Justine is a participant in Imperial’s COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial – here she discusses how the trial is progressing.

“Am I immune?” “Could I be immune?”

These are questions that have been unavoidably circling in my head ever since I received an experimental coronavirus vaccine as part of a clinical trial led by Imperial College London.

Every time I exercise, take public transport, do my weekly food shop, socialise with those close to me, I’ve been trying to quash this invisible shield that part of my brain believes might be there, shrugging off any potential encounters with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

I didn’t enter this trial so that I’d get a free pass to behave irresponsibly in the midst of a pandemic, which is frighteningly rearing its ugly head again in my home country. I always knew that immunity was never a certainty, having never been tested in human beings before. I was more confident that it wasn’t a dangerous thing for me to do, and certain that it was a good thing to do.

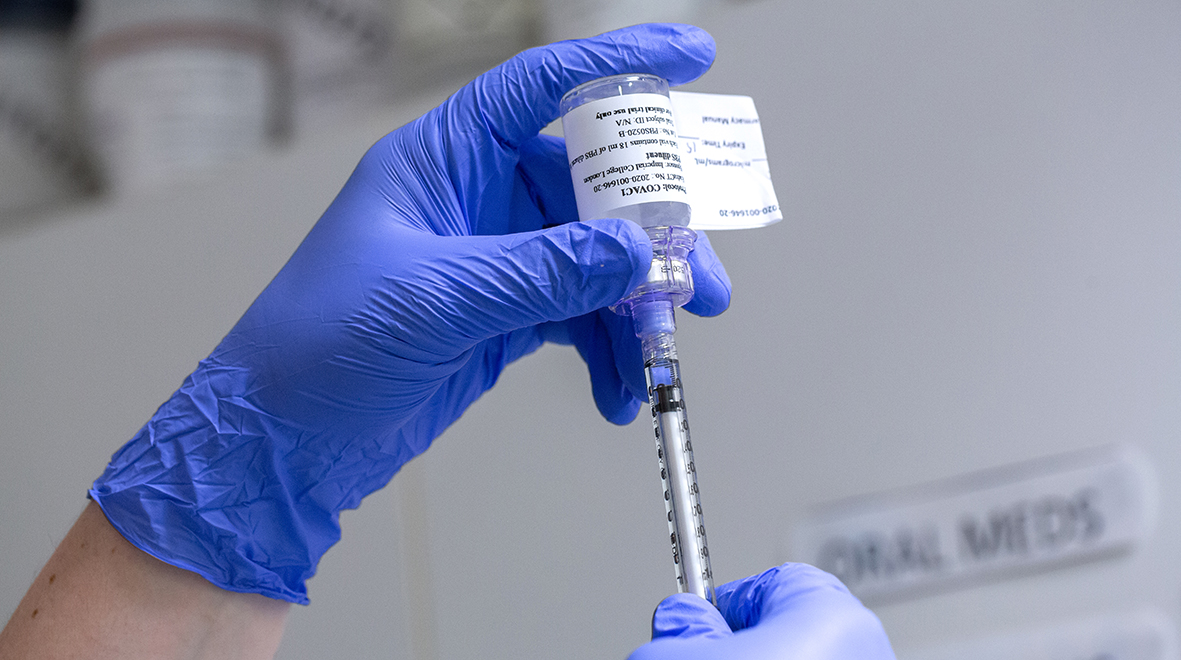

And by participating, I have certainly helped to prove both of these latter points. I’ve had two shots of the vaccine, which works by instructing my cells to make fragments of the coronavirus, thereby prompting my immune system to react and, hopefully, keep a protective memory of the threat. I’ve had no side effects at all; not even a sore arm. The devil on my shoulder sort of wished for even a little redness where the needle went in, that I could wear proudly as a mark of my contribution to research.

Alas, though, everything has been very placid and uneventful, which is a good sign that I’m thankful for. And my experience – and that of fellow participants – has built important evidence that this vaccine is very safe. “Well-tolerated” is the technical term I read in a letter I received during my 8th visit to the trial centre.

As my eyes crisscrossed down the page, I initially felt my heart sink a little. Everything in the letter about the trial’s progress was encouraging, although I couldn’t help but focus on the point that at the highest dose trialled so far, participants’ immune responses may not be as strong as was hoped. Although the team tells me that the dose I received could still be protective, they say they would have more confidence if the responses were higher with higher doses. So the trial will continue, now recruiting a new group of individuals to test different doses, in the hope of stirring the immune system into more rigorous action.

My invisible bubble of feigned immunity popped. It’s probably for the best.

Finding a coronavirus vaccine: it’s not a race

As participants, we have all given a lot to the trial; time, effort, blood – around 70 test tubes, each, to be precise. But not as much as the trial team, who have been working tirelessly since the early days of the pandemic to bring forward a technology that could be a game-changer in the fight against COVID-19.

So of course I wanted this vaccine’s journey to be a straight Roman road to success, rather than the traditional windy path of research. Not for selfish reasons, but because we all so desperately – even if credulously – seek a silver bullet to end this wretched disease.

But this is how trials work. During the early stages of any new medicine’s development, researchers need to find out whether it’s safe, and also work out the best dose to use. So the exploration of new doses is standard procedure. Getting the dose spot on first time with an experimental drug would be remarkable. The fact that this vaccine has come this far in such a condensed timeframe is, however, pretty remarkable. And the team has told me that although the immune response might not be strong enough yet, they’ve seen promising signs that stronger doses produce bigger reactions.

“This is a new technology,” Professor Robin Shattock, who developed the vaccine, told me. “So we need to make sure we get it right, rather than rushing to be first.”

Testing times continue

Outside of COVID-19, we would not consider it a bump in the road that scientists are playing by the regulations and protocols that are there to protect people. We would be lauding them for putting safety before speed. And that’s what we should do now.

“Now that we have established that our vaccine has a good safety profile, and we’ve seen a clear ‘dose-response’, we want to maximise its potential by exploring additional doses,” said Prof Shattock.

“This is a pioneering technology. It’s scalable, easier to manufacture than many others, and we believe it can be given multiple times – as many times as necessary.”

That’s a really important point, I learn, because it’s widely believed that no vaccine can offer a lifetime of immunity from a single shot. So giving the immune system friendly reminders in the form of boosters can enhance the chance that immunity will be long-lasting.

So although the trial has been pushed back slightly, it’s still on track, and should be considered as a sign of scientific integrity. There is a tale of a tortoise and a hare that seems particularly poignant today. And I share the team’s cautious optimism for the future.

While Justine works at Imperial College London, all views expressed here are her own. She went through the same application and selection processes as all other participants on the trial.

Very encouraging – so far.

If immunity fades over time, it looks as if the cells which were producing the alien protein die rather than divide and pass on this ability. Is this known?