In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), a notable number of individuals have smaller lungs for their sex, age, and height, especially in South and East Asia, as well as sub-Saharan Africa. The key question: Why does this pattern persist in these regions?

This phenomenon extends beyond physiological concerns, and as indicated by recent studies, reveals a troubling link between smaller lungs and heightened risks of suffering from heart disease and diabetes. Dr André Amaral, an epidemiologist at the National Heart and Lung Institute (NHLI), explores this phenomenon.

The BOLD study

Chronic lung diseases affect millions of people of all ages worldwide. Approximately 20 years ago, the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study was set up by Imperial College London to find out more about the prevalence and determinants of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which back then, was already considered a leading cause of disability and death.

The BOLD study was conducted in 41 sites across Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, the Caribbean and North America, and recruited more than 30,000 adults aged 40 years and over. The large coverage of world regions, and ethnic groups, as well as the large number of participants, all answering the same questions and undergoing the same measurements in a standardised manner, makes the BOLD study unique. Participants in this study provided information on several characteristics of their life. This included whether they had been diagnosed with lung disease, a heart disease, or diabetes, whether they smoke or ever smoked, their weight and height, and their highest level of education. The level of their lung function was measured through a medical test called spirometry, which measures how much air a person can breathe out in one forced breath.

The main findings of the BOLD study were:

- The proportion of adults with chronic airflow obstruction, a key characteristic of COPD, varies widely across the world but is slightly higher in individuals from high-income countries;

- The main determinants of chronic airflow obstruction are tobacco smoking, a low level of education and poverty, followed by a history of tuberculosis, a low body mass index and long-term exposure to dust in the workplace;

- The use of solid fuels for cooking and heating as well as outdoor particulate matter are unlikely to cause chronic airflow obstruction; and

- Chronic airflow obstruction can be predicted by measuring the function of the small airways earlier in life.

Unexpectedly, this study has also found that:

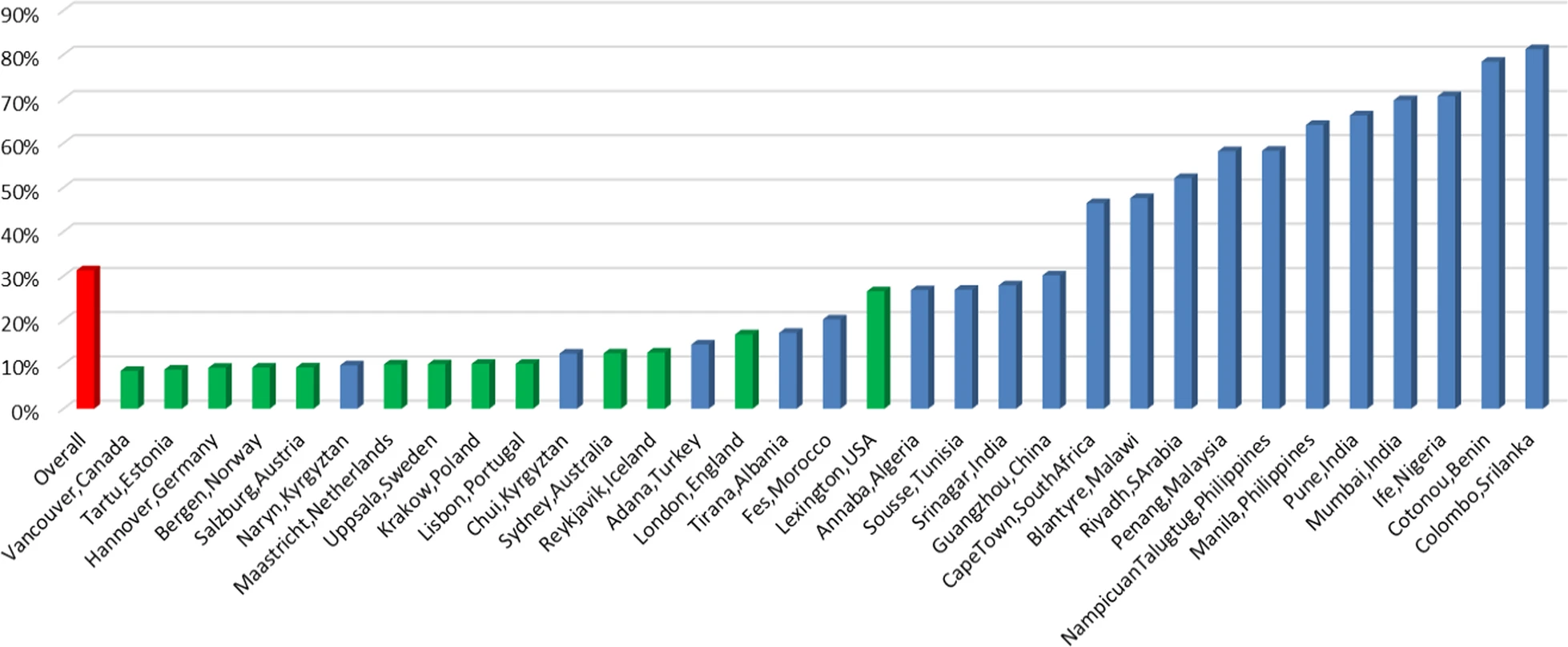

- There is a large proportion of people with small lungs, for their sex, age and height, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in South and East Asia, as well as sub-Saharan Africa, including countries where smoking is not common; and

- People with small lungs are more likely to have diseases of the heart or diabetes. The odds of having hypertension or cardiovascular disease were 50% higher among people with small lungs than among people with ‘normal’ sized lungs. The odds of having diabetes were 86% higher. These findings were independent of age, sex, body mass index, educational level, and whether they smoked.

Why do people in LMICs have smaller lungs and why are these people more likely to have cardiometabolic diseases?

The straightforward answer to these questions is, we do not know. Genetics partly explains ‘small lung syndrome’ but are other, non-genetic, causes. It is possible that poor lung development occurs during gestation or childhood, or both, which may also impact the development of other organs in the body. A diet poor in antioxidants and early life infections may also have something to do with this phenomenon. It is important to address this unmet need as having smaller lungs has also been linked to worse quality of life and reduced life expectancy even among people who have never smoked.

One of the aims of the research team I lead, is to know what causes individuals to have smaller lungs, as well as, why and how these people end up also having cardiometabolic diseases. I am also keen on exploring how this association varies between sexes and among individuals residing in rural and urban areas. I have been recently awarded an Academy of Medical Sciences grant to create a Network in Multimorbidity in sub-Saharan Africa to address the above questions. I am confident that through this work we will also find ways to better support and provide optimal care packages for those living with small lung syndrome.