For Diabetes Awareness Week, Anna Cherta-Murillo explains how mycoprotein, a food made of fungus, may hold the promise for managing blood sugar levels in Type 2 Diabetes.

For Diabetes Awareness Week, Anna Cherta-Murillo explains how mycoprotein, a food made of fungus, may hold the promise for managing blood sugar levels in Type 2 Diabetes.

If I were to ask you the first thing that comes to mind when you think of fungi, you would probably say mouldy walls, gone-off food, or athlete’s foot. The Fungi kingdom is often not viewed in a positive light. However, we owe a lot to fungi; they produce life-saving antibiotics, have allowed organ transplantations in humans and can recycle many types of waste. In the area of nutrition, some fungi also have the potential to affect human health in a beneficial way, although little research has been devoted to it compared to other foods. In the Nutrition Section of the Department of Medicine at Imperial, we are putting fungi into the limelight and studying the impact of a particular type of fungus on blood sugar levels and appetite in South Asian and European people with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D).

The problem

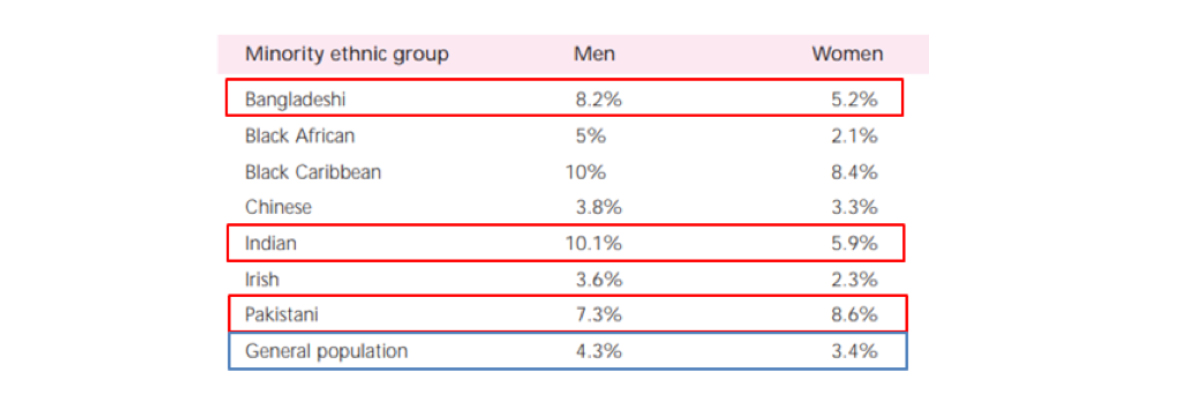

1 out of 20 people worldwide has T2D, with South Asians being more prone to the disease compared to Europeans (Figure 1). People with T2D have higher blood sugar levels than normal, which over time can increase the chances of developing long-term complications such as blindness, kidney disease and heart failure. It is therefore important to manage blood sugar levels in people with T2D in order to keep blood sugar in the normal range. The first-line strategy to achieve this is by improving dietary intake. Healthy, balanced diets are generally characterised as being high in dietary fibre and protein, which decrease both blood sugar levels and appetite. If blood sugar levels are reduced toward normal levels, the chances of having T2D-related complications are reduced. Likewise, if appetite is decreased, intake of energy-rich foods will likely also decrease, helping to reduce body weight, which is a key risk factor for T2D. However, an ongoing problem with healthy diets is that they are not suitable for all cultures and most of the research around them has been conducted in people of European origin, therefore not being applicable to South Asians. Furthermore, people often find it difficult to stick to these diets.

Figure 1: Prevalence of diabetes in England by minority ethnic group and sex. Diabetes is more prevalent in people of south Asian descent (red boxes) compared with men in the general population (blue box).

The potential solution

One food that is high in both dietary fibre and protein is mycoprotein. Mycoprotein is the name given to the biomass of a fungus called Fusarium venenatum. Mycoprotein is low in fat and calories and high in both dietary fibre and protein.

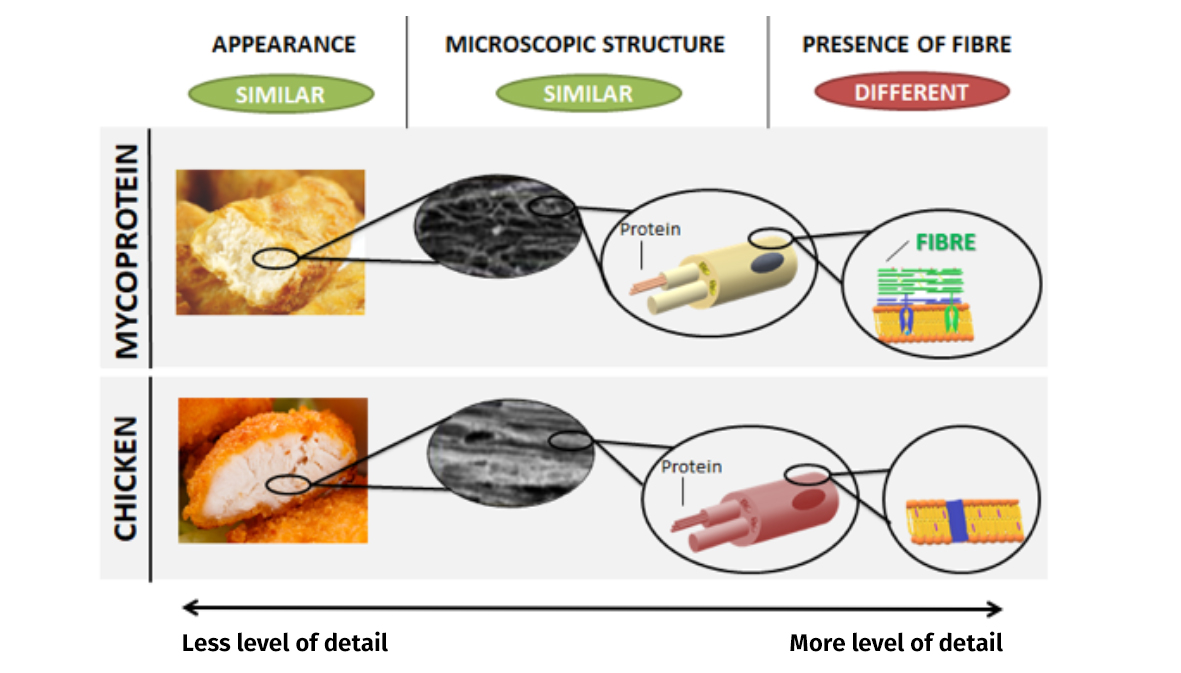

Mycoprotein is commercially available across Europe, North America and Asia under the brand name of “Quorn”, which makes it suitable and accessible to many cultures. In addition, mycoprotein’s appearance and texture has been shown to be very similar to animal-derived meat as both microscopic structures are very similar, with the exception that mycoprotein’s structure is surrounded by fibre (Figure 2). Professor Gary Frost, head of the Nutrition Section at Imperial, said: “Mycoprotein has a unique food matrix called hyphae, which may act as a barrier for sugar absorption during digestion, therefore improving sugar levels in blood.”

Since mycoprotein is high in both dietary fibre and protein, suitable for all cultures, widely available and has a similar taste to meat, we believe that it could be an effective food for regulating blood sugar levels and appetite in people with T2D.

Figure 2: This figure illustrates the similarities and differences between mycoprotein (at the top) and chicken (at the bottom) when you zoom in at different levels of detail.

The question

We have previously shown that mycoprotein has a positive effect on blood sugar levels and appetite in healthy overweight and obese people who do not have T2D, but little is known about this effect in people with T2D from South Asian and European ancestry. It is for this reason that we are investigating whether mycoprotein alone, or in combination with another fibre called guar gum, is able to reduce blood sugar levels and appetite in both ethnic groups. Professor Gary Frost added: “Instead of testing a sole food, we are testing what a usual meal would be, such as mince mycoprotein with rice accompanied by a chapatti bread. This bread has guar gum incorporated into the dough. We think that, by combining both types of fibre (mycoprotein and guar gum), an additive effect in lowering blood sugar levels could occur in people with T2D, regardless of their ethnicity.”

Why is this important?

This research will help us understand how blood sugar responses differ between people of South Asian and European descent with T2D, and will also highlight the importance of tailoring diets according to cultural background. This is important because diet is a cheaper tool to manage blood sugar than diabetic drugs and could, therefore, be of great benefit to health care systems, especially those based in lower-income regions found in parts of South Asia.

Can you contribute to this research?

Yes you can! The Nutrition Section is currently looking for volunteers for a nutritional research study looking at the effect of mycoprotein on blood sugar levels and appetite in people of South Asian and European descent with T2D. To be suitable to participate, you have to have T2D, not be tak

ing insulin and be from either South Asian (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, India, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka) or European ancestry. Participants will be asked to attend the Imperial Clinical Research Facility at Hammersmith Hospital for six separate study visits, which are five hours long approximately, during which you will be asked to consume a meal within 15 minutes, have blood taken and consume a buffet meal. Expenses will be paid. If interested, please contact protein@imperial.ac.uk or call 07522887666.

Anna Cherta-Murillo is a PhD Student at the Section of Nutrition in the Department of Medicine at Imperial College London.

This post has been adapted from a submission to the Graduate School 4Cs Science Communication Competition.

Lead image credit: Shutterstock 1124737562

Following the launch of the Faculty of Medicine’s reorganised academic structure on 1 August 2019, this post was recategorised to Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction.