Historian of medicine Dr Jennifer Wallis explores some of the parallels between 19th-century health concerns and the current pandemic, and introduces us to one of her favourite Victorian objects.

I spent most of Sunday afternoon sewing face masks out of old t-shirts, pretty inexpertly and with more than a few pricked fingers. In a recent article for the BMJ, Professor Trisha Greenhalgh and colleagues argue for the precautionary principle when it comes to mask-wearing during the COVID-19 crisis. They argue that ‘we have little to lose and potentially something to gain’ from wearing masks. A quick Google search for news items about masks yields a constantly growing number of results and questions: Who should be wearing masks and where? What should masks be made of? Can/should masks be fashion items?

Masking Victorian-style

Masks are the topic du jour but the debates surrounding them are oddly familiar. I’ve been thinking about face masks for some time – not their modern uses, but their historical incarnations. As a historian of nineteenth-century science and medicine, I’ve long been intrigued by the devices and products marketed to health-conscious Victorian consumers, from bronchitis kettles to ‘Pink Pills for pale complexions’. For the last few years, I’ve been particularly distracted by the respirator – a device designed to protect the wearer from inhaling hazardous atmospheres.

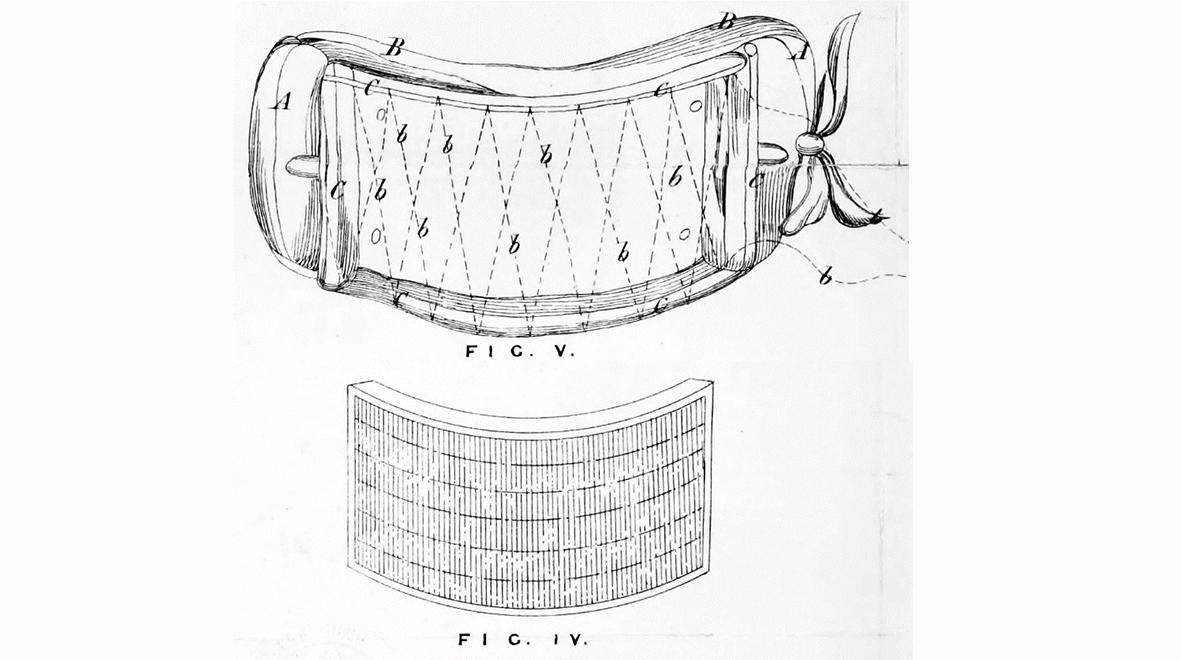

The respirator was patented in 1836 by a British surgeon, Julius Jeffreys. After the death of his sister from tuberculosis (TB), Jeffreys wanted to design a product that would offer protection to those suffering from TB, asthma, and other respiratory conditions. The respirator, as Jeffreys described it, was ‘an apparatus to abstract the heat from the breath … and thus warm the air’. The main part of the device, placed over the mouth, was made up of a series of thin metal plates. These were covered in black cloth and the respirator was kept in place with elastic ties around the head. Like many doctors of his time, Jeffreys was not necessarily concerned with the risk of infection – that would come later in the century – but with the effect of cold air on the lungs.

Jeffreys recognized these aesthetic challenges early on. Later designs tried to make the respirator less conspicuous, using beige-coloured cloth or concealing it within a scarf. Other entrepreneurial medical men were quick to jump on the bandwagon, with a number of patents that hoped to improve upon Jeffreys’ model, reducing the size or changing the colour. Some added pockets for filters made of charcoal or medicated cotton wool. Lennox Browne, a doctor at the Central London Throat and Ear Hospital, designed my personal favourite: a rather chic ‘respirator veil’ for ladies, which was available to buy at London department store Marshall and Snelgrove.

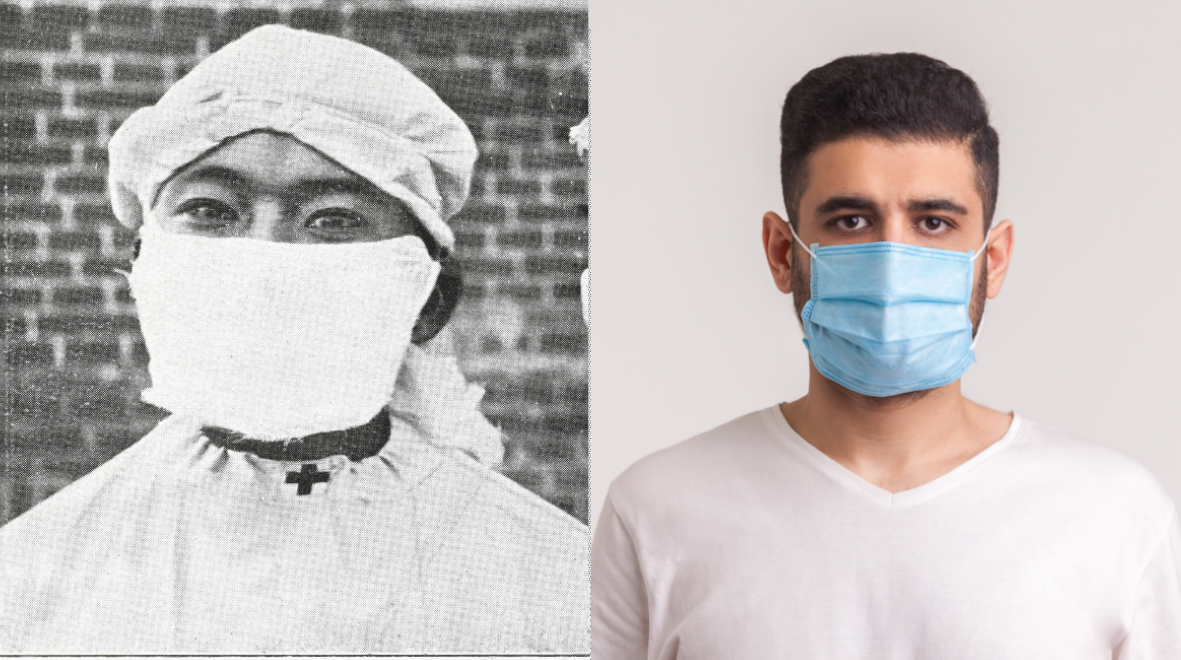

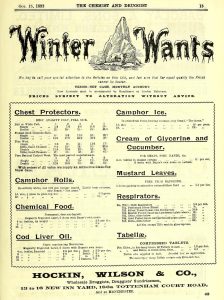

The respirator was not, in its early years, a cheap disposable item. Jeffrey’s respirators ranged from 7 shillings for a basic device (about £20 today), to 50 shillings (c.£140) for a gold-plated model. For those who couldn’t afford a ready-made respirator, there were other options. Popular magazines including The Girl’s Own Paper printed instructions for crochet respirators. The same enterprising spirit would be demonstrated on a larger scale during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. As the historian Nancy Tomes has explored, some people made masks from delicate chiffon, others repurposed handkerchiefs. In the COVID-19 era, suggested materials for homemade masks span from old t-shirts to tablecloths to pillowcases, while fashion brands such as Burberry are switching their production lines to manufacturing masks.

Communication barriers

Whether made from a well-loved t-shirt or the lurid floral pillowcase you’d forgotten about, face masks can pose significant barriers to communication – for those who lip-read, for example. The Victorian respirator had similar downsides. Compared to the fabric face mask, the respirator was very constricting: its snug fit restricted the movement of the mouth and lips. This was a problem for many users who felt they were protecting their health at the expense of sacrificing social interaction. Martha Sherman, a London minster’s wife writing in the 1840s, was frustrated that her respirator stopped her speaking to the people she met during her charity work: ‘I thought how humbling it was to be literally disabled by my respirator from speaking to any of the poor I met.’ The writer Jane Welsh Carlyle was more positive, describing the respirator as making all the air she breathed in feel ‘as warm as summer air’.

The respirator could change the wearer’s relationship with the environment, then, but also their relationship with others. For the sufferer of TB or asthma, the respirator could be both liberating and limiting. It allowed them to be in public space without fear of worsening their condition, but it removed the possibility of conversation with others.

From the 19th century to COVID-19

Many of the issues that we are currently grappling with in relation to masks are not novel, although the reasons for wearing masks may be. In 1836 Jeffreys was optimistic that the respirator might become as unremarkable as a pair of glasses. Although his invention didn’t become quite so common, the face mask has already become an ‘unremarkable’ sight for many of us. In coming to terms with our ‘new normal’, I find some reassurance in the accounts of those who struggled with similar issues in years gone by.

Masks can be experienced in different ways, both positive and negative – often at the same time. Not everyone was convinced of the usefulness of the respirator in the nineteenth century, but many people chose to wear it, even as late as the 1890s. For many users the safer participation in public life that it facilitated, the sense of security it gave both to them and others, was invaluable. Respirators could be re-designed, modified, or home-made, depending on the wearer’s individual needs and resources. Greenhalgh and colleagues note in their article that people should be supported to change their behaviour should they so wish, regardless of the proven efficacy of masks. Many Victorian advocates of the respirator would have agreed.

Dr Jennifer Wallis (@harbottlestores) is a Medical Humanities Teaching Fellow at the Faculty of Medicine, and Lecturer in the History of Science and Medicine at the Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication (CLCC).

Lead image adapted from Wellcome Collection and Shutterstock.