As the leading cause of heart failure in young individuals, dilated cardiomyopathy presents a unique set of challenges and implications. It is an intrinsic heart muscle disease that is the most common reason for needing a heart transplant. The origins of this condition are diverse, spanning genetic predispositions, external triggers that subject the heart to undue stress, or often, a combination of both. Dr Brian Halliday, a Clinical Senior Lecturer and British Heart Foundation Intermediate Fellow at the National Heart and Lung Institute sheds light on this disease and how medical advancements have enabled some patients to go into remission.

Heart failure can be a devastating diagnosis. The prognosis has been shown to be worse than many of the most common cancers. The words themselves often create a sense of doom for patients.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common cause of heart failure in young people and the most common reason to need a heart transplant. It is an intrinsic heart muscle problem where the heart becomes baggy and weak. It may be due to genetic susceptibility, extrinsic acquired triggers that put the heart under stress, or a combination of the two. At the National Heart and Lung Institute, we have a particular interest in dilated cardiomyopathy.

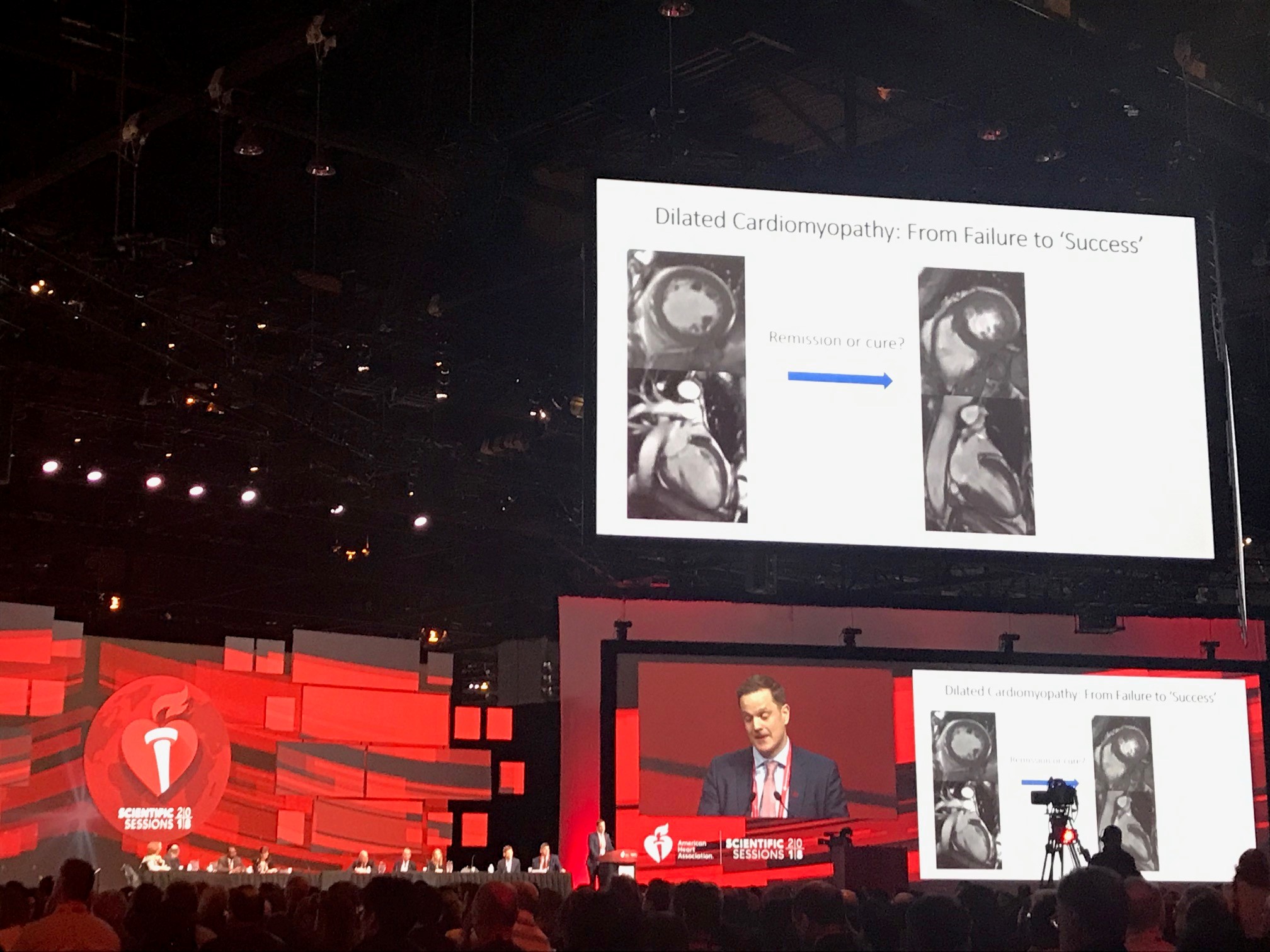

It’s not all doom and gloom though. Over the last 30 years, we have made tremendous advances in treating heart failure. Treating a typical 55-year-old patient with comprehensive medical therapy will add an average of 6 years to their lives. The news is even better for many patients with dilated cardiomyopathy who have a greater chance of responding to therapy compared to those with other forms of heart failure. Work from Dr Dan Hammersley, a research fellow at NHLI, and Professor Sanjay Prasad has shown that around two thirds of patients with newly diagnosed dilated cardiomyopathy will have significant improvements in their heart function in the first year after diagnosis. Many will go on to have complete resolution of their symptoms and their heart function may return to normal. This is one of the most satisfying bits of the job!

It has not been clear whether this degree of improvement represents complete recovery from cardiomyopathy or whether this simply reflects a form of ‘heart failure remission’. Patients often return to clinic and ask whether they need to continue all or any of their medications. They often feel back to normal and are worried about the impact or risk of side effects. Taking medications may reduce their overall quality of life and they frequently want to stop medications.

A few years ago, we set out to try to answer some of these questions in the TRED-HF trial. It was designed as a small trial to get the ball rolling. We studied 50 patients previously diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy, all of whom experienced complete improvement in cardiac function and resolution of symptoms. Half of patients stopped their medication in a gradual fashion and the other half continued them. We expected to only see a small number of patients experience changes in their heart function. To our surprise, 40% of patients had a relapse of their cardiomyopathy after stopping therapy compared to none who stayed on therapy. I now suspect many more would have had a relapse if we had waited longer.

This small trial answered our initial question more emphatically than we expected. It confirmed that the majority of these patients have a form of heart failure remission and typically require some medications to maintain it. After the trial, our colleagues from the Patient Experience Research Centre interviewed participants to gather their perspectives. We also held some focus groups with patients and Cardiomyopathy UK, a wonderful charity that supports patients and their families. Patients told us not to stop here. They want more research investigating the types and amount of medication that best maintain heart failure remission. To steal analogies from the cancer world – a form of maintenance therapy, that not only minimises the risk of relapse but also side effects and impact on quality of life. This led to the birth of two more trials investigating the feasibility of tailoring the therapy required to maintain remission.

The work we have performed with patients has been so important. It has ensured we answer the best questions in the most appropriate way. I think doctors sometimes under-estimate the impact that taking medications has on our patients. It is easy for us to tell patients to take another medication in the hope that it might improve the numbers of scan reports. However, patients tell us that taking several medications every day for the rest of their life has a significant impact on wellbeing. Some describe it as a daily reminder of the cloud floating over the head that follows them around everywhere they go. They view being able to tailor their treatment regime once heart failure remission is achieved as a success.

Starting (and stopping) medications is a decision that should be shared by the patient and their doctor – each with uniquely important roles. The doctor providing expert insight into the possible risks and benefits of therapies, as well as any uncertainties. The patient then taking this information to make a decision by weighing it up in the context of their life and priorities for the future.

Management of heart failure remission will fortunately become a more common task in the future. I hope that our research will be able to help inform discussions between patients and clinicians about the best way to maintain heart failure remission.