As Lauren Headley-Morris nears the end of her PhD, she reflects on the experience gained and why learning won’t stop after she’s completed her terminal degree.

Terminal is a weird word. Usually heard on TV associated with cancer, you wouldn’t necessarily want a degree that is terminal. Some days I think my PhD is the best thing since the sequencing of the human genome; other days I think it might be the death of my love of science. But terminal is used in some less, erm, disastrous, melodramatic? scary? ways.

One of these less-morbid settings is travel. A PhD is, by nature, the end of the line of academic qualifications. It doesn’t mean you’ve now mastered your subject, sadly. There are post-doc positions and even professorships in the future perhaps.

I’m a third-year, Asthma UK funded, Clinical Medical Research PhD student based at the Guy Scadding Building, Royal Brompton campus. My work is focused on transcriptional regulation in asthma. While my day to day is obsessing about microRNA and things that are too tiny to see, I think it’s important to take a second now and then to sit back and reflect on the bigger picture of where my PhD fits in with my life as a whole. Maybe it’s the effect of spending so much time in isolation or maybe, coming to the end of my formal academic training, I’m getting a little philosophical.

Completing a PhD is understandably a huge undertaking for any individual. In committing to a terminal degree you have chosen to pursue studies in an area of interest beyond what is in the textbooks. You wouldn’t be in the position if you didn’t demonstrate the ability technically or mentally to manage it, but that doesn’t make the task any easier. Your place has been decided by committees of Doctorates and Professors who have not only been through it themselves but have watched and nurtured countless budding researchers to blossom into scientists that decide how to spend their own well-warranted grants, in their own labs.

While I often historically compared my own studies with other longer courses, like medicine, I thought that I had not performed to the same level that would get me into medical school, therefore it was a lesser challenge to complete a PhD. As a third-year, I can see that perhaps I was a bit too hard on myself. Don’t get me wrong, medicine, I’m sure is very challenging, but there is something about the lonely devotion to a topic in which you soon realise you are the most expert. While supervisors are highly skilled and experienced, the truth is, a PhD wouldn’t be such if the answers were already known.

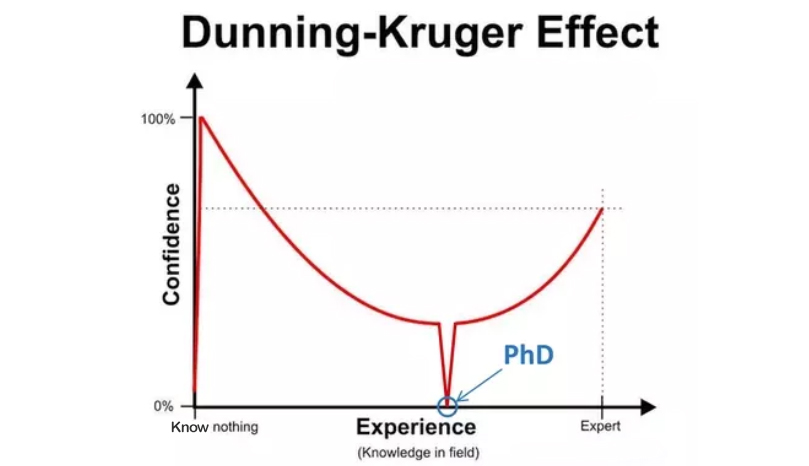

As I’ve already highlighted, although a PhD is technically the terminal level degree one can do in a subject, there is still more that can be learned. You will unlikely leave the sheltered wing of your supervisor ready to start your own lab, or with all the possible skills required for your area of research. New techniques and methods are developing all the time. There will be plenty more to learn. But what you should leave with is the tools to know how to develop that knowledge, how to prioritise tasks in the most efficient manner, and what things you don’t know that you’ll need to learn. This has on occasion given me some relief when I think I know nothing. The below figure highlights this point of the paradox of experience and confidence.

As such. There are some things I wish I had known or thought of regarding my survival (drama llama) through the process. Stuff that might seem obvious but I just hadn’t considered.

While many PhD candidates have experienced masters studies with projects that can end in less than ideal/or publication-worthy results, a PhD extends the torment or joy depending on your luck in a significant way (and I mean with a p < 0.0001). Us PhD students have the lucky position that in reality, our projects may well be the last time we can fail spectacularly and be rewarded for it*. So, you’ve got nothing to lose!

This message is a call to action. A PhD doesn’t have to feel terminal. It’s a chance to turn a new leaf of a chapter yet to be written.

For now, thank you for reading, and I raise my extra strong coffee to you, my fellow NHLI cohort, ”May all your experiments be successful and significant!”

*with the understanding that all the experiments were logically thought through etc… We’re not going to be testing if we can make knives from poop. That’s silly… Oh snap (Eren et al. 2019)

Lauren Headley-Morris is PhD student at the National Heart and Lung Institute and is funded by Asthma UK.

Complete our survey

The NHLI postgraduate student committee is compiling a series of PhD hacks to make the journey easier. If you have any questions you’d love to ask but were too scared to ask, please email the NHLI postgraduate committee. If this has inspired you or reminded you of some tips you learned during your PhD studies, fill in our survey and we’ll include it in our series. All the questions and tips we receive will be anonymised before we compile the series. Unless you want a shout out (winky face)!

Complete the survey