Four Imperial researchers recount their experiences of volunteering at one of the mega-labs built to scale up COVID-19 testing in the UK.

Since March, the UK Biocentre laboratories located in Milton Keynes has become one of four Lighthouse Labs (the others are in Glasgow, Alderley Park in Cheshire and Cambridge) – the largest network of diagnostic testing facilities in British history. Every day the team process and analyse around 30,000 swab samples from across the country to test for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. They use a combination of manual processing and high-throughput robots to inactivate the viral samples, extract the RNA and analyse them with a technique known as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to detect the presence of the virus.

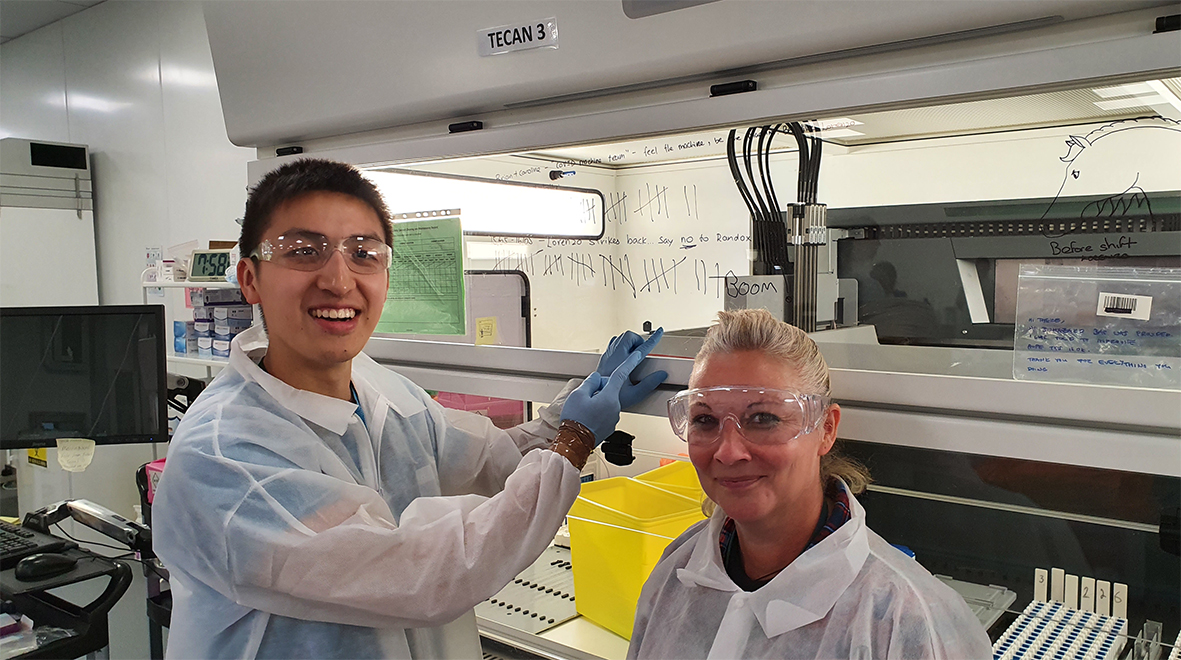

The UK Biocentre labs were uniquely placed to help in the testing efforts, as in normal life they are usually home to around 30 staff processing and archiving clinical samples from hospitals around the UK. 200 volunteers across academia, civil service and industry answered a call to support with COVID-19 testing, including several PhD students and postdocs from Imperial. As their secondments draw to a close, we speak to some of the volunteers to hear about their experience:

Dr Stephanie Ascough is a postdoctoral research associate at the Department of Infectious Diseases.

As soon as the call went out for volunteers to help with COVID-19 testing, I signed up. Within a week I heard back from the NIHR UK Biocentre in Milton Keynes. Shortly after this, in mid-April I found myself driving up an almost deserted M1, past signs reminding us to ‘Stay home, Save lives’ and restrict ourselves to ‘Essential travel only’.

The extent of the Coronavirus pandemic required a massive scaling up of operations at the lab, with almost 200 volunteer research scientists recruited to work 12-hour shifts around the clock. The enormous amount of work also involved building and outfitting a brand-new sample processing lab, larger than any single lab I’ve ever worked in. This, along with the existing UK Biocentre labs, has been filled with Microbiological Safety Cabinets (MSC), qPCR instruments and KingFisher RNA extraction instruments, all generously donated by academic labs from around the UK (including our own at Imperial).

Every procedure is double-checked using a ‘buddy system’ to ensure compliance. In practice, this means we work in teams of two, with one individual collecting the sealed specimen transport bag and registering the unique identifying barcode on the bag and specimen tube containing the nasopharyngeal swab, on a computer system. This is then transferred to the scientist working in the MSC, who opens the sealed outer and inner bags and then the specimen tube, the viral transport medium within is pipetted into an allocated well of a 96-well plate, containing lysis buffer to inactivate the virus. All of which is witnessed by the second individual, with documentation at every stage.

The plate of inactivated virus is then taken to the KingFisher automated extraction instruments, and after a number of wash steps, familiar to anyone who has extracted RNA, the viral RNA is eluted into plates ready for the final steps, which involve the addition of the RNA along with PCR reagents to a qPCR plate by the automated Tecan PCR workstations. The genomic material is then amplified on one of 40 qPCR machines, to detect the presence of the virus. All of which means a result can be generated in less than 12 hours from arrival of the swab at Milton Keynes.

In addition to the manual inactivation of the virus, I have spent quite a few shifts working with the high-throughput lysis Tecans. Along with the automated RNA exaction instruments and PCR Tecan workstations, these automated processes have allowed the UK Biocentre to exponentially increase the number of samples which can be processed every day (plus the robots are so satisfying to operate!). I feel lucky that my background in the Department of Infectious Disease at Imperial has left me comfortable working with clinical respiratory samples from influenza and RSV infected individuals, so all the biosafety and PPE requirements were second nature to me.

Although, I don’t think any of us were quite prepared for the massive scale of the testing program; swabs are delivered constantly throughout the day and night by Royal Mail trucks and the lab is operating 24/7. The atmosphere has been amazing though, despite our team working from 8pm to 8am, the scientists are cheerful and determined. As is common with researchers in any lab, we’ve named all our equipment, with personal favourites being the PCR Tecan workstations named after the 5 Spice Girls, the KingFisher with the asset number KF007 (James Bond, obviously) and the lysis Tecan named ‘Florence the Machine’!

Find out more about Steph’s experience.

Brian Leung, Microbiology PhD student at the Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction

I am part of a team of volunteers (around 200 across academia, civil service and industry) that answered the call to bring our daily expertise as biologists to help run the lab side of swab testing. We are based at the UK Biocentre at Milton Keynes and currently staffed 24/7 to ensure that testing capacity is met. As I write this, it is week 5 of night shifts for myself!

The buzz and atmosphere among the team and within the lab keep us going all night long. It has been a privilege working alongside a diverse group of scientists and will definitely keep in touch with everyone. Anyone with good ideas can contribute to the procedures we use in the lab and we have anyone from undergraduates to PI’s (principal investigators that would normally run their own research group) running side by side. I have pretty much experienced the full gamut of the sample testing workflow here at the UK Biocentre: manual processing samples, automated sample processing (Tecan robots), Kingfisher automated RNA extraction and qPCR plate preparation (Tecan robots).

Where there is a will and leadership, science can bridge the gap between everyone. It’s been a very different experience from the academic research experience and gives a very appreciative insight to what biomedical scientists in the NHS have had to do before we stepped in to do a large amount of PCR testing. I have also made many friends that I will be keeping in touch with, many of them outside the field of microbiology!

During my break at last night's shift at @LhouseLabsUK, I took the opportunity to visit our qPCR team and found qPCR machines generously loaned from my parent institute @ImperialInfect @ImperialSci @ImperialMed. And yes the room sounds like this 24/7! #science pic.twitter.com/VW9OJv4mX8

— Brian Leung (@bleung_tri) May 11, 2020

Akshay Sabnis, PhD student at The MRC Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection (CMBI)

It has been absolutely incredible to be a small part of this amazing and vital project. The sheer scale of the laboratory is what has surprised me the most – we have dozens of the most advanced liquid handling robots and it’s been an immense effort to get the lab capable of processing so many samples everyday – we even had the army involved at the start. It’s been brilliant working with some of the best scientists in the country – all from extremely diverse backgrounds. One day you might be working with a Principal Investigator, and the next day with a postgraduate physicist. Despite this, the teamwork has been fantastic – everyone works together with no ego all for a common goal of trying to make this incredibly difficult time a little easier for all of us. It’s been busy, intense and tiring with long shifts requiring constant concentration but an awesome experience thanks to the wonderful people I’ve been lucky enough to work with.

The biggest difference is realizing that you are one part of a much larger process. Whilst in my PhD, you generally will complete an experiment from the beginning to the end – here, we are each assigned a specific task along the sample processing pipeline which when completed is handed on to the next stage. In many ways, it feels like working in a factory. The work is intense, in that it requires a combination of concentration and speed – we want to process as many samples as possible, but also ensure that they are all perfect which brings a unique pressure that is very different from my day-to-day work at Imperial. And of course, I never have to do 12-hour night shifts during my PhD!

I have learned an incredible amount in the few months since I’ve started. From a technical point of view, the incredible attention to detail when carrying out diagnostic work was eye-opening. Furthermore, it’s been incredible to see what’s involved in such a high-throughput process, hopefully we can use some of this knowledge to optimize processes in my PhD! I have learned how to operate advanced robots and how to handle extremely dangerous viral samples in a safe manner. However, more importantly, I have learned how to work as part of a huge team. The biggest thing I’ll take away is a whole load of amazing new friends – my shift team has really become like a wonderful family and I’ll really miss everyone a lot when I return to Imperial.

Malgorzata Borkowska, postdoctoral research associate at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences

I was responsible for extracting the viral genetic material from patient’s samples (nasal or throat swabs), which requires preparation of the reagents that are used for the reverse-transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) and combining those with the RNA obtained from the patient’s samples. This procedure is highly automated which enables us to test many samples in a relatively short period of time.

It has been an interesting 2 months! The laboratory is operational 24/7, with four teams of scientists working back to back 12h shifts, 3-4 days a week. Long hours and busy days are quite common in academia, but when you run around between robots, train new volunteers, coordinate with other sections so to have the testing process running smoothly and at maximum capacity… at the end of your shift you are exhausted!

On top of that, the team that I was a part of started with 4 weeks of night shifts, which for me, a morning person; was very tough to get used to. I am still amazed that I’ve survived those, and still kept my obligation to my group at the MRC LMS. Nevertheless, working with a fantastic team of people from all over the country and helping out as much as I could made all those long hours worth it. I’ve learnt that with the right group of people, nothing is impossible.

The UK Biocentre Lighthouse lab is like an organism, with all sections relying on each other for smooth and efficient operation. At the MRC LMS, as a postdoc, I am more reliant on myself when it comes to running my projects. But I think the biggest difference is strict adherence to the standard operating procedures. I am very much used to troubleshooting and optimising a protocol before committing to it. At the testing centre, we were specifically asked to follow the procedure to the dot, even if we saw ways how to improve it (at least in our eyes).