What happens when industrial technology meets nature? A French invention of the 1830s, the compressed air bath capitalised on the allure of ‘pure countryside air’ to treat a range of respiratory problems. Dr Jennifer Wallis, Medical Humanities Teaching Fellow, explores the fascinating history of these baths and their therapeutic uses in mid-Victorian Britain.

During the summer holiday season, many of us will have taken a break to recharge our batteries. Whether it’s gazing out over a clear blue sea or hiking through a forest, connecting with nature is often a key component of our holidays.

Tourists in the 19th century sought a similar experience. They yearned to escape the crowded city or the routines of home to immerse themselves in a new environment. The era is most associated with the seaside resort, which grew in popularity as the railway network expanded. But many Britons were also choosing to follow in the footsteps of their eighteenth-century ancestors by visiting spa towns like Malvern. Spa towns were renowned for their health benefits, from the freshness of the air to the energising effect of the mineral waters. Hotels and resorts sprung up in spa towns to cater for the health-seeking hordes.

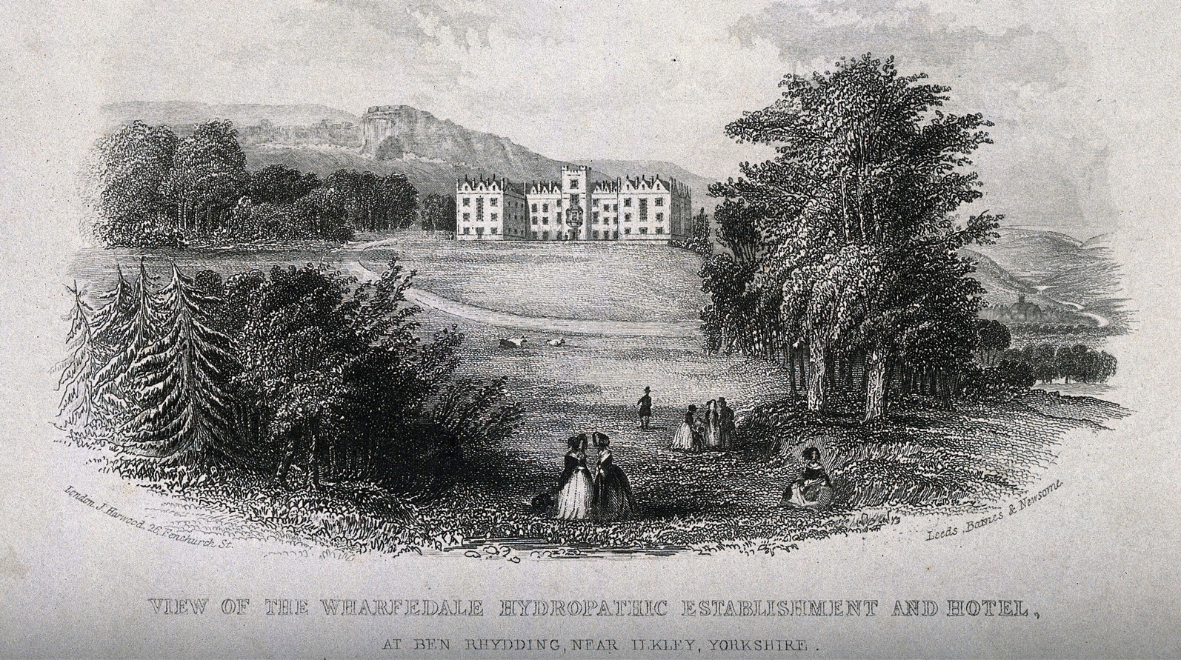

One such resort was the Ben Rhydding Hydropathic Establishment in Ilkley, Yorkshire. It cashed in on a contemporary interest in hydropathy, a treatment regime based on baths and showers. Ben Rhydding offered its visitors a variety of activities to supplement these treatments: bowling greens, dances, and guided walks of local beauty spots. It also offered a rather unusual experience for the health-seeking tourist, one that used air rather than water: a compressed air bath.

Medical Use of Oxygen

Compressed air was widely used in the construction of bridges and tunnels in the 19th century. This gave doctors ample opportunities to observe its effects. As well as troublesome symptoms such as breathlessness, many doctors noticed the positive impact of compressed air on conditions like emphysema, a chronic lung condition that causes breathlessness.

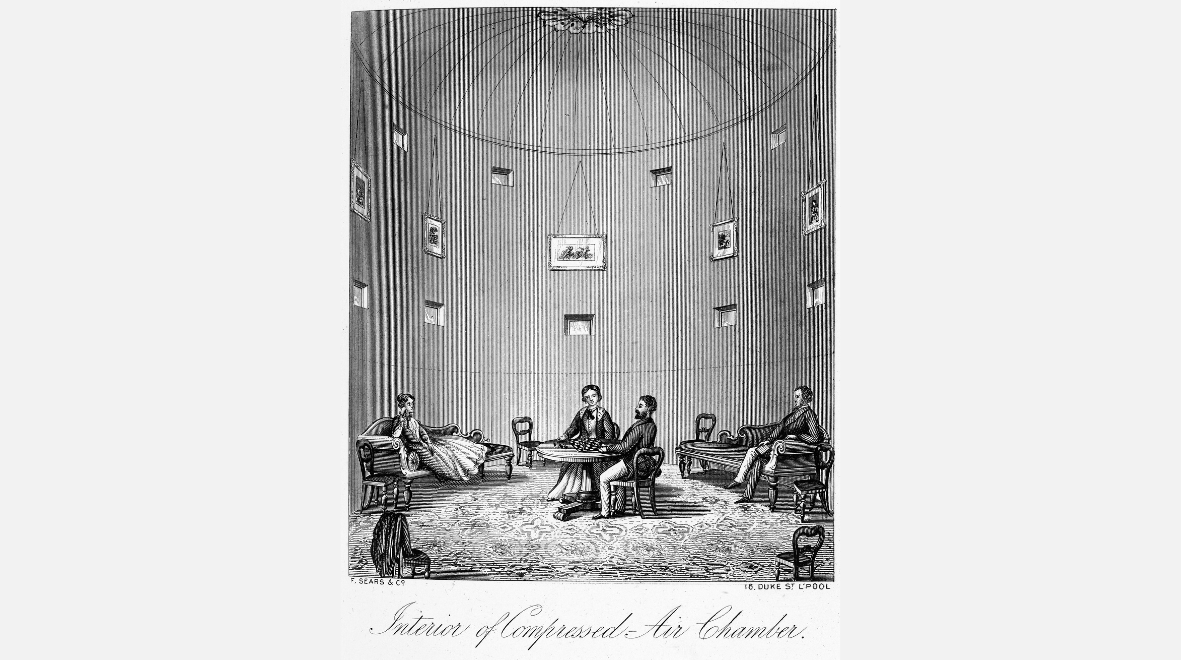

The first compressed air bath was likely made by a French engineer in the 1830s. It was a formidable-looking piece of equipment. Made of iron plates with an airtight door and porthole windows, it looked like something from a factory rather than a health resort. Visitors would sit inside for around two hours as compressed air was forced through small holes in the floor. To make the experience as comfortable as possible, the bath was furnished with carpets, tables, and chairs.

The medical theory behind the bath was that compressed air would force a greater amount of oxygen into the body than was available in the normal atmosphere. Oxygen had already proven helpful in wound healing, so its medical applications were being eagerly investigated. The pressure used in the bath was between half and two-thirds of an atmosphere with a pressurisation rate of 1lb every three minutes. This falls within modern-day accepted safe limits for hyperbaric medicine (the medical use of oxygen). The bath was recommended for respiratory problems such as asthma, although some more enthusiastic advocates claimed that its powers extended to the cure of deafness and menstrual problems.

Ben Rhydding’s bath was not an isolated example. My research has found at least 50 baths across Europe and America by the 1880s. These were mostly at health resorts. However, a bath also existed at Brompton Consumption Hospital where it was used in the treatment of tuberculosis (TB).

‘Extra-strength’ fresh air

The compressed air bath could perhaps be dismissed as just another quirky 19th-century invention (of which there were many!). But what I find fascinating about the bath is how it brought together modern industrial technology and nature. It wasn’t enough to simply pump any air into the machine. Doctors were clear that baths should use the ‘good air’ of the countryside. Placing a compressed air bath in a spa town meant that users received an ‘extra strength’ version of the fresh air outside. Some baths allowed users to enjoy the natural landscape while simultaneously reaping the benefits of the technology. Dr Joannis Milliet boasted that his compressed air baths in Lyons allowed patients to gaze out over the Alps. Rather than being separate from nature, the compressed air bath was a technology that relied upon it.

So, what happened to the compressed air bath? Like other resorts in the late 19th century, Ben Rhydding expanded its horizons as holidaymakers demanded a wider range of amusements. After adding a golf course to the site in the 1880s, the resort’s owners decided to turn it into a golf hotel. Brompton Hospital’s bath, however, was still in use in the 1920s. The collection of metal for the war effort during WWII likely put an end to those baths that remained in operation.

Compressed air remains a vital part of modern medicine, used in ventilators and incubators for example. Our experiences with it, though, are generally more discrete than the compressed air bath. As we’ve seen, the compressed air bath melded technology and environment on a grand scale in an attempt to resolve individual health complaints. It was based on the most up-to-date medical knowledge at the time. Far from being simply a curiosity or a defunct medical technology, the compressed air bath is part of the history of technology and medicine. It’s an intriguing example of how we make technology available, and more palatable, to users. So, if you happen to have spotted a huge metal chamber lurking in a hospital basement, please let me know. I’d love to see one in person!

Dr Jennifer Wallis is a historian of medicine and psychiatry, and teaches on the BSc in Humanities, Philosophy and Law. She regularly works with colleagues across the Faculty of Medicine to incorporate the medical humanities into clinical teaching and training.