosis is a disease in which the strength and quality of our bones decrease. Our bones are constantly changing, cycling through a process of remodelling where older bone is replaced with newly formed bone. This process involves a precise balance between the degradation of old bone and formation of new bone. In osteoporosis, this process is out of balance with more bone removed than formed. The trabeculae – the lattice-like structure inside the bone – becomes thinner and less in number, resulting in weaker bones.

A scanning electron micrograph image of normal bone vs old osteoporotic bone (computer colour-enhanced). CC BY 4.0

Not everyone is affected in the same highly visible way as my piano teacher. The disease can be silent, with many people unaware of the loss in bone density, until they experience a fracture. Osteoporotic fractures are life changing and may be life-threatening, with almost a quarter of patients dying within a year of an osteoporotic fracture. There are drugs available which can prevent bone loss, but these are not always effective, may be expensive and are associated with a number of side-effects, as highlighted recently in a commentary piece in Nature (While the process of bone turnover is relatively well-understood, the mechanisms that result in the imbalance of this process in osteoporosis are less so. What is clear though, is that an individual’s risk of osteoporosis risk is often inherited. So the answers to our osteoporosis questions, like with many diseases, may be hidden in our genes.

The Origins of Bone and Cartilage Disease

That’s where we come in! The Molecular Endocrinology lab at Hammersmith Campus hosts the Origins of Bone and Cartilage Disease (OBCD) team. The OBCD project started in 2014 thanks to a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award. Our work is based on the knowledge that the risk of bone and joint diseases is often inherited, but currently only 10% of this risk can be attributed to known disease-causing genes. Working in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium we are discovering new genes involved in bone disease by analysing a series of knockout mice each lacking one of the 20,000 protein-coding genes.

Our high-throughput screening platform lets us test the size, structure, and strength of bones from these knockout models. This gives us a quick and accurate way to identify new genetic targets for bone diseases like osteoporosis. You can track our progress on our website, where we publish all of our results in real-time.

The largest ever osteoporosis genome-wide association study (GWAS)

The ultimate goal is to turn the findings of our research into benefits for people with osteoporosis. The knockout mice, with skeletal abnormalities identified by our pipeline, represent potential animal models for drug discovery in the prevention and treatment of human skeletal disease. The importance and relevance of our research and our extensive international collaboration was recently highlighted by the publication of the largest ever osteoporosis GWAS in Nature Genetics which tripled the number of genes associated with osteoporosis!

One of the key new osteoporosis genes identified by this study was Gpc6. Mice lacking the Gpc6 gene were identified in our OBCD pipeline as having a major skeletal phenotype, with increased bone thickness, mineral content and strength. We now have the opportunity to use this model to determine the role that Gpc6 plays in bone. The exciting news is that Gpc6 is just one of many of the genes we are currently identifying. We hope that in the coming years, our work will lead to new treatments for osteoporosis, and the story about my piano teacher will become a thing of the past.

Dr Victoria Leitch is a post-doctoral research associate in the Molecular Endocrinology laboratory at the Hammersmith Campus of Imperial’s Department of Medicine. She works on the Origins of Bone and Cartilage Disease Project, which is funded by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award.

If you want to stay in touch with the OBCD team, you can find us on Facebook and Twitter, or on our website.

Following the launch of the Faculty of Medicine’s reorganised academic structure on 1 August 2019, this post was recategorised to Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction.

wonderful described article, useful information.

wonderful described article, i am always getting less knowledge about osteoporosis but after reading this i feel like i deeply understood it, thank you for this huge knowledge.